Sagarmatha National Park (120)

Sagarmatha National Park (SNP), the world’s highest national park, established in 1976, spreads over an area of 124,400 ha and lies in the Solu-Khumbu region of Nepal. The national park comprises of multiple magnificent snow-capped peaks, gorges, glaciers and Mt. Everest, world’s highest peak (8,848 m). The site shares an international border with Qomolangma National Nature Preserve of Tibet, in the north. It is adjacent to Makalu Barun National Park, in the east, extending to the Dudh Kosi River, in the south. It is home to rare animals such as the snow leopard (Panthera uncia) and the lesser or red panda (Ailurus fulgens) and of thousands of plants. The national park has become quite a popular location for eco-tourism, and it has flourished immensely. But excessive tourism has exhausted the national park’s ecosystem, and this has been a concern for conservationists and the SNP authority. The establishment of parks such as Makalu Barun National Park (1998), in the east, and Gauri Shankar Conservation Area (2010), in the west, provide the park additional protection. Another protective measure taken by the government is the initiation of the Sacred Himalayan Landscape (SHL) conservation and management programme. The national park also has Gokyo Lake, which was designated a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar Convention.

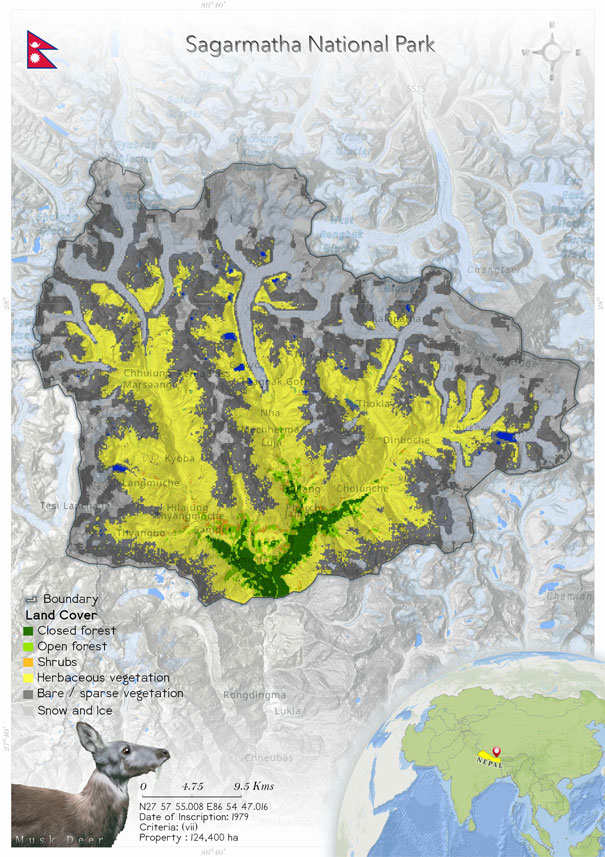

Sagarmatha National Park (SNP), the world’s highest national park, established in 1976, spreads over an area of 124,400 ha and lies in the Solu-Khumbu region of Nepal. The national park comprises of multiple magnificent snow-capped peaks, gorges, glaciers and Mt. Everest, world’s highest peak (8,848 m). The site shares an international border with Qomolangma National Nature Preserve of Tibet, in the north. It is adjacent to Makalu Barun National Park, in the east, extending to the Dudh Kosi River, in the south. It is home to rare animals such as the snow leopard (Panthera uncia) and the lesser or red panda (Ailurus fulgens) and of thousands of plants. The national park has become quite a popular location for eco-tourism, and it has flourished immensely. But excessive tourism has exhausted the national park’s ecosystem, and this has been a concern for conservationists and the SNP authority. The establishment of parks such as Makalu Barun National Park (1998), in the east, and Gauri Shankar Conservation Area (2010), in the west, provide the park additional protection. Another protective measure taken by the government is the initiation of the Sacred Himalayan Landscape (SHL) conservation and management programme. The national park also has Gokyo Lake, which was designated a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar Convention.

Sagarmatha National Park is Nepal’s first national park to be inscribed as a World Heritage Site. The site is situated in the north-eastern part of Nepal along the international border with the Tibetan Autonomous Region of China, in the upper catchment of the Dudh Kosi River. It is located between latitudes 27? 46' 19" and 27? 06' 45" N and longitudes 86? 30' 53" and 86? 99' 08" E (Shah et al. 2019). The Dudh Kosi River flows through the park, which also includes the upper catchment areas of the Bhotekoshi river basin and the Gokyo Lakes. Sagarmatha has an extent of 1148 km2 (443 square miles) and a buffer zone of 275 km2, including the settlements inside. The site is surrounded by 25 or more peaks, including Baruntse, Lhotse, Nuptse, Pumo Ri, Guachung Kang, Cho-Oyu and Nangpai Gosum (over 7000m high). The mountain range of the national park is geologically young, formed only about 50 million years back, after the convergence of the Indian and Asian tectonic plates (World Heritage Datasheet). Above 16,000 ft., 69% of the park is barren land, while 28% is grazing land and 3% is forested. The climatic zones of the site are the forested temperate zone, the subalpine zone, above 3000 m (9800 feet), and the alpine zone, above 4000 m, that represents the upper limit of vegetation. The nival zone starts at a height of 5000 m (Bhuju et al. 2007). Firs, the Himalayan birch, rhododendrons, and junipers are a few floral species that one can find at the site. The national park was also declared an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International in 2008. The site is home to more than 150 bird species, including high altitude breeding species, such as the blood pheasant (Ithaginis cruentus), white-throated redstart (Phoenicurus schisticeps) and rosefinches, as well as different aquatic birds such as the ferruginous duck (Aythya nyroca) and the demoiselle crane (Grus virgo). The lakes of the national parks are also serve as a host for different migrating birds. The park is also the home of several mammal species such as the snow leopard (Panthera uncia), the lesser or red panda (Ailurus fulgens), the Himalayan black bear (Ursus thibetanus) and the Himalayan musk deer (Moschus leucogaster). The Sherpas are another vital part of the national park, and according to A. Byers (2005), about 3,500 Sherpa people live in the national park.

The vegetation zones of Sagarmatha was described by Dobremez (1975), who identified six of them. These are the lower sub-alpine (3000m and above), upper sub-alpine (3600m and above), lower alpine (3800–4000m), upper alpine (4500 m and above), and sub-nival zones. The park is dominated by firs, the Himalayan birch, rhododendrons and junipers. Mosses and lichens can be found above 5000 m too. The mountains of Sagarmatha are very sacred to the Sherpas, who attach a religious value to them. The Sherpas have lived on the mountains for centuries, and their culture and the natural heritage of Sagarmatha are beautifully and intricately woven together. Their traditional practices and indigenous natural resource management practices have been major contributing factors to the successful conservation of SNP.

Sagarmatha National Park is Nepal’s first national park to be inscribed as a World Heritage Site. The site is situated in the north-eastern part of Nepal along the international border with the Tibetan Autonomous Region of China, in the upper catchment of the Dudh Kosi River. It is located between latitudes 27? 46' 19" and 27? 06' 45" N and longitudes 86? 30' 53" and 86? 99' 08" E (Shah et al. 2019). The Dudh Kosi River flows through the park, which also includes the upper catchment areas of the Bhotekoshi river basin and the Gokyo Lakes. Sagarmatha has an extent of 1148 km2 (443 square miles) and a buffer zone of 275 km2, including the settlements inside. The site is surrounded by 25 or more peaks, including Baruntse, Lhotse, Nuptse, Pumo Ri, Guachung Kang, Cho-Oyu and Nangpai Gosum (over 7000m high). The mountain range of the national park is geologically young, formed only about 50 million years back, after the convergence of the Indian and Asian tectonic plates (World Heritage Datasheet). Above 16,000 ft., 69% of the park is barren land, while 28% is grazing land and 3% is forested. The climatic zones of the site are the forested temperate zone, the subalpine zone, above 3000 m (9800 feet), and the alpine zone, above 4000 m, that represents the upper limit of vegetation. The nival zone starts at a height of 5000 m (Bhuju et al. 2007). Firs, the Himalayan birch, rhododendrons, and junipers are a few floral species that one can find at the site. The national park was also declared an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International in 2008. The site is home to more than 150 bird species, including high altitude breeding species, such as the blood pheasant (Ithaginis cruentus), white-throated redstart (Phoenicurus schisticeps) and rosefinches, as well as different aquatic birds such as the ferruginous duck (Aythya nyroca) and the demoiselle crane (Grus virgo). The lakes of the national parks are also serve as a host for different migrating birds. The park is also the home of several mammal species such as the snow leopard (Panthera uncia), the lesser or red panda (Ailurus fulgens), the Himalayan black bear (Ursus thibetanus) and the Himalayan musk deer (Moschus leucogaster). The Sherpas are another vital part of the national park, and according to A. Byers (2005), about 3,500 Sherpa people live in the national park.

The vegetation zones of Sagarmatha was described by Dobremez (1975), who identified six of them. These are the lower sub-alpine (3000m and above), upper sub-alpine (3600m and above), lower alpine (3800–4000m), upper alpine (4500 m and above), and sub-nival zones. The park is dominated by firs, the Himalayan birch, rhododendrons and junipers. Mosses and lichens can be found above 5000 m too. The mountains of Sagarmatha are very sacred to the Sherpas, who attach a religious value to them. The Sherpas have lived on the mountains for centuries, and their culture and the natural heritage of Sagarmatha are beautifully and intricately woven together. Their traditional practices and indigenous natural resource management practices have been major contributing factors to the successful conservation of SNP.

Criterion (ix)

Sagarmatha National Parks’ superlative and exceptional natural beauty is embedded in the dramatic mountains, glaciers, deep valleys and majestic peaks including the Worlds’ highest, Mount Sagarmatha (Everest) (8,848 m.). The area is home to several rare species such as the snow leopard and the red panda. The area represents a major stage of the Earth’s evolutionary history and is one of the most geologically interesting regions in the world with high, geologically young mountains and glaciers creating awe inspiring landscapes and scenery dominated by the high peaks and corresponding deeply-incised valleys. This park contains the world’s highest ecologically characteristic flora and fauna, intricately blended with the rich Sherpa culture. The intricate linkages of the Sherpa culture with the ecosystem are a major highlight of the park and they form the basis for the sustainable protection and management of the park for the benefit of the local communities.

Sagarmatha National Parks’ superlative and exceptional natural beauty is embedded in the dramatic mountains, glaciers, deep valleys and majestic peaks including the Worlds’ highest, Mount Sagarmatha (Everest) (8,848 m.). The area is home to several rare species such as the snow leopard and the red panda. The area represents a major stage of the Earth’s evolutionary history and is one of the most geologically interesting regions in the world with high, geologically young mountains and glaciers creating awe inspiring landscapes and scenery dominated by the high peaks and corresponding deeply-incised valleys. This park contains the world’s highest ecologically characteristic flora and fauna, intricately blended with the rich Sherpa culture. The intricate linkages of the Sherpa culture with the ecosystem are a major highlight of the park and they form the basis for the sustainable protection and management of the park for the benefit of the local communities.

Status

Sagarmatha was designated a national park in 1976 under the type II national park conservation criteria, and in 1979 Sagarmatha National Park was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. The diversity of the flora and fauna, the unique Sherpa culture and the breathtaking scenic grandeur contribute to the outstanding universal significance of Sagarmatha and make it an iconic site. One of the earliest sites to be named a World Natural Heritage Site, it includes the majestic Himalayan range and Mount Everest, which is one of the main attractions of the national park. The number of expeditions to the world’s highest peak is ever-increasing, but sadly enough it has become the world’s highest “junk yard” (Bishop 1963). The visitor now stumbles upon old tents, used oxygen bottles, human waste, paper and other stuff left behind by previous ones (Bishop & Naumann 1996). An increase in the number of tourists and climbers was observed (3600 visitors in 1979 to over 25,000 in 2010), which boosted the local community economically and helped improve their standard of living (UNESCO). The property has been a World Heritage Site since 1979, but Baral et al. (2017) noted that very few visitors knew about the World Heritage status of SNP and out of all the visitors during the study a full quarter of them were not even aware about the World Heritage programme. Adventure tourism have led to overexploitation of the alpine landscapes, and the landscape is in dire need of conservation, protection and restoration (Byers 2005). Fortunately, a “community-based alpine conservation and restoration project” implemented by American Alpine Club in 2003 (Byers 2005; UIAA 2003; AAC 2004) and a council of locals named Alpine Conservation Council was launched in 2004 for the restoration and conservation of the alpine ecosystem (Byers 2016; Sherpa 2003, 2004).

The establishment of SNP resulted in a disagreement between the local communities and the officials. The formation of the national park incited the rights of local residing communities, which led to the turmoil, and in 2003 the Nepalese government was forced to develop a buffer zone around the national park (Stevens 2008). According to the doctoral thesis of Sherpa (2013), the administration of the park had been weaker than the past and lacked human resources. The park management was solely managed by the government, and no local communities were involved in decision making. The culture of the native Sherpa communities was endangered as the youth had no opportunity to serve within the park and were migrating out for their livelihoods. The patrolling and monitoring by the park authorities was not as effective as it should have been because a decline in the numbers of wild animals was observed and the park management failed to conduct scientific research to understand the reason behind the decline. The Sherpas regard wildlife, trees and other living possessions of the national park as sacred and had been conserving the national park in various ways for years (Sherpa 2013).

Many NGOs have come forward to protect the national park and foreign aid has been offered, but the efficacy of the foreign aid and NGOs needs to be evaluated. Bhatta and Bardecki (2014) showed that the foreign aid and aid from the NGOs was not properly accounted for. Their study focused on Sagarmatha National Park Forestry Project (SNPFP) and mentioned that the NGOs and foreign aid projects are deemed successful on paper because of a lack of evaluative studies. Bhatta and Bardecki’s (2014) study implied that the local stakeholders should be involved in the evaluation of such projects. And being the best source of information, the local community should be involved in conservation and development plans. Brower (1991) suggested that the amalgamation of westernized conservation methods with the traditional ways and the expertise of indigenous people will be much more effective for the protection and management of the national park.

The water of the national park acts as the source of the Ganges, Indus, Yangtze and other major river systems and is used by the local people living inside the site. The poor sanitization, letting sewage into nearby streams, dumping waste into water, etc. are increasing the water pollution. Nicholson et al. (2019) identified Escherichia coli and other coliform bacteria in the water of the national park. This study also found a correlation between precipitation and contamination of water, showing that high precipitation rates resulted in increased surface and spring water contamination.

An analysis of the previous State of Conservation (SoC) reports shows that the State Party is taking measures and is serious about conserving the Outstanding Universal Value of the site. The management plan of Sagarmatha National Park and its buffer zone (2016–2020) has been successfully implemented, and the officials are open to suggestions from the World Heritage Centre. The State Party is collaborating with the local stakeholders and the Nepali Army for the management of park. Law enforcement is also used in banning activities like collection of firewood. The authorities are financially, legally and technically aiding local institutions such as Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee (SPCC). SPCC is a local environmental institution that focuses on the waste management in the national park and its buffer zone. Their achievements have been exemplary. They were able to collect 10,000 kg of garbage from the Everest region and bring it to Kathmandu for processing. The World Heritage committee is concerned, and although it appreciates the efforts of the SPCC, it has suggested that the State Party cope with the ever-increasing solid and liquid waste, including the discard from hydropower plants. The State Party has been advised to incorporate adequate management practices in the management plan 2016–2020, including rules for using helicopters for transport and illegal firewood collection. The final verdict on the controversial Kongde View Resort has been given by the Nepali Supreme Court, and the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation (DNPWC) submitted it to the World Heritage Centre on 1 September 2019. As mentioned previously, climate change is one of the most serious challenges for the national park and might affect the Outstanding Universal Value of the site. Glacial hazards such as avalanches, debris flow, glacial fluctuations and glacial surges might be the immediate outcome of climate change in SNP. To overcome this situation, the DNPWC and the staff of the national park worked closely with the UNDP-funded “Community Based Flood and Glacial Lake Outburst Risk Reduction Project” and monitored the activities in the national park and its buffer zone. All the papers and documents of the project have also been given to the local communities. However, the information provided by the papers of the project does not clarify how local communities and their values can be integrated in the project and its management. An updated map of Sagarmatha National Park and its buffer zone has also been created. The park zonation is clearly visible now: the extent of the core zone is 1148 km2, and that of the buffer zone is 275 km2, including the settlements inside the park, as per the declaration in the Nepal Gazette regarding the buffer zone. The DNPWC and the park authority have proposed that the buffer zone of SNP be declared the buffer zone of the World Heritage Property, but the buffer zone management committee, the elected local bodies and local communities are not supporting this proposal. The environmental impact assessment (EIA) report was reviewed by the World Heritage Centre, and the DNPWC has asked Everest Link Pvt. Ltd. (concerned company) to incorporate the comments and recommendations made by the IUCN. The urbanization and development expectations of the people of Nepal and the new political transformations in Nepal are creating a huge problem for conservation, and climate change is not helping much. If development and conservation are not balanced, then there will be dire consequences for SNP and its Outstanding Universal Value.

The evaluation of the 2020 IUCN World Heritage Outlook showed that although the Outstanding Universal Significance of the park remains intact, the tourism, overexploitation of nature, development and pollution are compromising the world heritage value of SNP. In addition, climate change is also a concern for the high mountain ecosystem, the biodiversity and natural processes. A shortage of staff members and funding for the park’s management and maintenance are also affecting the SNP. The IUCN World Heritage Outlook suggests that international attention and scientific research might help address the threats to the World Heritage Site.

The inscription of Sagarmatha National Park in the World Heritage Site List has had an overall positive impact on the conservation of the majestic national park. The inscription has helped in policy making, management, research and other aspects of conserving the national park and its OUV.

Sagarmatha was designated a national park in 1976 under the type II national park conservation criteria, and in 1979 Sagarmatha National Park was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. The diversity of the flora and fauna, the unique Sherpa culture and the breathtaking scenic grandeur contribute to the outstanding universal significance of Sagarmatha and make it an iconic site. One of the earliest sites to be named a World Natural Heritage Site, it includes the majestic Himalayan range and Mount Everest, which is one of the main attractions of the national park. The number of expeditions to the world’s highest peak is ever-increasing, but sadly enough it has become the world’s highest “junk yard” (Bishop 1963). The visitor now stumbles upon old tents, used oxygen bottles, human waste, paper and other stuff left behind by previous ones (Bishop & Naumann 1996). An increase in the number of tourists and climbers was observed (3600 visitors in 1979 to over 25,000 in 2010), which boosted the local community economically and helped improve their standard of living (UNESCO). The property has been a World Heritage Site since 1979, but Baral et al. (2017) noted that very few visitors knew about the World Heritage status of SNP and out of all the visitors during the study a full quarter of them were not even aware about the World Heritage programme. Adventure tourism have led to overexploitation of the alpine landscapes, and the landscape is in dire need of conservation, protection and restoration (Byers 2005). Fortunately, a “community-based alpine conservation and restoration project” implemented by American Alpine Club in 2003 (Byers 2005; UIAA 2003; AAC 2004) and a council of locals named Alpine Conservation Council was launched in 2004 for the restoration and conservation of the alpine ecosystem (Byers 2016; Sherpa 2003, 2004).

The establishment of SNP resulted in a disagreement between the local communities and the officials. The formation of the national park incited the rights of local residing communities, which led to the turmoil, and in 2003 the Nepalese government was forced to develop a buffer zone around the national park (Stevens 2008). According to the doctoral thesis of Sherpa (2013), the administration of the park had been weaker than the past and lacked human resources. The park management was solely managed by the government, and no local communities were involved in decision making. The culture of the native Sherpa communities was endangered as the youth had no opportunity to serve within the park and were migrating out for their livelihoods. The patrolling and monitoring by the park authorities was not as effective as it should have been because a decline in the numbers of wild animals was observed and the park management failed to conduct scientific research to understand the reason behind the decline. The Sherpas regard wildlife, trees and other living possessions of the national park as sacred and had been conserving the national park in various ways for years (Sherpa 2013).

Many NGOs have come forward to protect the national park and foreign aid has been offered, but the efficacy of the foreign aid and NGOs needs to be evaluated. Bhatta and Bardecki (2014) showed that the foreign aid and aid from the NGOs was not properly accounted for. Their study focused on Sagarmatha National Park Forestry Project (SNPFP) and mentioned that the NGOs and foreign aid projects are deemed successful on paper because of a lack of evaluative studies. Bhatta and Bardecki’s (2014) study implied that the local stakeholders should be involved in the evaluation of such projects. And being the best source of information, the local community should be involved in conservation and development plans. Brower (1991) suggested that the amalgamation of westernized conservation methods with the traditional ways and the expertise of indigenous people will be much more effective for the protection and management of the national park.

The water of the national park acts as the source of the Ganges, Indus, Yangtze and other major river systems and is used by the local people living inside the site. The poor sanitization, letting sewage into nearby streams, dumping waste into water, etc. are increasing the water pollution. Nicholson et al. (2019) identified Escherichia coli and other coliform bacteria in the water of the national park. This study also found a correlation between precipitation and contamination of water, showing that high precipitation rates resulted in increased surface and spring water contamination.

An analysis of the previous State of Conservation (SoC) reports shows that the State Party is taking measures and is serious about conserving the Outstanding Universal Value of the site. The management plan of Sagarmatha National Park and its buffer zone (2016–2020) has been successfully implemented, and the officials are open to suggestions from the World Heritage Centre. The State Party is collaborating with the local stakeholders and the Nepali Army for the management of park. Law enforcement is also used in banning activities like collection of firewood. The authorities are financially, legally and technically aiding local institutions such as Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee (SPCC). SPCC is a local environmental institution that focuses on the waste management in the national park and its buffer zone. Their achievements have been exemplary. They were able to collect 10,000 kg of garbage from the Everest region and bring it to Kathmandu for processing. The World Heritage committee is concerned, and although it appreciates the efforts of the SPCC, it has suggested that the State Party cope with the ever-increasing solid and liquid waste, including the discard from hydropower plants. The State Party has been advised to incorporate adequate management practices in the management plan 2016–2020, including rules for using helicopters for transport and illegal firewood collection. The final verdict on the controversial Kongde View Resort has been given by the Nepali Supreme Court, and the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation (DNPWC) submitted it to the World Heritage Centre on 1 September 2019. As mentioned previously, climate change is one of the most serious challenges for the national park and might affect the Outstanding Universal Value of the site. Glacial hazards such as avalanches, debris flow, glacial fluctuations and glacial surges might be the immediate outcome of climate change in SNP. To overcome this situation, the DNPWC and the staff of the national park worked closely with the UNDP-funded “Community Based Flood and Glacial Lake Outburst Risk Reduction Project” and monitored the activities in the national park and its buffer zone. All the papers and documents of the project have also been given to the local communities. However, the information provided by the papers of the project does not clarify how local communities and their values can be integrated in the project and its management. An updated map of Sagarmatha National Park and its buffer zone has also been created. The park zonation is clearly visible now: the extent of the core zone is 1148 km2, and that of the buffer zone is 275 km2, including the settlements inside the park, as per the declaration in the Nepal Gazette regarding the buffer zone. The DNPWC and the park authority have proposed that the buffer zone of SNP be declared the buffer zone of the World Heritage Property, but the buffer zone management committee, the elected local bodies and local communities are not supporting this proposal. The environmental impact assessment (EIA) report was reviewed by the World Heritage Centre, and the DNPWC has asked Everest Link Pvt. Ltd. (concerned company) to incorporate the comments and recommendations made by the IUCN. The urbanization and development expectations of the people of Nepal and the new political transformations in Nepal are creating a huge problem for conservation, and climate change is not helping much. If development and conservation are not balanced, then there will be dire consequences for SNP and its Outstanding Universal Value.

The evaluation of the 2020 IUCN World Heritage Outlook showed that although the Outstanding Universal Significance of the park remains intact, the tourism, overexploitation of nature, development and pollution are compromising the world heritage value of SNP. In addition, climate change is also a concern for the high mountain ecosystem, the biodiversity and natural processes. A shortage of staff members and funding for the park’s management and maintenance are also affecting the SNP. The IUCN World Heritage Outlook suggests that international attention and scientific research might help address the threats to the World Heritage Site.

The inscription of Sagarmatha National Park in the World Heritage Site List has had an overall positive impact on the conservation of the majestic national park. The inscription has helped in policy making, management, research and other aspects of conserving the national park and its OUV.