Nanda Devi and Valley of Flowers National Parks (335)

Nanda Devi and Valley of Flowers is a mesmerizing natural heritage site that comprises two remarkable components, the Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve and the Valley of flowers National Park. The site is located in the state of Uttarakhand. The Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve features Nanda Devi peak (7817 m) below which is the Rishi Ganga Gorge, the world’s deepest gorge. With rich biodiversity, the site has been known for long as the home of the majestic snow leopard, musk deer and Himalayan snowcock. Endemic trees such as the fir, rhododendron and Himalayan birch are dominant in the Rishi Ganga Gorge. Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve is home to many plant species of medicinal value. In recent years, ecotourism helps in spreading awareness on biodiversity of the site. As per the IUCN World Heritage Outlook, the site ranked as "good with some concern" in 2020.

Nanda Devi and Valley of Flowers is a mesmerizing natural heritage site that comprises two remarkable components, the Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve and the Valley of flowers National Park. The site is located in the state of Uttarakhand. The Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve features Nanda Devi peak (7817 m) below which is the Rishi Ganga Gorge, the world’s deepest gorge. With rich biodiversity, the site has been known for long as the home of the majestic snow leopard, musk deer and Himalayan snowcock. Endemic trees such as the fir, rhododendron and Himalayan birch are dominant in the Rishi Ganga Gorge. Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve is home to many plant species of medicinal value. In recent years, ecotourism helps in spreading awareness on biodiversity of the site. As per the IUCN World Heritage Outlook, the site ranked as "good with some concern" in 2020.

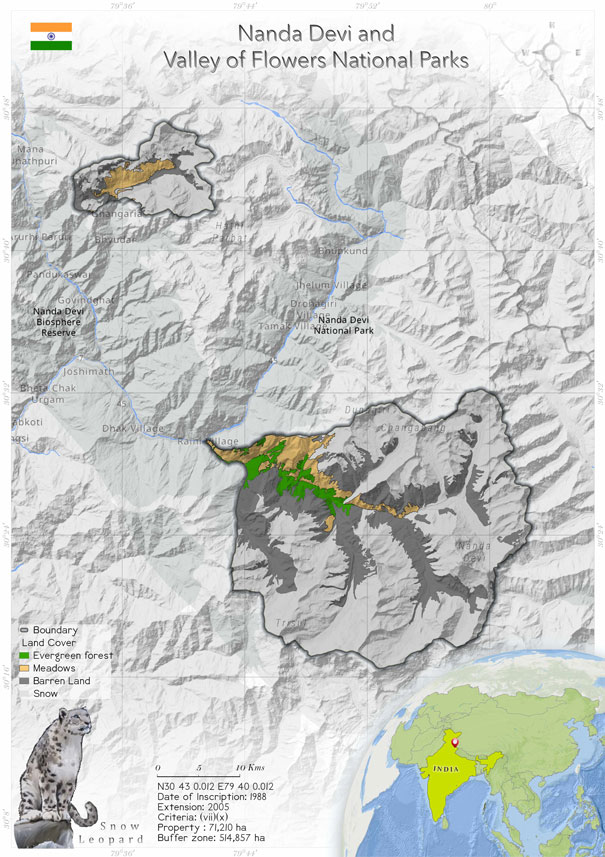

Nanda Devi and Valley of Flowers is an amalgam of Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve and Valley of Flowers National Park, nestled in the Western Himalayan terrain. Declared in 1988, this World Heritage Site has been gaining attention for its exquisite landscapes and unique biodiversity (UNESCOwhc.unesco.org). Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve is located in Chamoli District, of Uttarakhand (Bosak 2008). It has a central core zone of 625 km2 surrounded by a buffer zone of 1612 km2 (Maikhuri et al. 2001). The core zone features Nanda Devi peak (7817 m), which is the second highest peak of India, adjacent the world’s deepest gorge, the Rishi Ganga Gorge (UNESCO whc.unesco.org). The western end of the Rishi Ganga Gorge is at the conjunction of the Rishi Ganga River and the Dhauli Ganga, which further flows into the Alaknanda, in the south. The Dhauli Ganga River then enters the Niti Valley, which extends northward to the Tibetan Plateau via the Niti Pass (Bosak 2008). The entire valley of Rishi Ganga was declared a sanctuary in 1939 (Rao et al. 2003). Glaciers and alpine meadows are mostly seen in the core zone of the reserve (Maikhuri et al. 2001). There are three seasons— summer (April–June), rainy (June–September), and winter (October– March). About 47.8% of the average annual rainfall of 928.81 mm falls over a two months period (July–August), which implies a strong impact of the monsoon. The maximum temperature ranges from 14°C to 24°C and the minimum temperature ranges from 3°C to 7.5°C (Rao et al. 2002).

The biodiversity of the Nanda Devi and Valley of Flowers heritage site is known for its endemism and uniqueness. According to early reports and botanical surveys conducted in Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, there are about 400 species of trees, 552 species of herbs and shrubs and 18 species of grasses (Kacher 1976, 1977, Hajra and Jain 1983, Department of Environment 1987, Balodi, 1993, Samant 1993). The landscape is divided into three ecological zones-mixed temperate and tropical forests at the lower altitudes and Bhoj forests (forests of Betula jacqemontii) in a belt that extends from Lata to Reni and to Dhibrugheta (Bosak 2008). These forests are known for their trailing lichen and understory of dwarf rhododendron (Rhododendron yakushimanum). The Rishi Gorge is dominated by forests of fir (Pinus spectabilis), rhododendron (Rhododendron campanulatum ssp. aeruginosum) and Himalayan birch (Betula jacqemontii) (Samant 1993). The rare, threatened snow leopard (Panthera uncia), brown bear (Ursus arctos isabellinus), musk deer (Moschus chrysogaster), monal pheasant (Lophophorus impejanus), Himalayan snow cock (Tetraogallus himalayensis) and snow partridge Lerwalerwa are some of the endemic animals of the reserve (Maikhuri et al. 2001). In the alpine pastures, the bharal or blue sheep (Pseudois nayaur) are sighted grazing in large herds, while in the forests of the Rishi Gorge and the buffer zone, Himalayan tahr (Hemitragus jemlahicus) are very common (Bosak 2008). Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve is also famous for being the home of many ethnobotanical plants, e.g., Aconitum heterophyllum, Podophyllum hexandrum, Dactylorhiza hatagirea, Nardostachys grandiflora, and Taxus baccata (Maikhuri et al. 2001).

Nanda Devi and Valley of Flowers forms a very significant part of the Indian Himalayan Region (IHR), which is a hotspot of 1748 species of medicinal plant (Samant et al. 1998) and 675 species of wild edible plant (Samant& Dhar 1997). The Valley of Flowers National Park is home to over 520 vascular plant species, of which 498 are flowering plants, four are gymnosperms and 18 are ferns (Kala et al. 2002). A total of 112 species are said to have medicinal uses (Kala 1998). Additionally, 472 herbs, 41 shrubs and eight tree species have been recorded from the national park (Kala 2005).

Nanda Devi and Valley of Flowers is an amalgam of Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve and Valley of Flowers National Park, nestled in the Western Himalayan terrain. Declared in 1988, this World Heritage Site has been gaining attention for its exquisite landscapes and unique biodiversity (UNESCOwhc.unesco.org). Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve is located in Chamoli District, of Uttarakhand (Bosak 2008). It has a central core zone of 625 km2 surrounded by a buffer zone of 1612 km2 (Maikhuri et al. 2001). The core zone features Nanda Devi peak (7817 m), which is the second highest peak of India, adjacent the world’s deepest gorge, the Rishi Ganga Gorge (UNESCO whc.unesco.org). The western end of the Rishi Ganga Gorge is at the conjunction of the Rishi Ganga River and the Dhauli Ganga, which further flows into the Alaknanda, in the south. The Dhauli Ganga River then enters the Niti Valley, which extends northward to the Tibetan Plateau via the Niti Pass (Bosak 2008). The entire valley of Rishi Ganga was declared a sanctuary in 1939 (Rao et al. 2003). Glaciers and alpine meadows are mostly seen in the core zone of the reserve (Maikhuri et al. 2001). There are three seasons— summer (April–June), rainy (June–September), and winter (October– March). About 47.8% of the average annual rainfall of 928.81 mm falls over a two months period (July–August), which implies a strong impact of the monsoon. The maximum temperature ranges from 14°C to 24°C and the minimum temperature ranges from 3°C to 7.5°C (Rao et al. 2002).

The biodiversity of the Nanda Devi and Valley of Flowers heritage site is known for its endemism and uniqueness. According to early reports and botanical surveys conducted in Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, there are about 400 species of trees, 552 species of herbs and shrubs and 18 species of grasses (Kacher 1976, 1977, Hajra and Jain 1983, Department of Environment 1987, Balodi, 1993, Samant 1993). The landscape is divided into three ecological zones-mixed temperate and tropical forests at the lower altitudes and Bhoj forests (forests of Betula jacqemontii) in a belt that extends from Lata to Reni and to Dhibrugheta (Bosak 2008). These forests are known for their trailing lichen and understory of dwarf rhododendron (Rhododendron yakushimanum). The Rishi Gorge is dominated by forests of fir (Pinus spectabilis), rhododendron (Rhododendron campanulatum ssp. aeruginosum) and Himalayan birch (Betula jacqemontii) (Samant 1993). The rare, threatened snow leopard (Panthera uncia), brown bear (Ursus arctos isabellinus), musk deer (Moschus chrysogaster), monal pheasant (Lophophorus impejanus), Himalayan snow cock (Tetraogallus himalayensis) and snow partridge Lerwalerwa are some of the endemic animals of the reserve (Maikhuri et al. 2001). In the alpine pastures, the bharal or blue sheep (Pseudois nayaur) are sighted grazing in large herds, while in the forests of the Rishi Gorge and the buffer zone, Himalayan tahr (Hemitragus jemlahicus) are very common (Bosak 2008). Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve is also famous for being the home of many ethnobotanical plants, e.g., Aconitum heterophyllum, Podophyllum hexandrum, Dactylorhiza hatagirea, Nardostachys grandiflora, and Taxus baccata (Maikhuri et al. 2001).

Nanda Devi and Valley of Flowers forms a very significant part of the Indian Himalayan Region (IHR), which is a hotspot of 1748 species of medicinal plant (Samant et al. 1998) and 675 species of wild edible plant (Samant& Dhar 1997). The Valley of Flowers National Park is home to over 520 vascular plant species, of which 498 are flowering plants, four are gymnosperms and 18 are ferns (Kala et al. 2002). A total of 112 species are said to have medicinal uses (Kala 1998). Additionally, 472 herbs, 41 shrubs and eight tree species have been recorded from the national park (Kala 2005).

Criterion (vii)

The Nanda Devi National Park is renowned for its remote mountain wilderness, dominated by India's second highest mountain at 7,817 m and protected on all sides by spectacular topographical features including glaciers, moraines, and alpine meadows. This spectacular landscape is complemented by the Valley of Flowers, an outstandingly beautiful high-altitude Himalayan valley. Its ‘gentle’ landscape, breath-taking beautiful meadows of alpine flowers and ease of access has been acknowledged by renowned explorers, mountaineers and botanists in literature for over a century and in Hindu mythology for much longer.

The Nanda Devi National Park is renowned for its remote mountain wilderness, dominated by India's second highest mountain at 7,817 m and protected on all sides by spectacular topographical features including glaciers, moraines, and alpine meadows. This spectacular landscape is complemented by the Valley of Flowers, an outstandingly beautiful high-altitude Himalayan valley. Its ‘gentle’ landscape, breath-taking beautiful meadows of alpine flowers and ease of access has been acknowledged by renowned explorers, mountaineers and botanists in literature for over a century and in Hindu mythology for much longer.

Criterion (x)

The Nanda Devi National Park, with its wide range of high-altitude habitats, holds significant populations of flora and fauna including a number of threatened mammals, notably snow leopard and Himalayan musk deer, as well as a large population of bharal, or blue sheep. Abundance estimates for wild ungulates, galliformes and carnivores within the Nanda Devi National Park are higher than those in similar protected areas in the western Himalayas. The Valley of Flowers is internationally important on account of its diverse alpine flora, representative of the West Himalaya biogeographic zone. The rich diversity of species reflects the valley’s location within a transition zone between the Zanskar and Great Himalaya ranges to the north and south, respectively, and between the Eastern and Western Himalaya flora. A number of plant species are globally threatened, several have not been recorded from elsewhere in Uttarakhand and two have not been recorded in Nanda Devi National Park. The diversity of threatened species of medicinal plants is higher than has been recorded in other Indian Himalayan protected areas. The entire Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve lies within the Western Himalayas Endemic Bird Area (EBA). Seven restricted-range bird species are endemic to this part of the EBA.

Status

After its declaration as a World Heritage Site, Nanda Devi and the Valley of Flowers has come under intense scrutiny and inspection. Although the rough terrain and inaccessible mountain altitudes are beneficial for its protection, human-induced disturbances in the buffer zone seem to be impacting the values of the heritage site (IUCN 2020).

An extensive study of the effects of anthropogenic disturbances on the sub-alpine forests of Valley of Flowers National Park found that the buffer zone of the park was subjected to grazing, to logging of trees for fuel wood, timber and fodder and to tourism (Gairola et al. 2009). The national park has three forest types, namely, broadleaved birch (Betula utilis), coniferous fir (Abies pindrow) and mixed broadleaved maple (Acer) forests (Bharti et al. 2011; Gairola et al. 2009; Kala & Uniyal 1999). It was concluded that the tree density of these species significantly reduced with the increase in anthropogenic disturbances (Gairola et al. 2015).

Nanda Devi and the Valley of Flowers has become a centre of attraction for tourists. But the increase in the tourist influx has affected the landscape and the ecological condition of the heritage site. It has been noted that there has been a surge in pilgrimage visits due to the presence of prominent shrines such as Badrinath and Hemkund Sahib in the buffer zone (~1.5 million per year) (Dobriyal et al. 2017; Gupta et al. 2018; Tiwari 2019). The consequences of this escalated tourism are trail erosion, undisposed non-biodegradable rubbish, water pollution due to human waste and sewage and introduction of invasive alien plants, which are highly undesirable in the fragile Himalayan ecosystem (Huddart & Stott 2020). Another issue is that most often the pilgrims and trekkers pluck parts of endemic plants such as Saussurea obvallata (brahmakamal), Aconitum heterophyllum, Arnebia benthamii, Betula utilis, Corydalis spp., Dactylorhiza hatagirea, Orchis habenarioides, Picrorhiza kurroa,Taxus wallichiana, Angelica glauca, Carum carvi, Hyssopus officinalis, Juniperus spp., Jurinea dolomiaea, Nardostachys grandiflora, Origanum vulgare, Pleurospermum brunois, Saussurea costus, Thymus linearia and Valeriana hardwickii, which impacts the population ecology (Maikhuri et al. 2017; Kumar 2017; Negi et al. 2019). Ecotourism helps spread awareness on biodiversity conservation and protecting the values of a heritage site and provides a steady revenue inflow (Kala & Maikhuri 2011). Ecotourism emphasizes the need for planning and sustainable growth of the tourism industry, and it seeks to ensure that tourism development does not exceed the social and environmental carrying capacity (Bornemeier et al. 1997). It may help maintaining the integrity of Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve. The IUCN conservation outlook for Nanda Devi and Valley of Flowers was “Good with some concerns” in 2020.

After its declaration as a World Heritage Site, Nanda Devi and the Valley of Flowers has come under intense scrutiny and inspection. Although the rough terrain and inaccessible mountain altitudes are beneficial for its protection, human-induced disturbances in the buffer zone seem to be impacting the values of the heritage site (IUCN 2020).

An extensive study of the effects of anthropogenic disturbances on the sub-alpine forests of Valley of Flowers National Park found that the buffer zone of the park was subjected to grazing, to logging of trees for fuel wood, timber and fodder and to tourism (Gairola et al. 2009). The national park has three forest types, namely, broadleaved birch (Betula utilis), coniferous fir (Abies pindrow) and mixed broadleaved maple (Acer) forests (Bharti et al. 2011; Gairola et al. 2009; Kala & Uniyal 1999). It was concluded that the tree density of these species significantly reduced with the increase in anthropogenic disturbances (Gairola et al. 2015).

Nanda Devi and the Valley of Flowers has become a centre of attraction for tourists. But the increase in the tourist influx has affected the landscape and the ecological condition of the heritage site. It has been noted that there has been a surge in pilgrimage visits due to the presence of prominent shrines such as Badrinath and Hemkund Sahib in the buffer zone (~1.5 million per year) (Dobriyal et al. 2017; Gupta et al. 2018; Tiwari 2019). The consequences of this escalated tourism are trail erosion, undisposed non-biodegradable rubbish, water pollution due to human waste and sewage and introduction of invasive alien plants, which are highly undesirable in the fragile Himalayan ecosystem (Huddart & Stott 2020). Another issue is that most often the pilgrims and trekkers pluck parts of endemic plants such as Saussurea obvallata (brahmakamal), Aconitum heterophyllum, Arnebia benthamii, Betula utilis, Corydalis spp., Dactylorhiza hatagirea, Orchis habenarioides, Picrorhiza kurroa,Taxus wallichiana, Angelica glauca, Carum carvi, Hyssopus officinalis, Juniperus spp., Jurinea dolomiaea, Nardostachys grandiflora, Origanum vulgare, Pleurospermum brunois, Saussurea costus, Thymus linearia and Valeriana hardwickii, which impacts the population ecology (Maikhuri et al. 2017; Kumar 2017; Negi et al. 2019). Ecotourism helps spread awareness on biodiversity conservation and protecting the values of a heritage site and provides a steady revenue inflow (Kala & Maikhuri 2011). Ecotourism emphasizes the need for planning and sustainable growth of the tourism industry, and it seeks to ensure that tourism development does not exceed the social and environmental carrying capacity (Bornemeier et al. 1997). It may help maintaining the integrity of Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve. The IUCN conservation outlook for Nanda Devi and Valley of Flowers was “Good with some concerns” in 2020.