Western Ghats (1342)

The Western Ghats is one of the largest Natural Heritage serial properties. It is a massive stretch of mountain ranges that includes several freshwater ecosystems. The mountain range extensively covers an area of 1000 miles, beginning from northwest to southwest of the Indian Peninsular along the west coast. There are three prominent gaps in the mountain ranges of Western Ghats, namely, the Palghat gap, the Goa gap and the Sencottah gap. These gaps divide the entire range of Western Ghats into three segments- Northern Western ghats, Central Western Ghats and Southern Western Ghats. This serial property comprises of a total of 39 component parts which fall under seven sub-clusters. These clusters are forest reserves and wildlife sanctuaries that are scattered in seven locations along the west coast of India. These are- Agumbe Forest Reserve, Pushpagiri Wildlife Sanctuary, Silent Valley National Park, Chinnar Wildlife Sanctuary, Eravikulam National Park, Achankovil Forest Division and Shendurney Wildlife Sanctuary. The Western Ghats hold immense significance as it is one of the last remaining stretches of the tropical wet evergreen rainforests in Peninsular India. It is regarded as a global biodiversity hotspot for being home to an exclusive radiation of endemic. Despite being a world heritage site and a remarkable junction of biodiversity, the site has been under tremendous pressure from anthropogenic-induced activities. Several factors have been considered as threats affecting the values and integrity of the property.

The Western Ghats is one of the largest Natural Heritage serial properties. It is a massive stretch of mountain ranges that includes several freshwater ecosystems. The mountain range extensively covers an area of 1000 miles, beginning from northwest to southwest of the Indian Peninsular along the west coast. There are three prominent gaps in the mountain ranges of Western Ghats, namely, the Palghat gap, the Goa gap and the Sencottah gap. These gaps divide the entire range of Western Ghats into three segments- Northern Western ghats, Central Western Ghats and Southern Western Ghats. This serial property comprises of a total of 39 component parts which fall under seven sub-clusters. These clusters are forest reserves and wildlife sanctuaries that are scattered in seven locations along the west coast of India. These are- Agumbe Forest Reserve, Pushpagiri Wildlife Sanctuary, Silent Valley National Park, Chinnar Wildlife Sanctuary, Eravikulam National Park, Achankovil Forest Division and Shendurney Wildlife Sanctuary. The Western Ghats hold immense significance as it is one of the last remaining stretches of the tropical wet evergreen rainforests in Peninsular India. It is regarded as a global biodiversity hotspot for being home to an exclusive radiation of endemic. Despite being a world heritage site and a remarkable junction of biodiversity, the site has been under tremendous pressure from anthropogenic-induced activities. Several factors have been considered as threats affecting the values and integrity of the property.

The Western Ghats hill range runs along west coast of southern India with latitudes 7° N to 21° N, and amalgamates with Sri Lanka to form one of the world’s 34 most significant biodiversity hotspots (Kumar et al. 2004). Geographically, this famous biogeographic region extends from 080 19’08”–210 16’24” N to 720 56’24”– 780 19’40” E with a north to south distance of 1490 km, covering a total area of 136,800 km2 (CEPF 2007). This range encompasses the states of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu. Three low-altitude gaps, namely, the Sencottah gap (8° – 9° N), the Palghat gap (10° – 11° N) and the Goa gap (14° – 15° N) distinctively divide the range into southern (8° – 11° N), central (12° – 15° N) and northern (16° – 21° N) Western Ghats (Robin et al. 2010; Bocxlaer et al. 2012). These three segments are characterized by specific geoclimatic factors such as annual rainfall, mean mountain height, relief features and dominant forest types (Ganesh et al. 2013).

The climatic condition of the Western ghats is described by heavy precipitation with unique monsoon patterns (Gadgil 1996). Monsoon season is during June – September and aids in regulation of the warm tropical climate (UNESCO whc.unesco.org; Champion & Seth 1968). The mean annual temperature falls in the range of 20 – 35°C in the day and 15 – 20°C in the night (Champion & Seth 1968). The presence of mountain ranges influences the regional climate, hydrology and the distribution of vegetation types and endemic floral diversity (Gadgil & Meher-Homji 1990; Das et al. 2006). It is said the western slopes of the Western Ghats experiences heavy annual rainfall, compared to the eastern slopes. Rainfall occurs mostly in the states of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Goa, Kerala and Tamil Nadu and Dadra & Nagar Havel, decreasing from south to north (Reddy et al. 2018).

One of the most outstanding features of the Western Ghats is its massive stretches of tropical wet evergreen rainforests that covers the Peninsular India (Meyers et al. 2000). It has been claimed that the forest cover of the Western Ghats accounts for over 61,511 km2 of geographical area (Reddy et al. 2016).

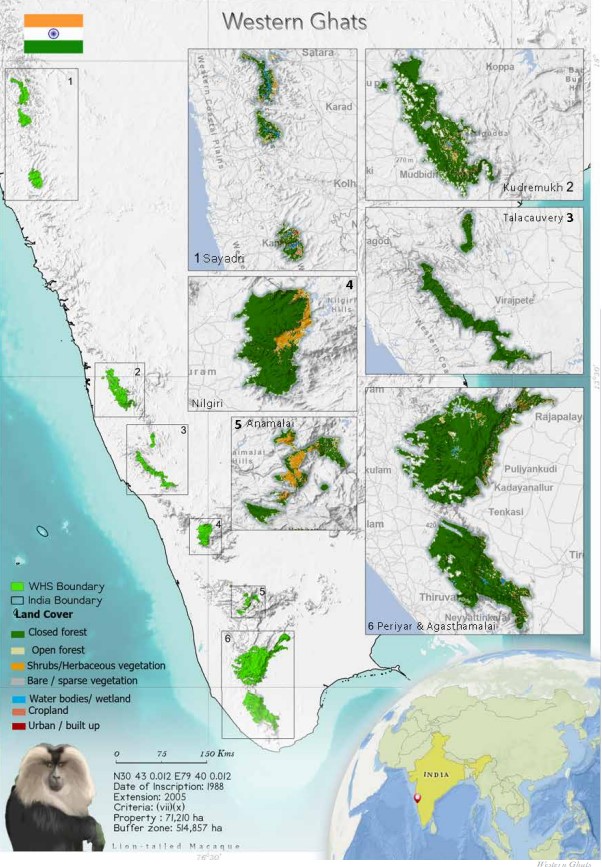

Western Ghats World heritage site is a serial property composed of 39 component parts which is assembled into 7 sub-clusters. All these 39 components are designated protected areas, ranging from Tiger Reserves, National Parks, Wildlife Sanctuaries, and Reserved Forests (UNESCO whc.unesco.org). The 7 subclusters are Sahyadri, (Kas Plateau, Koyna Wildlife Sanctuary, Chandoli National Park, Radhanagari Wildlife Sanctuary); Kudremukh (Kudremukh National Park, Someshwara Wildlife Sanctuary, Someshwara Reserved Forest, Agumbe Reserved Forest, Balahalli Reserved Forest) ; Talacauvery (Pushpagiri Wildlife Sanctuary, Brahmagiri Wildlife Sanctuary, Talacauvery Wildlife Sanctuary, Padinalknad Reserved Forest, Kerti Reserved Forest, Aralam Wildlife Sanctuary); Nilgiri (Silent Valley National Park, New Amarambalam Reserved Forest, Mukurti National Park, Kalikavu Range, Attapadi Reserved Forest); Anamalai (Eravikulam National Park, Grass Hills National Park, Karian Shola National Park, Karian Shola, Mankulam Range, Chinnar Wildlife Sanctuary, Mannavan Shola); Periyar (Periyar Tiger Reserve, Ranni Forest Division, Konni Forest Division, Achankovil Forest Division, Srivilliputtur Wildlife Sanctuary, Tirunelveli Forest Division); Agasthyamalai (Kalakad-Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve, Shendurney Wildlife Sanctuary, Neyyar Wildlife Sanctuary, Peppara Wildlife Sanctuary, Kulathupuzha Range, Palode Range).

The Western Ghats hill range runs along west coast of southern India with latitudes 7° N to 21° N, and amalgamates with Sri Lanka to form one of the world’s 34 most significant biodiversity hotspots (Kumar et al. 2004). Geographically, this famous biogeographic region extends from 080 19’08”–210 16’24” N to 720 56’24”– 780 19’40” E with a north to south distance of 1490 km, covering a total area of 136,800 km2 (CEPF 2007). This range encompasses the states of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu. Three low-altitude gaps, namely, the Sencottah gap (8° – 9° N), the Palghat gap (10° – 11° N) and the Goa gap (14° – 15° N) distinctively divide the range into southern (8° – 11° N), central (12° – 15° N) and northern (16° – 21° N) Western Ghats (Robin et al. 2010; Bocxlaer et al. 2012). These three segments are characterized by specific geoclimatic factors such as annual rainfall, mean mountain height, relief features and dominant forest types (Ganesh et al. 2013).

The climatic condition of the Western ghats is described by heavy precipitation with unique monsoon patterns (Gadgil 1996). Monsoon season is during June – September and aids in regulation of the warm tropical climate (UNESCO whc.unesco.org; Champion & Seth 1968). The mean annual temperature falls in the range of 20 – 35°C in the day and 15 – 20°C in the night (Champion & Seth 1968). The presence of mountain ranges influences the regional climate, hydrology and the distribution of vegetation types and endemic floral diversity (Gadgil & Meher-Homji 1990; Das et al. 2006). It is said the western slopes of the Western Ghats experiences heavy annual rainfall, compared to the eastern slopes. Rainfall occurs mostly in the states of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Goa, Kerala and Tamil Nadu and Dadra & Nagar Havel, decreasing from south to north (Reddy et al. 2018).

One of the most outstanding features of the Western Ghats is its massive stretches of tropical wet evergreen rainforests that covers the Peninsular India (Meyers et al. 2000). It has been claimed that the forest cover of the Western Ghats accounts for over 61,511 km2 of geographical area (Reddy et al. 2016).

Western Ghats World heritage site is a serial property composed of 39 component parts which is assembled into 7 sub-clusters. All these 39 components are designated protected areas, ranging from Tiger Reserves, National Parks, Wildlife Sanctuaries, and Reserved Forests (UNESCO whc.unesco.org). The 7 subclusters are Sahyadri, (Kas Plateau, Koyna Wildlife Sanctuary, Chandoli National Park, Radhanagari Wildlife Sanctuary); Kudremukh (Kudremukh National Park, Someshwara Wildlife Sanctuary, Someshwara Reserved Forest, Agumbe Reserved Forest, Balahalli Reserved Forest) ; Talacauvery (Pushpagiri Wildlife Sanctuary, Brahmagiri Wildlife Sanctuary, Talacauvery Wildlife Sanctuary, Padinalknad Reserved Forest, Kerti Reserved Forest, Aralam Wildlife Sanctuary); Nilgiri (Silent Valley National Park, New Amarambalam Reserved Forest, Mukurti National Park, Kalikavu Range, Attapadi Reserved Forest); Anamalai (Eravikulam National Park, Grass Hills National Park, Karian Shola National Park, Karian Shola, Mankulam Range, Chinnar Wildlife Sanctuary, Mannavan Shola); Periyar (Periyar Tiger Reserve, Ranni Forest Division, Konni Forest Division, Achankovil Forest Division, Srivilliputtur Wildlife Sanctuary, Tirunelveli Forest Division); Agasthyamalai (Kalakad-Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve, Shendurney Wildlife Sanctuary, Neyyar Wildlife Sanctuary, Peppara Wildlife Sanctuary, Kulathupuzha Range, Palode Range).

Criterion (ix)

The Western Ghats region demonstrates speciation related to the breakup of the ancient landmass of Gondwanaland in the early Jurassic period; secondly to the formation of India into an isolated landmass and the thirdly to the Indian landmass being pushed together with Eurasia. Together with favourable weather patterns and a high gradient being present in the Ghats, high speciation has resulted. The Western Ghats is an “Evolutionary Ecotone” illustrating “Out of Africa” and “Out of Asia” hypotheses on species dispersal and vicariance.

The Western Ghats region demonstrates speciation related to the breakup of the ancient landmass of Gondwanaland in the early Jurassic period; secondly to the formation of India into an isolated landmass and the thirdly to the Indian landmass being pushed together with Eurasia. Together with favourable weather patterns and a high gradient being present in the Ghats, high speciation has resulted. The Western Ghats is an “Evolutionary Ecotone” illustrating “Out of Africa” and “Out of Asia” hypotheses on species dispersal and vicariance.

Criterion (x)

The Western Ghats contain exceptional levels of plant and animal diversity and endemicity for a continental area. In particular, the level of endemicity for some of the 4-5,000 plant species recorded in the Ghats is very high: of the nearly 650 tree species found in the Western Ghats, 352 (54%) are endemic. Animal diversity is also exceptional, with amphibians (up to 179 species, 65% endemic), reptiles (157 species, 62% endemic), and fishes (219 species, 53% endemic). Invertebrate biodiversity, once better known, is likely also to be very high (with some 80% of tiger beetles endemic). A number of flagship mammals occur in the property, including parts of the single largest population of globally threatened ‘landscape’ species such as the Asian Elephant, Gaur and Tiger. Endangered species such as the lion-tailed Macaque, Nilgiri Tahr and Nilgiri Langur are unique to the area. The property is also key to the conservation of a number of threatened habitats, such as unique seasonally mass-flowering wildflower meadows, Shola forests and Myristica swamps.

Status

Although the whole range of Western Ghats are under supreme protection, some parts and their associated biodiversity are still impacted by several factors, that impose as threats to the property. Reports have claimed that large portions of the rich tropical rainforests along with a series of hill ranges in the buffer zone have been lost and several forest covers suffered fragmentation and encroachments. Manmade plantations of non-indigenous plant species such as coffee, Eucalyptus, and tea (Camellia sinensis) have substituted those lost forest covers (Kumar et al. 2004) and such trends began since 1900s, along with additional threats include hunting in many parts, which has extirpated local populations of several species and groups of terrestrial and freshwater fauna (Molur et al. 2011). For instance, the Anamalai hills used to possess large tracts of tropical rainforest that were extensively clear-felled between the 1860s and 1930s for cultivation of tea and coffee, and for teak and Eucalyptus plantations as in the Valparai plateau (Congreve 1942).

In a study that conducted vegetation analysis of the forest cover in Shendurney wildlife sanctuary, it was affirmatively reported that from 1971 to 2009, there were changes in the forest cover of the protected area, largely due to anthropogenic activities (Jose et al. 2011). A large amount of evergreen forest transformed to semi-evergreen and moist deciduous forests, indicating disturbances during that period. There were also periodic incidences of forest fire and land encroachment that added to the disturbances (Jose et al. 2011). It was also mentioned that an area of 0.123 km2 of the wildlife sanctuary is highly fragmented. There is concern of further extent of fragmentation in the near future if no conservation practices are implemented (Jose et al. 2011).

Invasion of Alien species is also on the list of factors affecting the property. For instance, in Boluvampatti range of Coimbatore forest division, 90 alien plants belonging to 74 genera were documented from the study region. Of which, 13 of the alien species were introduced by anthropogenic activities. Parthenium hysterophorus, Lantana camara, Eupatorium odoratum, Prosopis juliflora and Ageratum conyzoides were found to be highly invasive and had approached the fringes of forests as well as the core zones (Aravindhan & Rajendran 2014). In the freshwater ecosystem, Clarias gariepinus, found in the Indrayani River of the Southern Deccan Plateau ecoregion, is a potential threat to the only existing population of the rare and Endangered sisorid catfish Glyptothorax poonaensis (Dahanukar et al. 2011). There are many more such issues of introduction of alien species in several protected parts of the Western Ghats. According to the IUCN assessment of Western Ghats in 2020, the site was assessed as ‘significant concerns’.

Although the whole range of Western Ghats are under supreme protection, some parts and their associated biodiversity are still impacted by several factors, that impose as threats to the property. Reports have claimed that large portions of the rich tropical rainforests along with a series of hill ranges in the buffer zone have been lost and several forest covers suffered fragmentation and encroachments. Manmade plantations of non-indigenous plant species such as coffee, Eucalyptus, and tea (Camellia sinensis) have substituted those lost forest covers (Kumar et al. 2004) and such trends began since 1900s, along with additional threats include hunting in many parts, which has extirpated local populations of several species and groups of terrestrial and freshwater fauna (Molur et al. 2011). For instance, the Anamalai hills used to possess large tracts of tropical rainforest that were extensively clear-felled between the 1860s and 1930s for cultivation of tea and coffee, and for teak and Eucalyptus plantations as in the Valparai plateau (Congreve 1942).

In a study that conducted vegetation analysis of the forest cover in Shendurney wildlife sanctuary, it was affirmatively reported that from 1971 to 2009, there were changes in the forest cover of the protected area, largely due to anthropogenic activities (Jose et al. 2011). A large amount of evergreen forest transformed to semi-evergreen and moist deciduous forests, indicating disturbances during that period. There were also periodic incidences of forest fire and land encroachment that added to the disturbances (Jose et al. 2011). It was also mentioned that an area of 0.123 km2 of the wildlife sanctuary is highly fragmented. There is concern of further extent of fragmentation in the near future if no conservation practices are implemented (Jose et al. 2011).

Invasion of Alien species is also on the list of factors affecting the property. For instance, in Boluvampatti range of Coimbatore forest division, 90 alien plants belonging to 74 genera were documented from the study region. Of which, 13 of the alien species were introduced by anthropogenic activities. Parthenium hysterophorus, Lantana camara, Eupatorium odoratum, Prosopis juliflora and Ageratum conyzoides were found to be highly invasive and had approached the fringes of forests as well as the core zones (Aravindhan & Rajendran 2014). In the freshwater ecosystem, Clarias gariepinus, found in the Indrayani River of the Southern Deccan Plateau ecoregion, is a potential threat to the only existing population of the rare and Endangered sisorid catfish Glyptothorax poonaensis (Dahanukar et al. 2011). There are many more such issues of introduction of alien species in several protected parts of the Western Ghats. According to the IUCN assessment of Western Ghats in 2020, the site was assessed as ‘significant concerns’.