Tasmanian Wilderness (181)

The Tasmanian Wilderness is mixed World

Heritage Site located in the state of Tasmania state

in Australia. The property is spread over a million

hectares, and it covers 20% of the land of Tasmania.

The site is inscribed as a World Heritage Site because

of the universal values of the rocks and landforms and

the unique properties of the soil. This site is situated

at a remote location. There are no roads, human

settlements, agriculture and other development inside

the area. Within the property many aboriginal sites

were discovered in 1981. These sites are nearly 20,000

years old. A number of these sites are examples of

ongoing and undisturbed karst processes. The area

is home to 30 mammal species, of which three are

endemic to Tasmania, and 120 species of bird, of which

10 are endemic to the park. and seven frog species

are reported. The aquatic fauna includes 16 freshwater

species, and 68 marine fish species are found in the

park. The site is managed by the joint Commonwealth &

State arrangements. under which there are a standing

committee of officials and a 15-member consultative

committee of scientific, aboriginal, industry and

recreational interests. It is protected by the National

Parks & Wildlife Act (1970). Threats to the property

include forest fires, pathogens of fresh water, invasive

alien species and impacts of climate change.

The Tasmanian Wilderness is mixed World

Heritage Site located in the state of Tasmania state

in Australia. The property is spread over a million

hectares, and it covers 20% of the land of Tasmania.

The site is inscribed as a World Heritage Site because

of the universal values of the rocks and landforms and

the unique properties of the soil. This site is situated

at a remote location. There are no roads, human

settlements, agriculture and other development inside

the area. Within the property many aboriginal sites

were discovered in 1981. These sites are nearly 20,000

years old. A number of these sites are examples of

ongoing and undisturbed karst processes. The area

is home to 30 mammal species, of which three are

endemic to Tasmania, and 120 species of bird, of which

10 are endemic to the park. and seven frog species

are reported. The aquatic fauna includes 16 freshwater

species, and 68 marine fish species are found in the

park. The site is managed by the joint Commonwealth &

State arrangements. under which there are a standing

committee of officials and a 15-member consultative

committee of scientific, aboriginal, industry and

recreational interests. It is protected by the National

Parks & Wildlife Act (1970). Threats to the property

include forest fires, pathogens of fresh water, invasive

alien species and impacts of climate change.

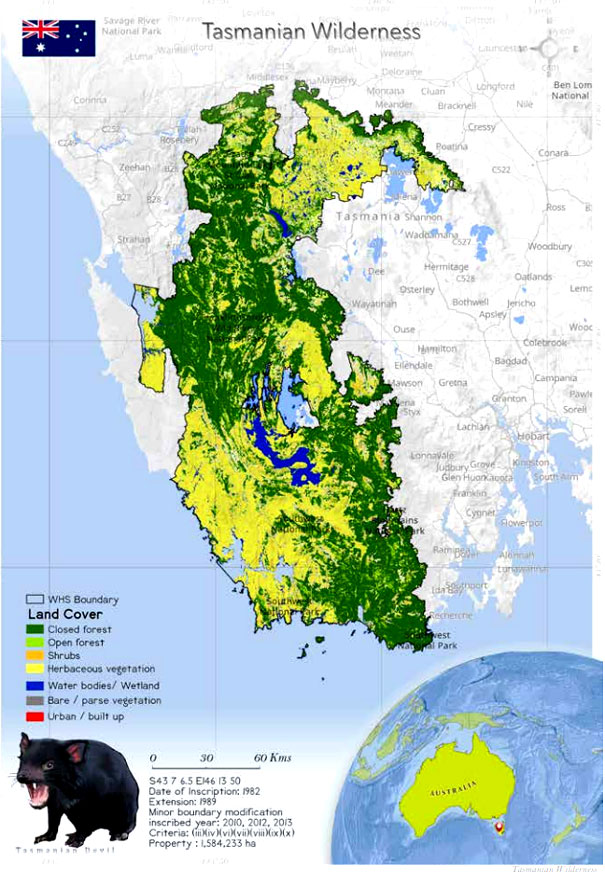

Tasmania is part of an archipelago consisting

of 334 islands situated between 30 km and 1700 km

southeast of mainland Australia (Sharples 2003). The

Tasmania Wilderness stretches over an area of 1,584,233

ha extent (UNESCO), which includes 20% of the land area

Tasmania (Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003). The place is

a World Heritage Site because of the universal values of

its rocks and landforms and its unique soil properties.

A large portion of the New River basin in southwest

Tasmania falls within the World Heritage Site. The extent

of the basin is 309 km2

. There is no human disturbance

in this area. It has no roads, no human settlements, no

agriculture and no other development.

The area is covered by with forests and other forms

of vegetation cover, with native species (Houshold

& Sharples 2008). A great range of temperatures is

experienced in the area, and it has diverse landforms,

soils and bedrocks. The rocks of the site are from the

Holocene-to-Precambrian period (Sharples 2003). There

are records of the Pleistocene aboriginal occupation,

35,000 years back. Holocene middens and the convict

history of the 19th century add to the universal values of

the property (Russell & Jambrecina 2002).

The property has many aboriginal sites, many of which

are 20,000 years old. These were discovered only after

1981. Fraser Cave is the most important of these sites

as it is the last human outpost in the Antarctic ice-cap.

There are many examples at the site of ongoing and

undisturbed karst processes. Paleokarst development,

which occurred 400 million years ago, hydrothermal

karstification and evidence of past glacio-karstic

interactions are also seen in the park (UNEP-WCMC

2012).

Three national parks of the property—Southwest

(442,240 ha), Franklin-Gordon Wild Rivers (195,200 ha)

and Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair (131,915 ha) national

parks—together make up the world's last pristine

temperate wilderness (World Heritage Nomination

1982). A spectacular view of glaciated landscape can

be had within the boundaries of the property, at Cradle

Mountain. This is described in the tourist literature as an

iconic Tasmanian mountain.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the mountain was

declared a national park. It was the first to be declared a

national park in western Tasmania (Houshold & Sharples

2008). The property was declared a World Heritage Site

in 1982, and in 1989 it was extended (World Heritage

Nomination 2010) as the Western Tasmania Wilderness

National Parks World Heritage Area. This international

status has caused a reduction in the developmental

activities affecting the property. In 2010, the property

got extended again to include 21 small areas from

national parks or state reserves around the eastern and

southern boundaries.

The place has rocks which are from every geological

period, and there are unique landscapes. The deepest

and longest caves of Australia are present here. There

are more than 40 caves, including Kutikina Cave and

other rock art sites. These caves hold “exceptional

cultural, emotional and spiritual value” for the aboriginal

community, and they are excellent examples of human

interaction with nature and the climate that prevailed

during the ice age (Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003).

The area is the best place to study the adaptations of

prehistoric populations to extreme climatic conditions

(World Heritage Nomination 1982).

The place has unique landforms, marvellous examples

of cool temperate rainforests, some important aboriginal

sites and many endangered species of plant and animal.

Southwest National Park is a biosphere reserve (World

Heritage Nomination 1982). The land is home to various

endemic species including the orange-bellied parrot

and burrowing crayfish. There are some animals from

ancient relict groups, including the world's largest

marsupial carnivores, the Tasmanian devil, the spotted-

tailed quoll and the eastern quoll. There have been new

species discoveries in the marine environment. These

include skate sea pen species. The oldest documented

(43,000 years old) vascular plant clone was discovered

in the area, as well as many terrestrial species such as

the moss froglet, the mountain skink, the fern ally and

a lichen (Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003). According to

Mallick and Driessen (2005), around 1397 terrestrial/

freshwater species belonging to 293 families, from nine

phyla, are present in the World Heritage Site. Sixtythree species and six phyla have been observed in

marine and freshwater habitats. There are 16 threatened

invertebrate species (Mallick & Driessen 2005). The

area is home to 30 mammal species, of which three are

endemic to Tasmania, 120 species of bird, of which 10 are

endemic, and seven frog species. The aquatic fauna of

the park includes 16 freshwater species and 68 marine

fishes (Driessen & Mallick 2003).

Tasmania is part of an archipelago consisting

of 334 islands situated between 30 km and 1700 km

southeast of mainland Australia (Sharples 2003). The

Tasmania Wilderness stretches over an area of 1,584,233

ha extent (UNESCO), which includes 20% of the land area

Tasmania (Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003). The place is

a World Heritage Site because of the universal values of

its rocks and landforms and its unique soil properties.

A large portion of the New River basin in southwest

Tasmania falls within the World Heritage Site. The extent

of the basin is 309 km2

. There is no human disturbance

in this area. It has no roads, no human settlements, no

agriculture and no other development.

The area is covered by with forests and other forms

of vegetation cover, with native species (Houshold

& Sharples 2008). A great range of temperatures is

experienced in the area, and it has diverse landforms,

soils and bedrocks. The rocks of the site are from the

Holocene-to-Precambrian period (Sharples 2003). There

are records of the Pleistocene aboriginal occupation,

35,000 years back. Holocene middens and the convict

history of the 19th century add to the universal values of

the property (Russell & Jambrecina 2002).

The property has many aboriginal sites, many of which

are 20,000 years old. These were discovered only after

1981. Fraser Cave is the most important of these sites

as it is the last human outpost in the Antarctic ice-cap.

There are many examples at the site of ongoing and

undisturbed karst processes. Paleokarst development,

which occurred 400 million years ago, hydrothermal

karstification and evidence of past glacio-karstic

interactions are also seen in the park (UNEP-WCMC

2012).

Three national parks of the property—Southwest

(442,240 ha), Franklin-Gordon Wild Rivers (195,200 ha)

and Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair (131,915 ha) national

parks—together make up the world's last pristine

temperate wilderness (World Heritage Nomination

1982). A spectacular view of glaciated landscape can

be had within the boundaries of the property, at Cradle

Mountain. This is described in the tourist literature as an

iconic Tasmanian mountain.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the mountain was

declared a national park. It was the first to be declared a

national park in western Tasmania (Houshold & Sharples

2008). The property was declared a World Heritage Site

in 1982, and in 1989 it was extended (World Heritage

Nomination 2010) as the Western Tasmania Wilderness

National Parks World Heritage Area. This international

status has caused a reduction in the developmental

activities affecting the property. In 2010, the property

got extended again to include 21 small areas from

national parks or state reserves around the eastern and

southern boundaries.

The place has rocks which are from every geological

period, and there are unique landscapes. The deepest

and longest caves of Australia are present here. There

are more than 40 caves, including Kutikina Cave and

other rock art sites. These caves hold “exceptional

cultural, emotional and spiritual value” for the aboriginal

community, and they are excellent examples of human

interaction with nature and the climate that prevailed

during the ice age (Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003).

The area is the best place to study the adaptations of

prehistoric populations to extreme climatic conditions

(World Heritage Nomination 1982).

The place has unique landforms, marvellous examples

of cool temperate rainforests, some important aboriginal

sites and many endangered species of plant and animal.

Southwest National Park is a biosphere reserve (World

Heritage Nomination 1982). The land is home to various

endemic species including the orange-bellied parrot

and burrowing crayfish. There are some animals from

ancient relict groups, including the world's largest

marsupial carnivores, the Tasmanian devil, the spotted-

tailed quoll and the eastern quoll. There have been new

species discoveries in the marine environment. These

include skate sea pen species. The oldest documented

(43,000 years old) vascular plant clone was discovered

in the area, as well as many terrestrial species such as

the moss froglet, the mountain skink, the fern ally and

a lichen (Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003). According to

Mallick and Driessen (2005), around 1397 terrestrial/

freshwater species belonging to 293 families, from nine

phyla, are present in the World Heritage Site. Sixtythree species and six phyla have been observed in

marine and freshwater habitats. There are 16 threatened

invertebrate species (Mallick & Driessen 2005). The

area is home to 30 mammal species, of which three are

endemic to Tasmania, 120 species of bird, of which 10 are

endemic, and seven frog species. The aquatic fauna of

the park includes 16 freshwater species and 68 marine

fishes (Driessen & Mallick 2003).

Criterion (iii)

The Tasmanian Wilderness bears an exceptional

testimony to the southernmost occupation by people

during the Pleistocene period. Cave sites contain

extremely rich, exceptionally well-preserved occupation

deposits of bone and stone artefacts. Well preserved,

diverse rock marking sites and rock shelter sites

provide evidence of Aboriginal occupation, dating back

approximately 40,000 years.

The Tasmanian Wilderness bears an exceptional

testimony to the southernmost occupation by people

during the Pleistocene period. Cave sites contain

extremely rich, exceptionally well-preserved occupation

deposits of bone and stone artefacts. Well preserved,

diverse rock marking sites and rock shelter sites

provide evidence of Aboriginal occupation, dating back

approximately 40,000 years.

Criterion (iv)

The Tasmanian Wilderness is a diverse cultural landscape where Aboriginal people have managed and modified the landscape for approximately 40,000 years. Significant stages in human history, from the Pleistocene period to the arrival of Europeans, are illustrated through extensive and diverse Holocene shell middens, rock shelters and artefact scatters, as well as Aboriginal cultural heritage sites. Targeted Aboriginal burning regimes are evidenced in the modified vegetation types within this landscape.

Criterion (vi)

Rock marking sites provide a tangible reflection of the beliefs and ideas of the southernmost people in the world during the Pleistocene, and of their descendants in later periods. Red ochre hand stencils, ochre smears, and other amorphous marks have been found in caves throughout the property. Amongst these sites is Wargata Mina which is the southernmost known Pleistocene marking site in Tasmania, and the first site in the world where mammal blood was identified as being mixed with ochre, possibly as a fixative. The vast majority of rock markings in the caves are individual motifs, spatially separated from one another. This suggests a spiritual or artistic intent, highlighting a considered, organised and arranged approach to the creation of markings, which is supported by the absence of cultural materials or occupation deposits. The rock markings and cave hand stencils together represent a close connection to ideas and beliefs and living traditions of Tasmanian Aboriginal people and their ancestors.

Criterion (vii)

Geological and glacial events, climatic variation at the geological and landscape scales, and Aboriginal occupation and use have combined to produce extensive and varied wilderness landscapes of exceptional aesthetic importance abound. Important landscape features exemplifying the variety and beauty of the property include the rugged, tarn-embedded quartzite ranges, such as the Eastern Arthurs. The dramatic rampart of the Great Western Tiers, marks the northern and eastern bounds of the undulating alpine Central Plateau, where sand dunes with ancient pencil pines abut shallow lakes. Dark-watered estuaries, such as New River Lagoon, nestle below precipitous peaks. The wild and windy coast with its emerald marsupial lawns, and the bizarrely beautiful submarine ecosystems of Port Davey and Bathurst Harbour add to the aesthetic appeal of the property. The golds and greens of wind-moulded alpine and subalpine flora, extensive blankets of buttongrass moorlands and patches of dark green mossy rainforests cloaking southern slopes, contribute to its scenic diversity. Cave systems are ornamented by glow worms, wild rivers cut dramatically through quartzite ranges to calmer water below, and forests dominated by Mountain Ash, at 70-100 metres, dwarf the rainforest understorey below.

Criterion (viii)

Extensive outcrops of Jurassic dolerite attest to the breakup of Gondwana more than 40 million years ago. Large areas of terrace systems, stabilized by a peat coating, provide evidence of tectonic and sea level change. Vast areas of wilderness and wild coasts, free of exotic plants, allow fluvial, aeolian and wave-driven processes to continue. Periglacial processes, globally unusual because of the absence of permafrost, actively create stone stripes, polygons and steps. Globally distinct wind-controlled striped mires are the product of ongoing bio-geomorphological processes, as are the peat pond systems. The accumulation of organic matter continues at a landscape scale in nutrient-poor quartzite country, where globally distinct, reddish fibric moor peats occur at depth under rainforest. The property contains globally outstanding exemplars of ongoing temperate maritime karst processes, unusually within dolomite. Palaeokarst, much resulting from the unusual interaction of glacial and karst processes in a maritime climate, provides one of the best available global records of southern temperate glacial processes, with deposits from three eras: the late Cenozoic, late Paleozoic and late Proterozoic.

Criterion (ix)

The property’s great size and wilderness character enable significant natural, biological and geomorphological processes to continue in terrestrial, coastal, riverine and mountain ecosystems. The property is exceptional in its representation of ongoing terrestrial ecological processes involving fire and wind. Mosaic landscapes of fire-susceptible and fire-dependent plant communities have formed. These include large, remote, undisturbed areas of Mountain Ash, one of the tallest flowering plants in the world. At alpine altitudes, where wind redistributes sporadic snowfalls, cushion plants, exposed to wind and ice abrasion, thrive. Distinct plant communities, including the only Australian winter deciduous tree, the Deciduous Beech (also known as Tanglefoot), form on fire and weather protected northeastern slopes. Wind-controlled cyclic succession in lineated Sphagnum mires appears to be globally unique. Unusual assemblages of deep marine species are found within the large estuaries, where communities are moderated by dark tannic freshwater, overlaying salt.

Criterion (x)

Extensive areas of high wilderness quality ensure habitats of sufficient size to allow the survival of endemic and rare or threatened species such as the Tasmanian wedge-tailed eagle, and many ancient taxa with links to Gondwana. The orange-bellied parrot and an assemblage of marsupial carnivores are found nowhere else. Some of the longest-lived trees in the world are present, with Huon pines reaching ages in excess of 2000 years. Secure habitats, including hundreds of island refuges, contain very few pathogens, weeds, or pests. Spectacular cave systems are inhabited by endemic invertebrate species, resulting from relict populations separated during periods of glaciation. The world’s most southerly and isolated temperate seagrass beds and giant kelp forests occur in Port Davey and Bathurst Harbour and remote islands support significant breeding populations of seabirds.

Status

The first management plan of the property

(1992–1999) was reviewed after 5 years, and a new plan

(a 10-year plan) was framed by the Tasmania Parks and

Wildlife Service in 1999 (Russell & Jambrecina 2002).

Ninety percent of the park is protected by the National

Parks and Wildlife Act (1970). It has been declared by the

law that “no statutory powers can be exercised within

a state reserve, unless authorized by a management

plan.”

The property is managed by joint Commonwealth–

State arrangements, under which there is a standing

committee of officials and a 15-member consultative

committee of scientific, aboriginal, industry and

recreational interests. Since 1995, the Aboriginal Land

Council has been supervising Kutikina Cave (15 ha)

and other “parcels of land”, and the Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act (1984)

provides the highest protection to the aboriginal sites

from violation (Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003). Forest

fires were a significant threat to the property, but the

implementation of some models helped reduce forest

loss by producing some fire-free vegetation. The forest

cover increased by 4.1% during the period 1948–1988 and

by 0.8% during the period 1988–2010 (Wood & Bowman

2012).

The pets and pathogens of the freshwater are

also turning out to be a serious hazard. Pets and

pathogens such as Phytophthora cinnamomi (root rot),

Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (chytrid frog disease),

Mucor amphibiorum (platypus mucor disease) and the

freshwater algal pest Didymosphenia geminata (didymo)

are causing harm to the native freshwater species (Allan

& Gartenstein 2010). The current threats to the property

are quite serious. The “landscape- scale” bushfire of

2000 caused a lot of damage to the property, and 12%

of the area got affected, specifically in the high-altitude

region of the heritage site The increasing tourism

can cause harm to the property. Climate change is

having direct and indirect impacts on the property—

the increased frequency and intensity of fires is also

an effect of climate change, and these fires can cause

damage if measures are not taken (IUCN World Heritage

Outlook 2020). There is a programme for eradication

of feral dogs from the property. Other programmes

have been implemented for reducing the numbers of

starlings and rabbits (Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003).

The remoteness, location, limited resources and harsh

environment have provided the area a high degree

of natural protection. The area of the site has been

increased through a series of extensions, as “minor

boundary modifications”, in 1989, 2010, 2012 and 2013,

which has provided the property an extra layer of

protection. According to the State of Conservation

Report of 2021, a tourism master plan is being

developed that will provide guide policies and increase

the range of tourism-related experiences available to

visitors. According to the State of Conservation Report

of 2018, the management of the park is effective

and is perpetuating the values of the park. Threats

faced in some areas such as the sea level rise and

effects of climate change cannot be controlled by the

management (IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2020)

The monitoring and evaluation of the property

for adaptive management is mostly effective, and it

commits to providing regular reports of TWWHA (IUCN

World Heritage Outlook 2020).

In December 2016, a new management plan was

implemented under Tasmania’s Nature Conservation

Act 2002. The new management plan includes banning

of logging and mining activities inside the property, and

it facilitates joint management arrangements with the

Tasmanian aboriginal people to support and improve

their cultural heritage values (IUCN World Heritage

Outlook 2020).

The Aboriginal Heritage Council provides advice and

guides the development of the plan to carry out an

assessment of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage

Site. The State party states about appointing the

specific reserve zone for Permanent Timber Production

Zone Land (PTPZL) and Future Potential Production

Forest Land (FPPFL) upon community consultation.

The Committee requests the state party to speed the

process of designation (State of Conservation Report

of 2021). Funds to the tune of AUD 3.2 million (USD

2.5 million) have been released for the protection of

the endangered orange-bellied parrots (Neophema

chrysogaster) (State of Conservation Report of 2018).

The first management plan of the property

(1992–1999) was reviewed after 5 years, and a new plan

(a 10-year plan) was framed by the Tasmania Parks and

Wildlife Service in 1999 (Russell & Jambrecina 2002).

Ninety percent of the park is protected by the National

Parks and Wildlife Act (1970). It has been declared by the

law that “no statutory powers can be exercised within

a state reserve, unless authorized by a management

plan.”

The property is managed by joint Commonwealth–

State arrangements, under which there is a standing

committee of officials and a 15-member consultative

committee of scientific, aboriginal, industry and

recreational interests. Since 1995, the Aboriginal Land

Council has been supervising Kutikina Cave (15 ha)

and other “parcels of land”, and the Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act (1984)

provides the highest protection to the aboriginal sites

from violation (Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003). Forest

fires were a significant threat to the property, but the

implementation of some models helped reduce forest

loss by producing some fire-free vegetation. The forest

cover increased by 4.1% during the period 1948–1988 and

by 0.8% during the period 1988–2010 (Wood & Bowman

2012).

The pets and pathogens of the freshwater are

also turning out to be a serious hazard. Pets and

pathogens such as Phytophthora cinnamomi (root rot),

Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (chytrid frog disease),

Mucor amphibiorum (platypus mucor disease) and the

freshwater algal pest Didymosphenia geminata (didymo)

are causing harm to the native freshwater species (Allan

& Gartenstein 2010). The current threats to the property

are quite serious. The “landscape- scale” bushfire of

2000 caused a lot of damage to the property, and 12%

of the area got affected, specifically in the high-altitude

region of the heritage site The increasing tourism

can cause harm to the property. Climate change is

having direct and indirect impacts on the property—

the increased frequency and intensity of fires is also

an effect of climate change, and these fires can cause

damage if measures are not taken (IUCN World Heritage

Outlook 2020). There is a programme for eradication

of feral dogs from the property. Other programmes

have been implemented for reducing the numbers of

starlings and rabbits (Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003).

The remoteness, location, limited resources and harsh

environment have provided the area a high degree

of natural protection. The area of the site has been

increased through a series of extensions, as “minor

boundary modifications”, in 1989, 2010, 2012 and 2013,

which has provided the property an extra layer of

protection. According to the State of Conservation

Report of 2021, a tourism master plan is being

developed that will provide guide policies and increase

the range of tourism-related experiences available to

visitors. According to the State of Conservation Report

of 2018, the management of the park is effective

and is perpetuating the values of the park. Threats

faced in some areas such as the sea level rise and

effects of climate change cannot be controlled by the

management (IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2020)

The monitoring and evaluation of the property

for adaptive management is mostly effective, and it

commits to providing regular reports of TWWHA (IUCN

World Heritage Outlook 2020).

In December 2016, a new management plan was

implemented under Tasmania’s Nature Conservation

Act 2002. The new management plan includes banning

of logging and mining activities inside the property, and

it facilitates joint management arrangements with the

Tasmanian aboriginal people to support and improve

their cultural heritage values (IUCN World Heritage

Outlook 2020).

The Aboriginal Heritage Council provides advice and

guides the development of the plan to carry out an

assessment of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage

Site. The State party states about appointing the

specific reserve zone for Permanent Timber Production

Zone Land (PTPZL) and Future Potential Production

Forest Land (FPPFL) upon community consultation.

The Committee requests the state party to speed the

process of designation (State of Conservation Report

of 2021). Funds to the tune of AUD 3.2 million (USD

2.5 million) have been released for the protection of

the endangered orange-bellied parrots (Neophema

chrysogaster) (State of Conservation Report of 2018).