Ujung Kulon National Park (608)

Ujung Kulon National Park has a very beautiful landscape, being surrounded by the sea and having been shaped by successive vegetation and volcanic activity. The place is of great interest because of the several endangered plants and animals and because it is the last and most important natural habitat of the single-horned Javan rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus). The park houses the last viable natural population of this species, which has approximately 60 individuals. Ujung Kulon is located at the south-western tip of Java, on the Sunda shelf. The property also has Ujung Kulon Peninsular and several offshore islands, besides the nature reserve of Krakatoa Volcano. The site is of great significance for the study of volcanoes. It also contains the largest remaining area under lowland rainforests in the Java plain. The park serves as a great example of ongoing evolution of geological processes after the Krakatau eruption in 1883. This volcano has a very significant role in the study of modern volcanic eruptions. The place houses 57 rare species of plant, 35 species of mammal, 72 species of reptile and amphibian and 240 species of bird. The current level of threats low to this property. Hunting of the Javan Rhinoceros was the major issue but due to some strict management plans, no hunting of rhinos has been found in the past 22 years. The rhinoceros population faces a challenge in the overabundance of Arenga obtusifolia, which is a native palm species and is causing a reduction in the natural habitat of the rhinoceros.

Ujung Kulon National Park has a very beautiful landscape, being surrounded by the sea and having been shaped by successive vegetation and volcanic activity. The place is of great interest because of the several endangered plants and animals and because it is the last and most important natural habitat of the single-horned Javan rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus). The park houses the last viable natural population of this species, which has approximately 60 individuals. Ujung Kulon is located at the south-western tip of Java, on the Sunda shelf. The property also has Ujung Kulon Peninsular and several offshore islands, besides the nature reserve of Krakatoa Volcano. The site is of great significance for the study of volcanoes. It also contains the largest remaining area under lowland rainforests in the Java plain. The park serves as a great example of ongoing evolution of geological processes after the Krakatau eruption in 1883. This volcano has a very significant role in the study of modern volcanic eruptions. The place houses 57 rare species of plant, 35 species of mammal, 72 species of reptile and amphibian and 240 species of bird. The current level of threats low to this property. Hunting of the Javan Rhinoceros was the major issue but due to some strict management plans, no hunting of rhinos has been found in the past 22 years. The rhinoceros population faces a challenge in the overabundance of Arenga obtusifolia, which is a native palm species and is causing a reduction in the natural habitat of the rhinoceros.

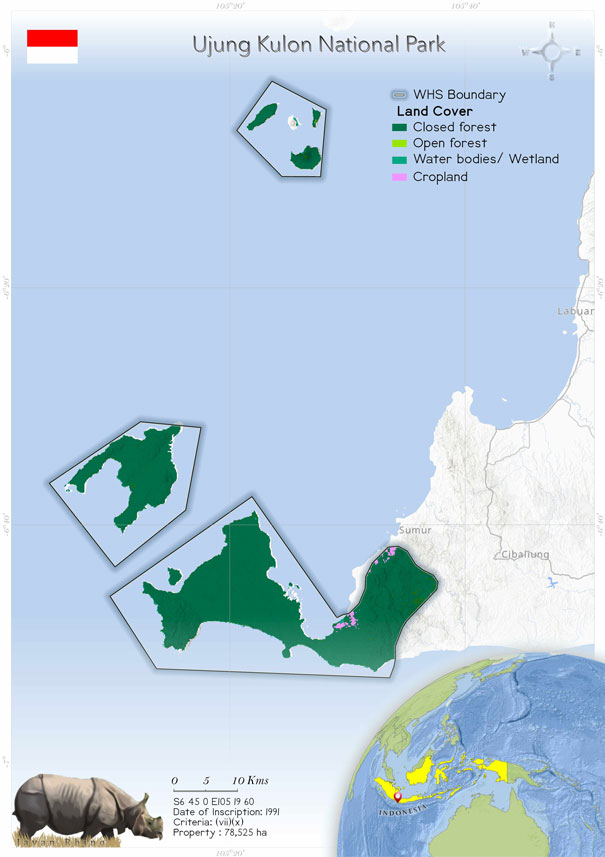

Ujung Kulon National Park is situated between 102° 2' 32" and 105° 37' 37" E and between 6° 30' 43" and 6° 52' 17" S (Mujiono 2008), at the extreme south-western tip of Java, on the Sunda shelf (Gallegos et al. 2005), in the Sumur and Cimanggu sub-districts, Pandeglang District and Banten Province (Mujiono 2008). The park is bordered by Gunung Payung (480 m) in the west and by Gunung Honje in the east (Santiapillai et al. 1990). Ujung Kulon National Park includes the Ujung Kulon peninsula, the surrounding reefs, the marine area, including some offshore islands, namely, Handeuleum, Peucang and Panaitan, (Peggie 2012) and the natural reserve of Krakatau (Gallegos et al. 2005).

The park was designated as a nature reserve in 1921 (the Krakatoa area). Two more nature reserve areas were formed in 1937. Ujung Kulon Nature was created in 1958. In 1992, all these natural reserves (Ujung Kulon Peninsula, Panaitan Island, the Krakatoa Islands’ nature reserves) got combined into a national park (Claudino 2019). This property was declared a World Heritage Site in 1991. The park has the largest area of lowland rainforests in the Jana plain and habitats like a swamp, mangroves, a beach forest and coral reefs. Almost 40% of the site is marine (Gallegos et al. 2005). The mean annual rainfall in the park is 3250 mm. The heaviest rainfall is recorded between October and September. The driest period is between May and September.

The property is a good example of the evolution of geographical processes, having different environments after the Krakatoa eruption in 1883. The park has a mix of the natural vegetation of the lowlands, tropical rainforests, grasslands, beach forests, mangrove forests and coral reefs. The vegetation is mainly semi-evergreen rainforest, mostly secondary growth after the volcanic eruption. The vegetation primarily consists of palms (Arenga pinnata and A. obtusifolia), wild sugarcane and rattan (Calamus melanoloma and other species) (World Heritage datasheet 2011).

The site has a rich avifauna with more than 270 species. The marine fauna is also found in abundance in the archipelago, with deep water and reef species (Claudino 2019).

Ujung Kulon National Park is mainly known for the presence of the Javan rhino (Rhinoceros sondaicus sondaicus), which is restricted entirely within the park boundaries. This species is also listed in the Critically Endangered on IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species.

Ujung Kulon National Park is situated between 102° 2' 32" and 105° 37' 37" E and between 6° 30' 43" and 6° 52' 17" S (Mujiono 2008), at the extreme south-western tip of Java, on the Sunda shelf (Gallegos et al. 2005), in the Sumur and Cimanggu sub-districts, Pandeglang District and Banten Province (Mujiono 2008). The park is bordered by Gunung Payung (480 m) in the west and by Gunung Honje in the east (Santiapillai et al. 1990). Ujung Kulon National Park includes the Ujung Kulon peninsula, the surrounding reefs, the marine area, including some offshore islands, namely, Handeuleum, Peucang and Panaitan, (Peggie 2012) and the natural reserve of Krakatau (Gallegos et al. 2005).

The park was designated as a nature reserve in 1921 (the Krakatoa area). Two more nature reserve areas were formed in 1937. Ujung Kulon Nature was created in 1958. In 1992, all these natural reserves (Ujung Kulon Peninsula, Panaitan Island, the Krakatoa Islands’ nature reserves) got combined into a national park (Claudino 2019). This property was declared a World Heritage Site in 1991. The park has the largest area of lowland rainforests in the Jana plain and habitats like a swamp, mangroves, a beach forest and coral reefs. Almost 40% of the site is marine (Gallegos et al. 2005). The mean annual rainfall in the park is 3250 mm. The heaviest rainfall is recorded between October and September. The driest period is between May and September.

The property is a good example of the evolution of geographical processes, having different environments after the Krakatoa eruption in 1883. The park has a mix of the natural vegetation of the lowlands, tropical rainforests, grasslands, beach forests, mangrove forests and coral reefs. The vegetation is mainly semi-evergreen rainforest, mostly secondary growth after the volcanic eruption. The vegetation primarily consists of palms (Arenga pinnata and A. obtusifolia), wild sugarcane and rattan (Calamus melanoloma and other species) (World Heritage datasheet 2011).

The site has a rich avifauna with more than 270 species. The marine fauna is also found in abundance in the archipelago, with deep water and reef species (Claudino 2019).

Ujung Kulon National Park is mainly known for the presence of the Javan rhino (Rhinoceros sondaicus sondaicus), which is restricted entirely within the park boundaries. This species is also listed in the Critically Endangered on IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species.

Criterion (vii)

Krakatau is one of natural world’s best-known examples of recent island volcanism and the property with its forests, coastline and islands is a natural landscape of high scenic attraction. The physical feature of Krakatau Island combined with the surrounding sea, natural vegetation, succession of vegetation and volcanic activities combine to form a landscape of exceptional beauty. In addition, the combination of natural vegetation of the lowlands, tropical rainforests, and grass lands, beach forests, mangrove forests and coral reefs within the property, are of exceptional magnificence. The property includes the Ujung Kulon peninsula and several offshore islands that demonstrate on-going evolutionary processes, especially following the dramatic Krakatau eruption in 1883

Krakatau is one of natural world’s best-known examples of recent island volcanism and the property with its forests, coastline and islands is a natural landscape of high scenic attraction. The physical feature of Krakatau Island combined with the surrounding sea, natural vegetation, succession of vegetation and volcanic activities combine to form a landscape of exceptional beauty. In addition, the combination of natural vegetation of the lowlands, tropical rainforests, and grass lands, beach forests, mangrove forests and coral reefs within the property, are of exceptional magnificence. The property includes the Ujung Kulon peninsula and several offshore islands that demonstrate on-going evolutionary processes, especially following the dramatic Krakatau eruption in 1883

Criterion (x)

Containing the most extensive remaining stand of lowland rainforest on Java, a habitat that has virtually disappeared elsewhere on the island and is under severe pressure elsewhere in Indonesia and Southeast Asia, the peninsula of Ujung Kulon provides invaluable habitat critical for the survival of a number of threatened plant and animal species, most notably the endangered Javan Rhino (Rhinoceros sondaicus). The Javan rhino is not known to occur in the wild anywhere else on earth and Ujung Kulon is believed to sustain the last viable natural population, estimated at approximately 60 individuals. Efforts to protect the Javan rhino’s remaining habitat and individuals have become a symbol for protection of rainforest of worldwide significance, adding to the international importance of the management and preservation of the Ujung Kulon ecosystem. The property also provides a valuable refuge for 29 other species of mammals; nine of which are on the IUCN red list with three species considered endangered and including leopard (Panthera pardus), the endemic Javan gibbon (Mylobates moloch) and Javan leaf monkey (Presbytis comata). Avifauna recorded within the property includes 270 species while two species of crocodile, the endangered false gharial (Tomistoma schlegelii) and the vulnerable estuarine crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) are included in the reptile and amphibian species recorded for the property. In addition to the rich fauna 57 species of rare plants have also been recorded.

Status

The park is headed by the Directorate General of Forest Protection and Nature Conservation under the Ministry of Forestry. The stakeholders from the local, national and international community have reconciled, which has improved the conservation of the values and integrity of the park (UNESCO whc. unesco.org). According to IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2020, Ujung Kulon National Park is in the category “good with some concerns.” According to the recent assessment done by IUCN, the level of infringement and illegal activities is relatively low. However, there are still some threats like poaching, buffalo grazing and illegal shrimp fry collection. Although no poaching of rhinoceroses has been recorded during the past 22 years, many bird species in Ujung Kulon National Park have a high market value. Thus, poaching of avifauna is very common in the park. Other mammals, such as the mouse deer and banteng, and green turtles are also being hunted. The Javan rino faces a massive challenge from Arenga obtusifolia, a native palm species. The overabundance of this palm has reduced the habitat and the availability of food plants (IUCN Outlook 2020). The large population of Javan banteng (Bos javanicus) is also having a negative impact on the rhino population as the banteng’s feeding ecology overlaps with that of the rhino (strategy and action plan for the conservation of rhinos in Indonesia 2007).

Krakatau is part of the property and part of its outstanding Universal Value (OUV). It is still prone to volcanic activity, earthquakes and tsunamis, which can cause harm to the property. The volcanic eruption of 1883 caused a tsunami of 15 m, which damaged many forests along the beaches (IUCN Outlook 2020). The long-term survival of the Javan rhinoceros and other endangered species in the park has been incorporated into management plans. The Strategy and Action Plan for Rhino Conservation in Indonesia (2007-2017) were innovative, developed through broad, open, and transparent participatory processes, and have contributed to the future survival of the critically endangered Javan rhino species. Under this plan, a new sanctuary was developed within the park, these additional sites served as an habitat for the rhino species. This plan also highlighted threats such as inbreeding, global warming and human pressure for Javan Rhino(UNESCO whc.unesco.org). The park is getting support at the national and international levels for conservation. The area has been funded by international bodies like UNEP, UNDP, World Bank and UNESCO (Periodic report summary, 2003). WWF also contributed to saving the last few Javan rhinos of the park. WWF runs several projects in UKNP through its Asian, Rhino, and Elephant Action Strategy (AREAS) (strategy and action plan for the conservation of rhinos in Indonesia, 2007). At the national level, the property gets funded by the central government’s budget. The local communities depend directly on the park for their living, causing stress to the park’s diversity. Several tours are being organized by trained staff members from the local community to promote eco-tourism that minimizes the stress.

The park is headed by the Directorate General of Forest Protection and Nature Conservation under the Ministry of Forestry. The stakeholders from the local, national and international community have reconciled, which has improved the conservation of the values and integrity of the park (UNESCO whc. unesco.org). According to IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2020, Ujung Kulon National Park is in the category “good with some concerns.” According to the recent assessment done by IUCN, the level of infringement and illegal activities is relatively low. However, there are still some threats like poaching, buffalo grazing and illegal shrimp fry collection. Although no poaching of rhinoceroses has been recorded during the past 22 years, many bird species in Ujung Kulon National Park have a high market value. Thus, poaching of avifauna is very common in the park. Other mammals, such as the mouse deer and banteng, and green turtles are also being hunted. The Javan rino faces a massive challenge from Arenga obtusifolia, a native palm species. The overabundance of this palm has reduced the habitat and the availability of food plants (IUCN Outlook 2020). The large population of Javan banteng (Bos javanicus) is also having a negative impact on the rhino population as the banteng’s feeding ecology overlaps with that of the rhino (strategy and action plan for the conservation of rhinos in Indonesia 2007).

Krakatau is part of the property and part of its outstanding Universal Value (OUV). It is still prone to volcanic activity, earthquakes and tsunamis, which can cause harm to the property. The volcanic eruption of 1883 caused a tsunami of 15 m, which damaged many forests along the beaches (IUCN Outlook 2020). The long-term survival of the Javan rhinoceros and other endangered species in the park has been incorporated into management plans. The Strategy and Action Plan for Rhino Conservation in Indonesia (2007-2017) were innovative, developed through broad, open, and transparent participatory processes, and have contributed to the future survival of the critically endangered Javan rhino species. Under this plan, a new sanctuary was developed within the park, these additional sites served as an habitat for the rhino species. This plan also highlighted threats such as inbreeding, global warming and human pressure for Javan Rhino(UNESCO whc.unesco.org). The park is getting support at the national and international levels for conservation. The area has been funded by international bodies like UNEP, UNDP, World Bank and UNESCO (Periodic report summary, 2003). WWF also contributed to saving the last few Javan rhinos of the park. WWF runs several projects in UKNP through its Asian, Rhino, and Elephant Action Strategy (AREAS) (strategy and action plan for the conservation of rhinos in Indonesia, 2007). At the national level, the property gets funded by the central government’s budget. The local communities depend directly on the park for their living, causing stress to the park’s diversity. Several tours are being organized by trained staff members from the local community to promote eco-tourism that minimizes the stress.