Manas Wildlife Sanctuary (338)

Manas Wildlife Sanctuary was inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 1985, and seven years later it was added to the Danger List of World Heritage due to political instability and ethnic violence. The property is situated in the north-eastern state of Assam, India and has an extent of 391 km2 . The sanctuary is a part of the core zone of Manas Tiger Reserve (28,370 km2 ) and shares a boundary with Royal Manas National Park, Bhutan, in the north. The site’s scenic beauty derives from shifting river channels cutting the forested hills, alluvial grasslands and evergreen forests. The site is home to many threatened and endangered animals including the Bengal tiger, greater one-horned rhino, swamp deer, hog deer, pygmy hog, hispid hare and Bengal florican. The site is significant among the Indian sub-continent’s protected areas as one of the remaining natural areas in the region where source populations of many threatened species continue to survive. The site was removed from the Danger List in 2011. Management actions have also slowly improved through the sustained efforts of the State Party, with the backing of international and national agencies. The current threats identified for the property are poaching, encroachment, proliferation of invasive species and the impacts of existing and proposed upstream hydroelectric projects in Bhutan. At present, the property benefits from government support at both national and regional levels. The property has six national and international designations (National Park, Tiger Reserve, Biosphere Reserve, World Heritage Site, Elephant Reserve and Important Bird Area), with the legal protection and legislative framework being provided by the provisions of Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 ; Biological Diversity Act, 2002 and Indian Forest Act, 1927/Assam Forest Regulation 1891.

Manas Wildlife Sanctuary was inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 1985, and seven years later it was added to the Danger List of World Heritage due to political instability and ethnic violence. The property is situated in the north-eastern state of Assam, India and has an extent of 391 km2 . The sanctuary is a part of the core zone of Manas Tiger Reserve (28,370 km2 ) and shares a boundary with Royal Manas National Park, Bhutan, in the north. The site’s scenic beauty derives from shifting river channels cutting the forested hills, alluvial grasslands and evergreen forests. The site is home to many threatened and endangered animals including the Bengal tiger, greater one-horned rhino, swamp deer, hog deer, pygmy hog, hispid hare and Bengal florican. The site is significant among the Indian sub-continent’s protected areas as one of the remaining natural areas in the region where source populations of many threatened species continue to survive. The site was removed from the Danger List in 2011. Management actions have also slowly improved through the sustained efforts of the State Party, with the backing of international and national agencies. The current threats identified for the property are poaching, encroachment, proliferation of invasive species and the impacts of existing and proposed upstream hydroelectric projects in Bhutan. At present, the property benefits from government support at both national and regional levels. The property has six national and international designations (National Park, Tiger Reserve, Biosphere Reserve, World Heritage Site, Elephant Reserve and Important Bird Area), with the legal protection and legislative framework being provided by the provisions of Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 ; Biological Diversity Act, 2002 and Indian Forest Act, 1927/Assam Forest Regulation 1891.

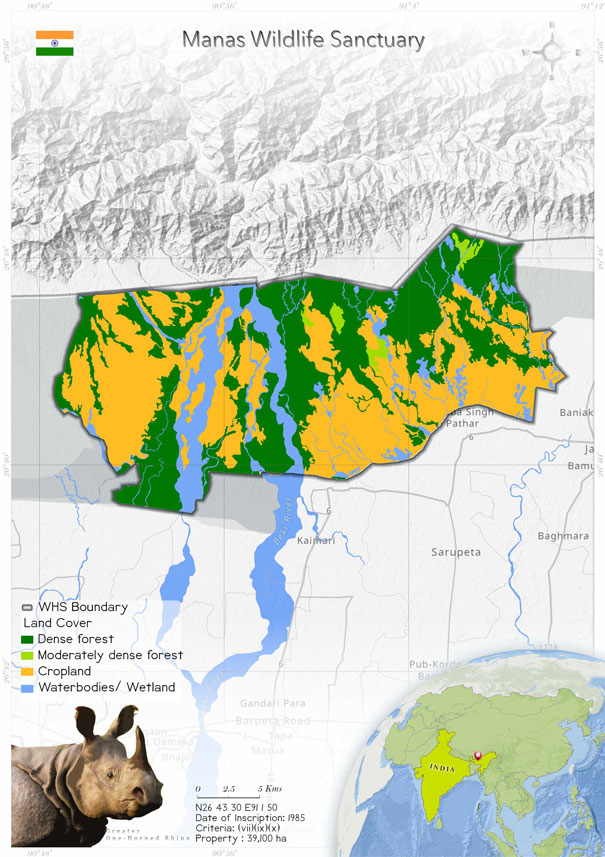

The Manas World Heritage Site (MWHS), located (26° 35' to 26°50' N, 90° 45' 91° 15' E) in Baksa and Chirang districts, of Assam, at the junction of the Indo-Gangetic, Indo-Malayan and Indo-Bhutan realms, is a strategic conservation area in the Jigme Dorji-Manas-Bumdeling Conservation Landscape, in the Eastern Himalayan Eco-region (Wikramanayake et al., 2001). MWHS occupies an area of 391 km2 , which forms the core area of Manas National Park (500 km2 ) and Manas Tiger Reserve (2837 km2 ). MWHS extends on both sides of the Manas River and is restricted to the north by the international border of Bhutan, to the south by densely populated villages and to the east and west by reserve forests. It is situated in the Eastern Duar and has extensive bhabar and terai grassland areas that are typical of the Himalayan foothills. The altitude ranges from 50 m above MSL, on the southern boundary, to 250 m above MSL, along the Bhutan Hills. The humidity levels are high and can reach up to 76%. The mean annual rainfall is 3330 mm. November-February is relatively dry, and the smaller rivers dry up, causing an acute water shortage in the bhabhar areas. The mean temperature ranges from 5°C to 37°C. Floristically, the park (Sarma et al. 2008) consists of woodlands and savannah grasslands. In the woodlands are tree species mostly belonging to the semi-evergreen forest and moist mixed deciduous forest. The area under the semi-evergreen category is 233.31 km2 , and it is distributed mostly in the northern part and the extreme south-west of the park. The savannah grasslands are dominated by tall grasses such as Narenga porphyrocoma, Imperata cylindrica, Phragmites karka, Arundo donax, Saccharum spontaneum, Themeda arundinacea, Saccharum procerum and Vetiveria zizaanioides, These are interspersed with trees such as Bombax ceiba and Dillenia indica. The total area under this category is 161.98 km2 . Alluvial grasslands (44.49 km2 ) are scattered across the park. They are characterized by pure patches of grasslands and presence of water during the rainy season.

Manas is an outstanding case of a rare combination of a Sub-Himalayan Bhabar Terai formation with riverine succession leading up to Sub-Himalayan Mountain Forest. This Indo-Bhutan transboundary protected area is home to around 37 species of threatened mammal and 28 species of threatened bird listed in the IUCN Red List (Ghosh et al, 2014). The grasslands in Manas are important for the conservation of threatened species such as the greater one-horned rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis), tiger (Panthera tigris), swamp deer (Rucervus duvaucelii), hispid hare (Caprolagus hispidus), pygmy hog (Porcula salvinus), hog deer (Axis porcinus), Asiatic wild buffalo (Bubulus arnee), Asian elephant (Elephas maximas) and Bengal florican (Houbaropsis bengalensis).

The Manas World Heritage Site (MWHS), located (26° 35' to 26°50' N, 90° 45' 91° 15' E) in Baksa and Chirang districts, of Assam, at the junction of the Indo-Gangetic, Indo-Malayan and Indo-Bhutan realms, is a strategic conservation area in the Jigme Dorji-Manas-Bumdeling Conservation Landscape, in the Eastern Himalayan Eco-region (Wikramanayake et al., 2001). MWHS occupies an area of 391 km2 , which forms the core area of Manas National Park (500 km2 ) and Manas Tiger Reserve (2837 km2 ). MWHS extends on both sides of the Manas River and is restricted to the north by the international border of Bhutan, to the south by densely populated villages and to the east and west by reserve forests. It is situated in the Eastern Duar and has extensive bhabar and terai grassland areas that are typical of the Himalayan foothills. The altitude ranges from 50 m above MSL, on the southern boundary, to 250 m above MSL, along the Bhutan Hills. The humidity levels are high and can reach up to 76%. The mean annual rainfall is 3330 mm. November-February is relatively dry, and the smaller rivers dry up, causing an acute water shortage in the bhabhar areas. The mean temperature ranges from 5°C to 37°C. Floristically, the park (Sarma et al. 2008) consists of woodlands and savannah grasslands. In the woodlands are tree species mostly belonging to the semi-evergreen forest and moist mixed deciduous forest. The area under the semi-evergreen category is 233.31 km2 , and it is distributed mostly in the northern part and the extreme south-west of the park. The savannah grasslands are dominated by tall grasses such as Narenga porphyrocoma, Imperata cylindrica, Phragmites karka, Arundo donax, Saccharum spontaneum, Themeda arundinacea, Saccharum procerum and Vetiveria zizaanioides, These are interspersed with trees such as Bombax ceiba and Dillenia indica. The total area under this category is 161.98 km2 . Alluvial grasslands (44.49 km2 ) are scattered across the park. They are characterized by pure patches of grasslands and presence of water during the rainy season.

Manas is an outstanding case of a rare combination of a Sub-Himalayan Bhabar Terai formation with riverine succession leading up to Sub-Himalayan Mountain Forest. This Indo-Bhutan transboundary protected area is home to around 37 species of threatened mammal and 28 species of threatened bird listed in the IUCN Red List (Ghosh et al, 2014). The grasslands in Manas are important for the conservation of threatened species such as the greater one-horned rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis), tiger (Panthera tigris), swamp deer (Rucervus duvaucelii), hispid hare (Caprolagus hispidus), pygmy hog (Porcula salvinus), hog deer (Axis porcinus), Asiatic wild buffalo (Bubulus arnee), Asian elephant (Elephas maximas) and Bengal florican (Houbaropsis bengalensis).

Criterion (vii)

Manas is recognized not only for its rich biodiversity but also for its spectacular scenery and natural landscape. Manas is located at the foothills of the Eastern Himalayas. The northern boundary of the park is contiguous to the international border of Bhutan manifested by the imposing Bhutan hills. It spans on either side of the majestic Manas river flanked in the east and the west by reserved forests. The tumultuous river swirling down the rugged mountains in the backdrop of forested hills coupled with the serenity of the alluvial grasslands and tropical evergreen forests offers a unique wilderness experience.

Manas is recognized not only for its rich biodiversity but also for its spectacular scenery and natural landscape. Manas is located at the foothills of the Eastern Himalayas. The northern boundary of the park is contiguous to the international border of Bhutan manifested by the imposing Bhutan hills. It spans on either side of the majestic Manas river flanked in the east and the west by reserved forests. The tumultuous river swirling down the rugged mountains in the backdrop of forested hills coupled with the serenity of the alluvial grasslands and tropical evergreen forests offers a unique wilderness experience.

Criterion (ix)

The Manas-Beki system is the major river system flowing through the property and joining the Brahmaputra river further downstream. These and other rivers carry an enormous amount of silt and rock debris from the foothills resulting from the heavy rainfall, fragile nature of the rock and steep gradients of the catchments. This leads to the formation of alluvial terraces, comprising deep layers of deposited rock and detritus overlain by sandy loam and a layer of humus represented by bhabar tracts in the north. The terai tract in the south consists of fine alluvial deposits with underlying pans where the water table lies near to the surface. The area contained by the Manas-Beki system gets inundated during the monsoons but flooding does not last long due to the sloping relief. The monsoon and river system form four principal geological habitats: Bhabar savannah, Terai tract, marshlands and riverine tracts. The dynamic ecosystem processes support broadly three types of vegetation: semi-evergreen forests, mixed moist and dry deciduous forests and alluvial grasslands. The dry deciduous forests represent an early stage in succession that is constantly renewed by floods and is replaced by moist deciduous forests away from water courses, which in turn are replaced by semi evergreen climax forests. The vegetation of Manas has tremendous regenerating and self-sustaining capabilities due to its high fertility and response to natural grazing by herbivorous animals.

Criterion (x)

The Manas Wildlife Sanctuary provides habitat for 22 of India’s most threatened species of mammals. In total, there are nearly 60 mammal species, 42 reptile species, 7 amphibians and 500 species of birds, of which 26 are globally threatened. Noteworthy among these are the elephant, tiger, greater one-horned rhino, clouded leopard, sloth bear, and other species. The wild buffalo population is probably the only pure strain of this species still found in India. It also harbours endangered species like pygmy hog, hispid hare, golden langur and Bengal florican. The range of habitats and vegetation also accounts for high plant diversity that includes 89 tree species, 49 shrubs, 37 undershrubs, 172 herbs and 36 climbers. Fifteen species of orchids, 18 species of fern and 43 species of grasses that provide vital forage to a range of ungulate species also occur here.

Status

The site was listed as in danger between 1992 and 2011 by the World Heritage Committee, due to ethnic violations. During this time (from 1988 to 1993), the infrastructure of the heritage site suffered massive damage and political instability demolished nearly all the park’s one-horn rhinoceroses and 50% of its tigers, apart from reducing the populations of the swamp deer (Das et al. 2009; Borah et al. 2013), pygmy hog and Bengal florican (Lahkar et al. 2018). Subsequently, grassland species declined drastically because of selective hunting by both opportunistic hunters and the anti-government forces (Goswami & Ganesh 2014). Sinha et al. (2019) found that the possible drivers of the hog deer decline in Manas were habitat degradation and hunting. The grasslands that the hog deer prefers has been reduced in area over the last four decades (Sarma et al. 2008, Sinha et al. 2019). The grassland patches, particularly near the southern boundary of the park, mostly in the central range, which were prime hog deer habitats (Sinha et al. 2019), are heavily infested with invasive plants such as Chromolaena odorata and Mikania micrantha (Nath et al. 2019).

Political stability was attained with the formation of the Bodoland Territorial Council in 2003, and subsequently the conservation intervention gained momentum, including restocking of the rhino population. There were occasional conflicts in the Western Range (Panbari) until 2016 (Lahkar et al. 2018). However, the grazing pressure from domestic cattle is still an issue that needs to be addressed by the site manager. Approximately 2000 cattle graze inside the park each day during the dry season (Sinha et al. 2019). A recent study shows that the ethno-political conflict has also influenced the spatial distribution of several species of mammal (Lahkar et al. 2019). Apart from this, the potential impacts arising from hydro-electric development in the neighbouring Bhutan are predicted to have both direct and indirect impact on the OUVs of the property.

Continuous monitoring and provision of support to the site can reduce the threats and improve the conservation efforts of the property. The recent SoC report mentions that factors such as civil unrest, wildlife poaching, timber logging, illegal cultivation, slow release of funds, uncontrolled infrastructure development by local tourism groups, invasive and alien species, military training at the site and development of water infrastructure are affecting the property. Thanks to intensified anti-poaching efforts, there were no reports of rhino poaching on the property since April 2016. However, one tiger was killed outside the property in July 2017. The poachers were arrested, and the animal’s body parts were confiscated. The establishment of Eco-Development Committees (EDCs), which provide livelihood support to local villagers, and intensification of patrolling have helped prevent poaching. The proliferation of invasive plant species, such as Chromolaena odorata and Mikania micrantha, is of utmost concern. Trans-boundary cooperation has also been intensified, and funding for the property had been increased and diversified. However, the State Party of Bhutan has also not provided any information on the status of the proposed Mangdechhu hydro-electric project to the WH Committee yet. This hydropower project could severely affect the OUV of the property.

The evaluation by IUCN World Heritage Outlook (worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org) of heritage sites reveals that the rhino numbers are increasing after 19 years spent by Manas on the List of World Heritage in Danger. The status of other species depends on recovery action, and whilst the site remains fragile and population trend data are limited, it appears that populations are generally recovering. Management actions have also been slowly improved through the sustained efforts of the State Party, with significant international support. Nevertheless, there remain threats such as those from recurring insurgencies, poaching and encroachment. Continued management efforts will be required to avoid a return to the situation of insurgence and insecurity that prevailed in the early 1990s and led to the site’s inclusion on the List of World Heritage in Danger. The World Heritage inscription has had a major positive impact on conservation, recognition, management effectiveness, research and monitoring, institutional coordination, international cooperation, and legal and policy frameworks for protecting the Natural World Heritage Sites.

The site was listed as in danger between 1992 and 2011 by the World Heritage Committee, due to ethnic violations. During this time (from 1988 to 1993), the infrastructure of the heritage site suffered massive damage and political instability demolished nearly all the park’s one-horn rhinoceroses and 50% of its tigers, apart from reducing the populations of the swamp deer (Das et al. 2009; Borah et al. 2013), pygmy hog and Bengal florican (Lahkar et al. 2018). Subsequently, grassland species declined drastically because of selective hunting by both opportunistic hunters and the anti-government forces (Goswami & Ganesh 2014). Sinha et al. (2019) found that the possible drivers of the hog deer decline in Manas were habitat degradation and hunting. The grasslands that the hog deer prefers has been reduced in area over the last four decades (Sarma et al. 2008, Sinha et al. 2019). The grassland patches, particularly near the southern boundary of the park, mostly in the central range, which were prime hog deer habitats (Sinha et al. 2019), are heavily infested with invasive plants such as Chromolaena odorata and Mikania micrantha (Nath et al. 2019).

Political stability was attained with the formation of the Bodoland Territorial Council in 2003, and subsequently the conservation intervention gained momentum, including restocking of the rhino population. There were occasional conflicts in the Western Range (Panbari) until 2016 (Lahkar et al. 2018). However, the grazing pressure from domestic cattle is still an issue that needs to be addressed by the site manager. Approximately 2000 cattle graze inside the park each day during the dry season (Sinha et al. 2019). A recent study shows that the ethno-political conflict has also influenced the spatial distribution of several species of mammal (Lahkar et al. 2019). Apart from this, the potential impacts arising from hydro-electric development in the neighbouring Bhutan are predicted to have both direct and indirect impact on the OUVs of the property.

Continuous monitoring and provision of support to the site can reduce the threats and improve the conservation efforts of the property. The recent SoC report mentions that factors such as civil unrest, wildlife poaching, timber logging, illegal cultivation, slow release of funds, uncontrolled infrastructure development by local tourism groups, invasive and alien species, military training at the site and development of water infrastructure are affecting the property. Thanks to intensified anti-poaching efforts, there were no reports of rhino poaching on the property since April 2016. However, one tiger was killed outside the property in July 2017. The poachers were arrested, and the animal’s body parts were confiscated. The establishment of Eco-Development Committees (EDCs), which provide livelihood support to local villagers, and intensification of patrolling have helped prevent poaching. The proliferation of invasive plant species, such as Chromolaena odorata and Mikania micrantha, is of utmost concern. Trans-boundary cooperation has also been intensified, and funding for the property had been increased and diversified. However, the State Party of Bhutan has also not provided any information on the status of the proposed Mangdechhu hydro-electric project to the WH Committee yet. This hydropower project could severely affect the OUV of the property.

The evaluation by IUCN World Heritage Outlook (worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org) of heritage sites reveals that the rhino numbers are increasing after 19 years spent by Manas on the List of World Heritage in Danger. The status of other species depends on recovery action, and whilst the site remains fragile and population trend data are limited, it appears that populations are generally recovering. Management actions have also been slowly improved through the sustained efforts of the State Party, with significant international support. Nevertheless, there remain threats such as those from recurring insurgencies, poaching and encroachment. Continued management efforts will be required to avoid a return to the situation of insurgence and insecurity that prevailed in the early 1990s and led to the site’s inclusion on the List of World Heritage in Danger. The World Heritage inscription has had a major positive impact on conservation, recognition, management effectiveness, research and monitoring, institutional coordination, international cooperation, and legal and policy frameworks for protecting the Natural World Heritage Sites.