Sundarbans National Park (452)

Sundarbans National Park is the second largest biosphere reserve of India, and it is the largest mangrove forest of the world. The ecosystem of the Sunderban is highly productive, and it supports a diverse flora and fauna. It also bears international status as a biosphere reserve under the UNESCO's Man and Biosphere Program. Almost half the area is covered by water (45%), and the remaining is the terrestrial area (55%). The park is also home to many endangered species such as the Ganges dolphin, Irrawady dolphin, hump-backed dolphin, river terrapin, olive ridley turtle and estuarine crocodile. Various water birds and waders are seen in the park. The park gets a high level of protection from various laws of the Indian Government. The management of the park is mostly effective, and the property is well maintained and in a good state of conservation. According to an assessment by the IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2020, the property falls under the category of "Good with Some Concern". However, the property is facing numerous current and potential threats that could affect its outstanding universal values if not addressed soon. These threats include alien invasions, oil spills and climate change.

Sundarbans National Park is the second largest biosphere reserve of India, and it is the largest mangrove forest of the world. The ecosystem of the Sunderban is highly productive, and it supports a diverse flora and fauna. It also bears international status as a biosphere reserve under the UNESCO's Man and Biosphere Program. Almost half the area is covered by water (45%), and the remaining is the terrestrial area (55%). The park is also home to many endangered species such as the Ganges dolphin, Irrawady dolphin, hump-backed dolphin, river terrapin, olive ridley turtle and estuarine crocodile. Various water birds and waders are seen in the park. The park gets a high level of protection from various laws of the Indian Government. The management of the park is mostly effective, and the property is well maintained and in a good state of conservation. According to an assessment by the IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2020, the property falls under the category of "Good with Some Concern". However, the property is facing numerous current and potential threats that could affect its outstanding universal values if not addressed soon. These threats include alien invasions, oil spills and climate change.

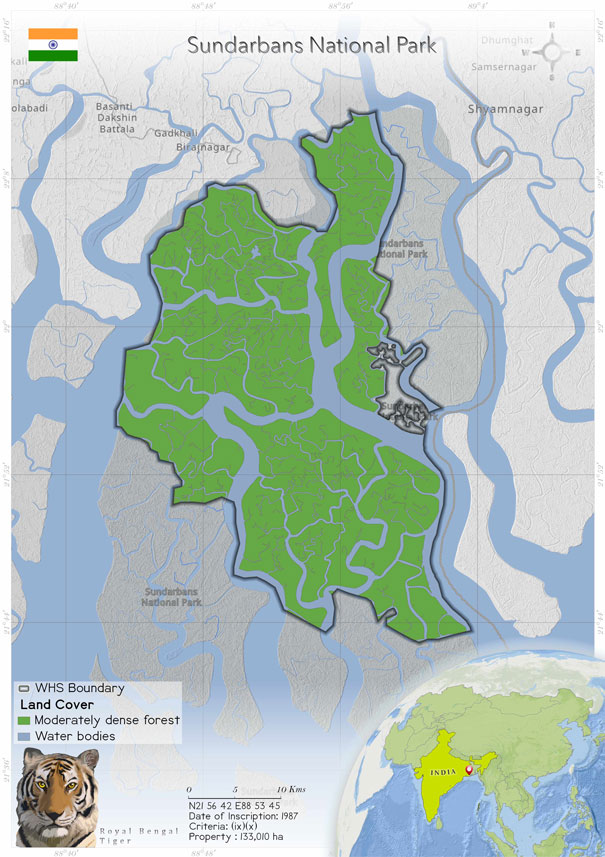

Sundarbans National Park is situated at the delta of the Ganga and Brahmaputra rivers and is spread across India and Bangladesh. This ecosystem is highly productive, with dynamic interactions between the land and water (Gupta & Sarkar 2014). Its terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems support a diverse array of plants and animals that are highly threatened. The tigers of the Sunderban have a unique identity as they have adapted to an amphibious lifestyle (UNESCO whc.unesco.org). They have adjusted themselves to the saline and watery environment (Tiwari 2011), and they can swim in the water and hunt for prey like fishes, crabs and water monitor lizards (UNESCO whc.unesco.org).

Bangladesh lies to the east of the property, with the Harinhanga, Raimangal and Kalindi rivers separating it into two nations. The west of the park is bounded by the Matla River and the south by the Bay of Bengal (Brahma et al. 2008). There are three wildlife sanctuaries in the property, which act as a buffer zone. In November 2001, the site was declared a biosphere reserve under the UNESCO's Man and Biosphere Program (Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003). It is the second-largest biosphere reserve of India, conserving coastal mangrove (Brahma et al. 2008). The park includes around 100 islands created by its tidal rivers, estuaries and creeks (Bose 2009).

The mangrove forests act as a barrier for storms: they are shore stabilizers and nutrient and sediment traps (UNESCO whc.unesco.org); but at the same time, the area is also recognized as vulnerable to tropical cyclones, storm surges, land subsidence, the sea-level rise, coastal erosion and coastal inundation (Dey et al. 2016). The tidal waves are seen regularly, rising up to 75 m high (World Heritage Nomination -- IUCN Summary 1987). Ecological processes such as monsoon rain flooding, delta formation, tidal influences and plant colonization can be studied at the site. 45% of the total land is occupied by wetlands, which include tidal rivers, creeks, canals, vast estuaries (UNESCO whc.unesco.org), low-lying alluvial islands and mud banks, with sandy beaches and dunes along the coast (World Heritage Nomination -- IUCN Summary 1987). The remaining 55% is terrestrial land (UNESCO whc.unesco.org).

Protection of Sundarban National Park in India began in 1878. In 1977, it was declared a wildlife sanctuary, and it was recognized as a national park in 1984. The park receives protection from the Indian Forest Act and the Wildlife Protection Act (1972) (World Heritage Nomination -- IUCN Summary 1987).

Four types of forest are present in the Sundarban: saltwater forest, beach forest, low mangroves and sand dune vegetation (World Heritage Nomination -- IUCN Summary 1987). The mangrove forest is dominated by the family Rhizophoraceae (eight species). Cericops decandra had the highest frequency, at 73%, and Cericops tagal had the lowest frequency, 9% (Brahma et al. 2008).

In the lower Bengal Basin, Sunderban National Park is the only remaining natural habitat for the wide variety of animal species. In 1987, the Sundarban had the largest number of tigers in India, i.e., 264. The aquatic animals found in the waters of the Sundarban include the Ganges dolphin, Irrawaddy dolphin, hump-backed dolphin and finless porpoise. The reptiles found in the park include the river terrapin, olive ridley turtle and estuarine crocodile. The Sajnakhali area of the park hosts a wide variety of water birds, such as the black-necked stork, greater adjutant stork and openbill stork. The wader species found in the park include the Asian dowitcher, a rare winter migrant (World Heritage Nomination -- IUCN Summary 1987).

The property is located at an altitude of 0–10 m. The average rainfall recorded in the park is 175 cm. The temperature ranges from 2°C to 38°C (Tiwari 2011).

Sundarbans National Park is situated at the delta of the Ganga and Brahmaputra rivers and is spread across India and Bangladesh. This ecosystem is highly productive, with dynamic interactions between the land and water (Gupta & Sarkar 2014). Its terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems support a diverse array of plants and animals that are highly threatened. The tigers of the Sunderban have a unique identity as they have adapted to an amphibious lifestyle (UNESCO whc.unesco.org). They have adjusted themselves to the saline and watery environment (Tiwari 2011), and they can swim in the water and hunt for prey like fishes, crabs and water monitor lizards (UNESCO whc.unesco.org).

Bangladesh lies to the east of the property, with the Harinhanga, Raimangal and Kalindi rivers separating it into two nations. The west of the park is bounded by the Matla River and the south by the Bay of Bengal (Brahma et al. 2008). There are three wildlife sanctuaries in the property, which act as a buffer zone. In November 2001, the site was declared a biosphere reserve under the UNESCO's Man and Biosphere Program (Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003). It is the second-largest biosphere reserve of India, conserving coastal mangrove (Brahma et al. 2008). The park includes around 100 islands created by its tidal rivers, estuaries and creeks (Bose 2009).

The mangrove forests act as a barrier for storms: they are shore stabilizers and nutrient and sediment traps (UNESCO whc.unesco.org); but at the same time, the area is also recognized as vulnerable to tropical cyclones, storm surges, land subsidence, the sea-level rise, coastal erosion and coastal inundation (Dey et al. 2016). The tidal waves are seen regularly, rising up to 75 m high (World Heritage Nomination -- IUCN Summary 1987). Ecological processes such as monsoon rain flooding, delta formation, tidal influences and plant colonization can be studied at the site. 45% of the total land is occupied by wetlands, which include tidal rivers, creeks, canals, vast estuaries (UNESCO whc.unesco.org), low-lying alluvial islands and mud banks, with sandy beaches and dunes along the coast (World Heritage Nomination -- IUCN Summary 1987). The remaining 55% is terrestrial land (UNESCO whc.unesco.org).

Protection of Sundarban National Park in India began in 1878. In 1977, it was declared a wildlife sanctuary, and it was recognized as a national park in 1984. The park receives protection from the Indian Forest Act and the Wildlife Protection Act (1972) (World Heritage Nomination -- IUCN Summary 1987).

Four types of forest are present in the Sundarban: saltwater forest, beach forest, low mangroves and sand dune vegetation (World Heritage Nomination -- IUCN Summary 1987). The mangrove forest is dominated by the family Rhizophoraceae (eight species). Cericops decandra had the highest frequency, at 73%, and Cericops tagal had the lowest frequency, 9% (Brahma et al. 2008).

In the lower Bengal Basin, Sunderban National Park is the only remaining natural habitat for the wide variety of animal species. In 1987, the Sundarban had the largest number of tigers in India, i.e., 264. The aquatic animals found in the waters of the Sundarban include the Ganges dolphin, Irrawaddy dolphin, hump-backed dolphin and finless porpoise. The reptiles found in the park include the river terrapin, olive ridley turtle and estuarine crocodile. The Sajnakhali area of the park hosts a wide variety of water birds, such as the black-necked stork, greater adjutant stork and openbill stork. The wader species found in the park include the Asian dowitcher, a rare winter migrant (World Heritage Nomination -- IUCN Summary 1987).

The property is located at an altitude of 0–10 m. The average rainfall recorded in the park is 175 cm. The temperature ranges from 2°C to 38°C (Tiwari 2011).

Criterion (ix)

The Sundarbans is the largest area of mangrove forest in the world and the only one that is inhabited by the tiger. The land area in the Sundarbans is constantly being changed, moulded and shaped by the action of the tides, with erosion processes more prominent along estuaries and deposition processes along the banks of inner estuarine waterways influenced by the accelerated discharge of silt from sea water. Its role as a wetland nursery for marine organisms and as a climatic buffer against cyclones is a unique natural process.

The Sundarbans is the largest area of mangrove forest in the world and the only one that is inhabited by the tiger. The land area in the Sundarbans is constantly being changed, moulded and shaped by the action of the tides, with erosion processes more prominent along estuaries and deposition processes along the banks of inner estuarine waterways influenced by the accelerated discharge of silt from sea water. Its role as a wetland nursery for marine organisms and as a climatic buffer against cyclones is a unique natural process.

Criterion (x)

The mangrove ecosystem of the Sundarbans is considered to be unique because of its immensely rich mangrove flora and mangrove-associated fauna. Some 78 species of mangroves have been recorded in the area making it the richest mangrove forest in the world. It is also unique as the mangroves are not only dominant as fringing mangroves along the creeks and backwaters, but also grow along the sides of rivers in muddy as well as in flat, sandy areas.

Status

Laws passed by the Indian Government such as the Indian Forest Act, 1927, with its amendments, the Forest Conservation Act, 1980, the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 and the Environment Protection Act, 1986 provides the highest level of protection to the property (UNESCO whc.unesco.org). Other laws that applies to the property are the Bengal Amendment of the Indian Forest Act (1988); the Fisheries Act of the West Bengal Government; and the Coastal and Regulatory Zone Rules (Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003). The management has an approved management plan, and the property is under regular monitoring.

For more effective management, the forest department is working hard to improve the financial and human resources of the property. The assessment done in the Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003 reports that the park needs around 100 forest guards to maintain the field camps. The local communities around the national park depend on the forest for many basic needs. Thus, an alternative livelihood source should be provided to the people. This will decrease their dependence on the forest (UNESCO whc.unesco.org). The activities on which the local people rely are the honey collection, crab, prawn collection, fishing and fuel wood collection. The crab collection and crab-fattening business contribute the most to the local economy. Ecotourism is also considered a cultural service that contributes to the economy (Basu et al. 2017).

The management of the property is mostly effective as reported by the IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2020. The tiger conservation plan serve as a road map for management planning. Coordinated joint patrolling is conducted in the park by the forest department and the Border Security Force (BSF). This implies that the universal values of the site are intact due to efficient protection and management (IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2020).

Tourism is allowed in the buffer zone of the park, and 40,000 tourists are expected to visit every year. Ten Forest Protection Committees and 14 Eco Development Committees have been formed in the Sunderban, and many eco-development activities takes place with the help of these committees, such as construction of irrigation channels, ponds, tube wells, paths and jetties; development of fish and crab culture facilities; provision of solar power; establishment of medical camps; and vocational training (State of Conservation Report 2002).

The Sunderban is facing an invasion of Laevicaulis haroldi, which is also called the caterpillar slug (Sreeraj 2020). The Sagar Islands, where agriculture is the main occupation, is facing an invasion of Lissachatina fulica, an alien crop pest (Sajan et al. 2018) that can cause damage to the agriculture and in turn the economy. Thus studies and research on the distribution and eradication of this species are needed. The most menacing threat to the property is the rise in the sea level. which is 3.14 mm per year. The islands and mangroves are submerging as a result (Bose 2009). The increases in the sea level and average rainfall, increased cyclone activity and increase in the sea surface temperature are all indicators of climate change (Gupta & Sarkar 2014).

The threats to the property include the increase in the human population, poverty and unemployment (Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003). The reduction in the forest cover is increasing day by day as the forest is getting converted into villages and the people of the village are cutting down the tree unknowingly. Tourism is also increasing inside the buffer zone if the property. It was recorded that during 1990–2002 the annual number of visitors increased from 22,049 to 34,011 (Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003). Many afforestation programmes have been conducted in the park since 1989 for maintaining the biodiversity. It is suggested that awareness programmes and Forest Protection Programmes be conducted for the local communities (Brahma et al. 2008).

Laws passed by the Indian Government such as the Indian Forest Act, 1927, with its amendments, the Forest Conservation Act, 1980, the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 and the Environment Protection Act, 1986 provides the highest level of protection to the property (UNESCO whc.unesco.org). Other laws that applies to the property are the Bengal Amendment of the Indian Forest Act (1988); the Fisheries Act of the West Bengal Government; and the Coastal and Regulatory Zone Rules (Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003). The management has an approved management plan, and the property is under regular monitoring.

For more effective management, the forest department is working hard to improve the financial and human resources of the property. The assessment done in the Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003 reports that the park needs around 100 forest guards to maintain the field camps. The local communities around the national park depend on the forest for many basic needs. Thus, an alternative livelihood source should be provided to the people. This will decrease their dependence on the forest (UNESCO whc.unesco.org). The activities on which the local people rely are the honey collection, crab, prawn collection, fishing and fuel wood collection. The crab collection and crab-fattening business contribute the most to the local economy. Ecotourism is also considered a cultural service that contributes to the economy (Basu et al. 2017).

The management of the property is mostly effective as reported by the IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2020. The tiger conservation plan serve as a road map for management planning. Coordinated joint patrolling is conducted in the park by the forest department and the Border Security Force (BSF). This implies that the universal values of the site are intact due to efficient protection and management (IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2020).

Tourism is allowed in the buffer zone of the park, and 40,000 tourists are expected to visit every year. Ten Forest Protection Committees and 14 Eco Development Committees have been formed in the Sunderban, and many eco-development activities takes place with the help of these committees, such as construction of irrigation channels, ponds, tube wells, paths and jetties; development of fish and crab culture facilities; provision of solar power; establishment of medical camps; and vocational training (State of Conservation Report 2002).

The Sunderban is facing an invasion of Laevicaulis haroldi, which is also called the caterpillar slug (Sreeraj 2020). The Sagar Islands, where agriculture is the main occupation, is facing an invasion of Lissachatina fulica, an alien crop pest (Sajan et al. 2018) that can cause damage to the agriculture and in turn the economy. Thus studies and research on the distribution and eradication of this species are needed. The most menacing threat to the property is the rise in the sea level. which is 3.14 mm per year. The islands and mangroves are submerging as a result (Bose 2009). The increases in the sea level and average rainfall, increased cyclone activity and increase in the sea surface temperature are all indicators of climate change (Gupta & Sarkar 2014).

The threats to the property include the increase in the human population, poverty and unemployment (Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003). The reduction in the forest cover is increasing day by day as the forest is getting converted into villages and the people of the village are cutting down the tree unknowingly. Tourism is also increasing inside the buffer zone if the property. It was recorded that during 1990–2002 the annual number of visitors increased from 22,049 to 34,011 (Periodic Reporting Cycle 2003). Many afforestation programmes have been conducted in the park since 1989 for maintaining the biodiversity. It is suggested that awareness programmes and Forest Protection Programmes be conducted for the local communities (Brahma et al. 2008).