Shirakami-Sanchi (663)

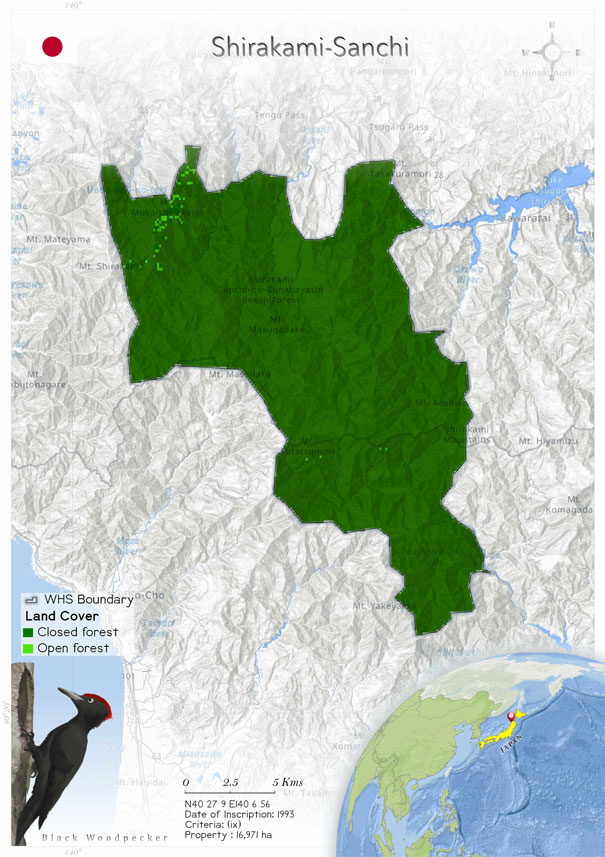

Shirakami-Sanchi was inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 1993. The property is situated at the northern hill of Honshu, Japan, with an area of 16,971 ha. The site's scenic beauty drives from a landscape of deciduous forests. The site also forms the habitat of many species including eighty-seven bird species, of which the black woodpecker is one, large mammals, such as the Japanese serow and Japanese black bear, and endemic species such as Fagus crenata, and Sasa kurilensis. The site is classified by unique characteristics that define its current pristine conditions, with the assumption that its origins lie in the form of circumpolar vegetation prior to the Last Glacial Stage, with beech forests transiting from the circumpolar region to the south during the Last Glacial Stage. Although in innumerable arenas, the mountainous areas stretching East to West blocked the shifts. However, the site has a chain of climax forests that retain circumpolar diversity and elements of the Arco-Tertiary Geoflora. The management actions have been able to generate stability over the region in general. However, there remain a series of potential threats, such as climate change and the rise of overabundant species that can alter the ecological integrity of the site. Presently, the government has remained an active player at both the national and local levels to safeguard and manage the site.

Shirakami-Sanchi was inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 1993. The property is situated at the northern hill of Honshu, Japan, with an area of 16,971 ha. The site's scenic beauty drives from a landscape of deciduous forests. The site also forms the habitat of many species including eighty-seven bird species, of which the black woodpecker is one, large mammals, such as the Japanese serow and Japanese black bear, and endemic species such as Fagus crenata, and Sasa kurilensis. The site is classified by unique characteristics that define its current pristine conditions, with the assumption that its origins lie in the form of circumpolar vegetation prior to the Last Glacial Stage, with beech forests transiting from the circumpolar region to the south during the Last Glacial Stage. Although in innumerable arenas, the mountainous areas stretching East to West blocked the shifts. However, the site has a chain of climax forests that retain circumpolar diversity and elements of the Arco-Tertiary Geoflora. The management actions have been able to generate stability over the region in general. However, there remain a series of potential threats, such as climate change and the rise of overabundant species that can alter the ecological integrity of the site. Presently, the government has remained an active player at both the national and local levels to safeguard and manage the site.

Shirakami-Sanchi is located near the northern Honshu Sea (Pacific Ocean) (Knörr et al. 2012), at an elevation of 100-1234 m above sea level (140° 07' E, 40° 28' N). The site has an area of 16,971 ha and was registered as a World Heritage Site in 1993. The physiography of Shirakami-Sanchi is characterized by the presence of a broad-leaved deciduous forest area with a sea-type climate, with snowfall during winters (Teodoridis et al. 2011), and cool-temperate beech forests that have blanketed the hills and mountain slopes of northern Japan for an extended period of time (8000-12,000 years). The beech forests cover one-third of the mountain range with the most significant remaining virgin beech forest in East Asia. This forest has Siebold’s beech trees. The pristine climax forest has survived the ice age. The site has not experienced a shift in its distribution as it has remained fundamentally undisturbed. Such a condition is rarely observed in East Africa. The range and composition of the pristine forests, which have not suffered developmental impacts, stimulates the diverse trend from the heavily compact with dense population, long inhabited Japan across Asia (IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2020).

Shirakami-Sanchi is located near the northern Honshu Sea (Pacific Ocean) (Knörr et al. 2012), at an elevation of 100-1234 m above sea level (140° 07' E, 40° 28' N). The site has an area of 16,971 ha and was registered as a World Heritage Site in 1993. The physiography of Shirakami-Sanchi is characterized by the presence of a broad-leaved deciduous forest area with a sea-type climate, with snowfall during winters (Teodoridis et al. 2011), and cool-temperate beech forests that have blanketed the hills and mountain slopes of northern Japan for an extended period of time (8000-12,000 years). The beech forests cover one-third of the mountain range with the most significant remaining virgin beech forest in East Asia. This forest has Siebold’s beech trees. The pristine climax forest has survived the ice age. The site has not experienced a shift in its distribution as it has remained fundamentally undisturbed. Such a condition is rarely observed in East Africa. The range and composition of the pristine forests, which have not suffered developmental impacts, stimulates the diverse trend from the heavily compact with dense population, long inhabited Japan across Asia (IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2020).

Criterion (ix)

Shirakami-Sanchi is dominated by beech accompanied by diverse vegetation that escaped simplification during the earth’s glacial stages by shifting its distribution towards the south, resulting in a virtually undisturbed, pristine climax wilderness forest. The property covers approximately one third of the Shirakami mountain range and comprises a maze of steep sided hills and summits. The undisturbed wilderness condition of the area is wild and rare in eastern Asia with no other protected area in Japan containing a large unmodified beech forest like that found in the property. The extent of its pristine forest without extrinsic development sets the property apart in densely populated, long-inhabited Japan and across Asia.

The property is the last and best relic of the cool-temperate beech forests that once covered northern Japan. A member of the genus dominated in cool-temperate forests in the northern hemisphere, Siebold’s beech (Fagus crenata) comprises the mono-specific canopy and the forest contains the main species of the ecosystem including black woodpecker (Dryocopus martius), Japan serow (Capricornis crispus), Japanese black bear (Ursus thibetanus japonicas), Japanese macaque (Macaca fuscata) and dwarf bamboo (Sasa kurilensis). The forest ecosystem reflects the history of global climate changes and the heavy-snow environment, and is an outstanding process in the development and succession of communities of plants together with animal groups that depend on them. The property is very essential for the studies on terrestrial cool-temperate ecology, particularly in Eurasian beech forest ecosystem processes, and for long term monitoring of the climate and vegetation changes.

Shirakami-Sanchi is dominated by beech accompanied by diverse vegetation that escaped simplification during the earth’s glacial stages by shifting its distribution towards the south, resulting in a virtually undisturbed, pristine climax wilderness forest. The property covers approximately one third of the Shirakami mountain range and comprises a maze of steep sided hills and summits. The undisturbed wilderness condition of the area is wild and rare in eastern Asia with no other protected area in Japan containing a large unmodified beech forest like that found in the property. The extent of its pristine forest without extrinsic development sets the property apart in densely populated, long-inhabited Japan and across Asia.

The property is the last and best relic of the cool-temperate beech forests that once covered northern Japan. A member of the genus dominated in cool-temperate forests in the northern hemisphere, Siebold’s beech (Fagus crenata) comprises the mono-specific canopy and the forest contains the main species of the ecosystem including black woodpecker (Dryocopus martius), Japan serow (Capricornis crispus), Japanese black bear (Ursus thibetanus japonicas), Japanese macaque (Macaca fuscata) and dwarf bamboo (Sasa kurilensis). The forest ecosystem reflects the history of global climate changes and the heavy-snow environment, and is an outstanding process in the development and succession of communities of plants together with animal groups that depend on them. The property is very essential for the studies on terrestrial cool-temperate ecology, particularly in Eurasian beech forest ecosystem processes, and for long term monitoring of the climate and vegetation changes.

Status

The property of Shirakami-Sanchi is a national forest and is managed by the National Government. The various agencies responsible for protecting the forests include the Ministry of the Environment, the Forestry Agency, the Agency for Cultural Affairs and other municipal authorities.

The legal framework protecting the environment of the Shirakami-Sanchi includes the Natural Conservation Law of the Ministry of Environment (looks over the management of National Parks and Nature Conservation Areas), the Act of Administration and Management of National Forest (1951) and the National Forest Administration and Management Bylaw (1999) managed and protected by the ecosystem reserve. The Ministry of Environment (2013) reports that the management plan has been updated. It focuses on promoting and sustaining the efficient, effective and integrated cooperation with the local municipalities (Ajigasawa-machi, Fukaura-machi, and Happo-cho in Akita Prefecture) for further development and use (UNESCO whc.unesco.org).

According to the State of Conservation Report 1995 the logging around the contiguous forests in the mid-1990s was heightened. The tourism has reduced over time and has been decreasing since 2000–2006 (IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2017). Potential threats include risks such as climate change, which is capable of impacting the temperature and snowfall patterns, which might result in a change in the ecological diversity. The threat caused by the entry of sika deer into the property has been growing stronger. An increasing population could pose a severe challenge due to the absence of wolves in many parts of Japan, which may result in severe damage to the existing vegetation. Though the population has not yet expanded to the site, its spread in the adjoining areas could pose a severe challenge to the vegetation of the site (IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2017). Researchers concede that there existed a harmonious relationship between the local people and the government when the property was established. Increasingly, local people are dissatisfied due to the absence of shared benefits from the site. The tourism is limited by management controls, and the opportunities are very limited on the mainly trackless and undisturbed property (IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2014).

It must be noted that the overall values of the World Heritage Site have been protected well by strengthening the regulations, legislation and effective management of the site. The pristine conditions of the forests are well-maintained by the authorities, but the potential threats must be managed effectively. Otherwise, they can cause severe problems to the ecology of the region.

The property of Shirakami-Sanchi is a national forest and is managed by the National Government. The various agencies responsible for protecting the forests include the Ministry of the Environment, the Forestry Agency, the Agency for Cultural Affairs and other municipal authorities.

The legal framework protecting the environment of the Shirakami-Sanchi includes the Natural Conservation Law of the Ministry of Environment (looks over the management of National Parks and Nature Conservation Areas), the Act of Administration and Management of National Forest (1951) and the National Forest Administration and Management Bylaw (1999) managed and protected by the ecosystem reserve. The Ministry of Environment (2013) reports that the management plan has been updated. It focuses on promoting and sustaining the efficient, effective and integrated cooperation with the local municipalities (Ajigasawa-machi, Fukaura-machi, and Happo-cho in Akita Prefecture) for further development and use (UNESCO whc.unesco.org).

According to the State of Conservation Report 1995 the logging around the contiguous forests in the mid-1990s was heightened. The tourism has reduced over time and has been decreasing since 2000–2006 (IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2017). Potential threats include risks such as climate change, which is capable of impacting the temperature and snowfall patterns, which might result in a change in the ecological diversity. The threat caused by the entry of sika deer into the property has been growing stronger. An increasing population could pose a severe challenge due to the absence of wolves in many parts of Japan, which may result in severe damage to the existing vegetation. Though the population has not yet expanded to the site, its spread in the adjoining areas could pose a severe challenge to the vegetation of the site (IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2017). Researchers concede that there existed a harmonious relationship between the local people and the government when the property was established. Increasingly, local people are dissatisfied due to the absence of shared benefits from the site. The tourism is limited by management controls, and the opportunities are very limited on the mainly trackless and undisturbed property (IUCN World Heritage Outlook 2014).

It must be noted that the overall values of the World Heritage Site have been protected well by strengthening the regulations, legislation and effective management of the site. The pristine conditions of the forests are well-maintained by the authorities, but the potential threats must be managed effectively. Otherwise, they can cause severe problems to the ecology of the region.