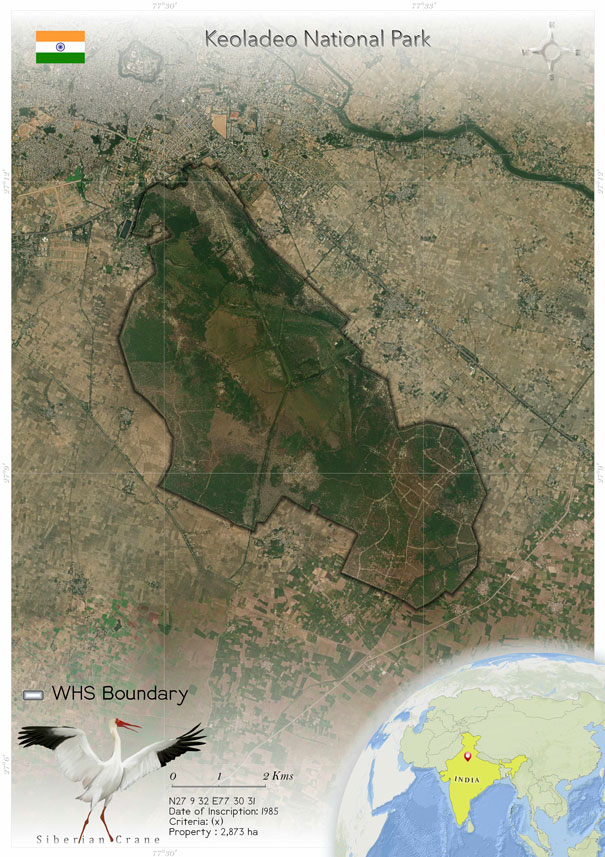

Keoladeo National Park (340)

The Keoladeo National Park is situated in Bharatpur District in the state of Rajasthan in India. It is a man-made wetland and is also included in the Ramsar list of wetlands (Ramsar Sites Information 1981). The site is known as a birder's paradise as it provides a wintering area for many globally threatened species like the greater spotted eagle and imperial eagle. The site has a large gathering of migratory as well as residential birds.

The area was once known as a hunting ground for ducks. In 1981, Keoladeo was designated as a national park, after which hunting became prohibited. The area has a vast diversity of flora and fauna. More than 375 angiosperm species and around 90 wetland species are present here. The faunal species in the park include 350 species of birds, 58 species of fishes, 71 species of butterflies, more than 30 species of dragonflies. A wide variety of forest ecosystems are present, comprising woodlands, scrublands, grasslands, low grasslands, savanna woodlands, with scattered trees and scrubs, plantations and wetlands.

The park is protected under the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, and the Indian Forest Act, 1927, and it is managed by the Rajasthan Forest Department. Water crisis and invasive species like Prosopis, Eichhornia and Paspalum are serious threats to the property. According to the State of Conservation Report, the state party is addressing issues like water supply shortage and effectively controlling the expansion of invasive species.

The Keoladeo National Park is situated in Bharatpur District in the state of Rajasthan in India. It is a man-made wetland and is also included in the Ramsar list of wetlands (Ramsar Sites Information 1981). The site is known as a birder's paradise as it provides a wintering area for many globally threatened species like the greater spotted eagle and imperial eagle. The site has a large gathering of migratory as well as residential birds.

The area was once known as a hunting ground for ducks. In 1981, Keoladeo was designated as a national park, after which hunting became prohibited. The area has a vast diversity of flora and fauna. More than 375 angiosperm species and around 90 wetland species are present here. The faunal species in the park include 350 species of birds, 58 species of fishes, 71 species of butterflies, more than 30 species of dragonflies. A wide variety of forest ecosystems are present, comprising woodlands, scrublands, grasslands, low grasslands, savanna woodlands, with scattered trees and scrubs, plantations and wetlands.

The park is protected under the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, and the Indian Forest Act, 1927, and it is managed by the Rajasthan Forest Department. Water crisis and invasive species like Prosopis, Eichhornia and Paspalum are serious threats to the property. According to the State of Conservation Report, the state party is addressing issues like water supply shortage and effectively controlling the expansion of invasive species.

Keoladeo National Park is a man-made wetland. It is a World Heritage Site and listed by the Ramsar Sites Information Service (Ramsar Sites Information 1981 Convention). It is famous for its avian biodiversity (Choudhary et al. 2021). The park is situated on the Central Asian Flyway of the Asia Pacific Global Migratory Flyway. Thus, the place hosts many migratory waterfowls like ducks, geese, coots, pelicans and waders that come there in winters (Mathur et al. 2009; whc.unesco.org). It is located at the confluence of the Gambhir and Banganga rivers, and it is at a distance of 29 km2 from Bharatpur District of Rajasthan State (Bhadouria et al. 2012).

The site is also a wintering area for globally threatened species like the greater spotted eagle and the imperial eagle. When the breeding season comes, the region has the largest gathering of birds, including 15 species of herons, spoonbills, storks, cormorants and ibis, and in a well-flooded year, over 20,000 birds make their nests (whc.unesco.org). The site is known as a ‘birder's paradise’, home to more than 375 bird species, and the endangered Siberian crane (Grus leucogeranus) sojourns in this specific site in winters (Mathur et al. 2009; whc.unesco.org). The park is known for its wintering grounds of Palaearctic migratory waterfowl and has a large gathering of residential birds.

The wetlands area is the most critical site as it is the primary breeding ground for birds like the sarus crane (Grus antigone), painted stork (Mycteria leucocephala), Asian openbill (Anastomus oscitans), darter (Anhinga melanogaster), and various egrets, herons, ibis and other storks (Mathur et al. 2009).

The park is dependent on a regular water supply from the reservoir that is outside the park. It has dykes and sluices that store water at different depths according to the avifaunal species (whc.unesco.org). It is covered with boundary walls, and some villages and agricultural farms are located in its vicinity (Kalra et al. 2007).

The park has a unique history as the Maharaja of Bharatpur owned the land of Keoladeo, and it was known as his hunting grounds in the year 1850. In 1956, the area was declared a bird sanctuary, but the Maharaja of Bharatpur still had the right to hunting in the area. In 1967, the park was designated as a reserved forest under the Rajasthan Forest Act 1953. In 1981, it was declared a national park and included under the Ramsar Sites Information 1981 List of Wetlands, and in 1985, it was designated as a World Heritage Site under UNESCO (Choudhary et al. 2021). Keoladeo National Park is home to more than 375 angiosperm species, of which 90 are wetland species. The faunal diversity consists of 375 species of birds, including 42 species of raptors and nine species of owls. The park has 58 species of fishes, 71 species of butterflies and more than 30 species of dragonflies (Mathur et al. 2009).

The forest diversity in this area is varied, consisting of woodlands, scrublands, grasslands, low grasslands, savanna woodlands, with scattered trees and scrubs, plantations and wetlands (Mathur et al. 2009). Wetlands cover 10 km2 area of the park (Reddy et al. 2010). The forest in the wetlands is of the dry deciduous type mixed with dry grasslands. The vegetation in the park is predominated by Vachellia nilotica (Babul), Neolamarckia cadamba (Kadam), Syzygium cuminii (Jamun) (Mathur et al. 2009), Azadiracta indica (Neem), Dalbergia sissoo (Shisham), Ficus religiosa (Peepal), Capparis decidua (Ker) and Ziziphus mauritiana (Ber) (Reddy et al. 2010; Kalra et al. 2007).

In the Koladhar area, the major grass species in the savanna type of vegetation are Vetiveria zizanioides and Desmostachya bipinnata. These species support many herbivores such as chital, sambar, nilgai, feral animals and domestic cattle. The tree and shrub species in the savanna are Prosopis cineraria, Acacia nilotica, A. leucophloea, Ziziphus mauritiana and Salvadora persica. The wetland area is occupied by low grasslands, primarily by Sporobolus helvolus and Cynodon dactylon. Some species such as Acacia nilotica, Prosopis cineraria, Salvadora persica and Krignelia reticulate are found scattered (Mathur et al. 2009).

The number of faunal species is also increasing in the park. An increasing trend in the densities of three major herbivore species, the wild boar, spotted deer, and blue bull, has been seen for the last 25 years (Singh et al. 2017). Twenty-two species of burrowing animals are also seen in the park, consisting of 10 mammals, eight birds, three reptiles and one amphibian. The Indian rock python (Python molurus) has been sighted in great numbers (Mukherjee et al. 2019).

Keoladeo National Park is a man-made wetland. It is a World Heritage Site and listed by the Ramsar Sites Information Service (Ramsar Sites Information 1981 Convention). It is famous for its avian biodiversity (Choudhary et al. 2021). The park is situated on the Central Asian Flyway of the Asia Pacific Global Migratory Flyway. Thus, the place hosts many migratory waterfowls like ducks, geese, coots, pelicans and waders that come there in winters (Mathur et al. 2009; whc.unesco.org). It is located at the confluence of the Gambhir and Banganga rivers, and it is at a distance of 29 km2 from Bharatpur District of Rajasthan State (Bhadouria et al. 2012).

The site is also a wintering area for globally threatened species like the greater spotted eagle and the imperial eagle. When the breeding season comes, the region has the largest gathering of birds, including 15 species of herons, spoonbills, storks, cormorants and ibis, and in a well-flooded year, over 20,000 birds make their nests (whc.unesco.org). The site is known as a ‘birder's paradise’, home to more than 375 bird species, and the endangered Siberian crane (Grus leucogeranus) sojourns in this specific site in winters (Mathur et al. 2009; whc.unesco.org). The park is known for its wintering grounds of Palaearctic migratory waterfowl and has a large gathering of residential birds.

The wetlands area is the most critical site as it is the primary breeding ground for birds like the sarus crane (Grus antigone), painted stork (Mycteria leucocephala), Asian openbill (Anastomus oscitans), darter (Anhinga melanogaster), and various egrets, herons, ibis and other storks (Mathur et al. 2009).

The park is dependent on a regular water supply from the reservoir that is outside the park. It has dykes and sluices that store water at different depths according to the avifaunal species (whc.unesco.org). It is covered with boundary walls, and some villages and agricultural farms are located in its vicinity (Kalra et al. 2007).

The park has a unique history as the Maharaja of Bharatpur owned the land of Keoladeo, and it was known as his hunting grounds in the year 1850. In 1956, the area was declared a bird sanctuary, but the Maharaja of Bharatpur still had the right to hunting in the area. In 1967, the park was designated as a reserved forest under the Rajasthan Forest Act 1953. In 1981, it was declared a national park and included under the Ramsar Sites Information 1981 List of Wetlands, and in 1985, it was designated as a World Heritage Site under UNESCO (Choudhary et al. 2021). Keoladeo National Park is home to more than 375 angiosperm species, of which 90 are wetland species. The faunal diversity consists of 375 species of birds, including 42 species of raptors and nine species of owls. The park has 58 species of fishes, 71 species of butterflies and more than 30 species of dragonflies (Mathur et al. 2009).

The forest diversity in this area is varied, consisting of woodlands, scrublands, grasslands, low grasslands, savanna woodlands, with scattered trees and scrubs, plantations and wetlands (Mathur et al. 2009). Wetlands cover 10 km2 area of the park (Reddy et al. 2010). The forest in the wetlands is of the dry deciduous type mixed with dry grasslands. The vegetation in the park is predominated by Vachellia nilotica (Babul), Neolamarckia cadamba (Kadam), Syzygium cuminii (Jamun) (Mathur et al. 2009), Azadiracta indica (Neem), Dalbergia sissoo (Shisham), Ficus religiosa (Peepal), Capparis decidua (Ker) and Ziziphus mauritiana (Ber) (Reddy et al. 2010; Kalra et al. 2007).

In the Koladhar area, the major grass species in the savanna type of vegetation are Vetiveria zizanioides and Desmostachya bipinnata. These species support many herbivores such as chital, sambar, nilgai, feral animals and domestic cattle. The tree and shrub species in the savanna are Prosopis cineraria, Acacia nilotica, A. leucophloea, Ziziphus mauritiana and Salvadora persica. The wetland area is occupied by low grasslands, primarily by Sporobolus helvolus and Cynodon dactylon. Some species such as Acacia nilotica, Prosopis cineraria, Salvadora persica and Krignelia reticulate are found scattered (Mathur et al. 2009).

The number of faunal species is also increasing in the park. An increasing trend in the densities of three major herbivore species, the wild boar, spotted deer, and blue bull, has been seen for the last 25 years (Singh et al. 2017). Twenty-two species of burrowing animals are also seen in the park, consisting of 10 mammals, eight birds, three reptiles and one amphibian. The Indian rock python (Python molurus) has been sighted in great numbers (Mukherjee et al. 2019).

Criterion (x)

The Keoladeo National Park is a wetland of international importance for migratory waterfowl, where birds migrating down the Central Asian flyway congregate before dispersing to other regions. At time of inscription it was the wintering ground for the Critically Endangered Siberian Crane, and is habitat for large numbers of resident nesting birds. Some 375 bird species have been recorded from the property including five Critically Endangered, two Endangered and six vulnerable species. Around 115 species of birds breed in the park which includes 15 water bird species forming one of the most spectacular heronries of the region. The habitat mosaic of the property supports a large number of species in a small area, with 42 species of raptors recorded

The Keoladeo National Park is a wetland of international importance for migratory waterfowl, where birds migrating down the Central Asian flyway congregate before dispersing to other regions. At time of inscription it was the wintering ground for the Critically Endangered Siberian Crane, and is habitat for large numbers of resident nesting birds. Some 375 bird species have been recorded from the property including five Critically Endangered, two Endangered and six vulnerable species. Around 115 species of birds breed in the park which includes 15 water bird species forming one of the most spectacular heronries of the region. The habitat mosaic of the property supports a large number of species in a small area, with 42 species of raptors recorded

Status

The property is protected under the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, and Indian Forest Act, 1927. With the support of national and international conservation organizations and local communities, the park is primarily protected by the Rajasthan Forest Department.

The main threats to the property are the shortage of water supply and invasive species (Mukherjee et al. 2017; whc.unesco.org). Both water quality and quantity are affected. Invasive species like Prosopis, Eichhornia and Paspalum are also causing damage to the property (whc. unesco.org). P. juliflora was planted in some regions of the park to control soil erosion, uphold the sand dunes, and afford fuel wood, feed and food. But it became invasive and started spreading endlessly and causing harm to the native species (Mukherjee et al. 2017). Uncontrolled expansion of the invasive grass species Paspalum distichum drains the oxygen level of the water bodies, which consequently affects the biomass and the bird population (Patra et al. 2017).

Shukla and Dubey, 1996, reported about the excessive growth of wild grass like Paspalum distichum which was subsequently controlled by managing the number of buffaloes allowed inside the park for grazing. The park is surrounded by a 2-m high boundary wall which acts as a barrier to halt poaching, pollution etc. Encroachment or habitations are completely prohibited inside the park. There are strict legal environmental regulations in India, and for any developmental activities inside the park, one has to take approval through the environmental assessment process (whc.unesco.org).

To deal with the water crisis, in 2016 the state party provided 629.81 million cubic feet (mcft) of water to the property, which was released from the Pachna Dam, the Chambal Pipeline Project and the Govardhan Drain. In 2015 a water bird survey was conducted, in which 72 species and 14,780 individuals were identified (State of Conservation Report 2016). A survey of water birds was conducted in January-February 2017 by the site management, the Rajasthan Department, researchers and non-governmental actors. The survey used the Asian Water Bird Census framework, and focused on the nesting population and heronries in the property and its neighbouring satellite wetlands (State of Conservation Report 2018).

The management is working towards the removal of invasive species like Prosopis juliflora, Eichhornia crassipes and the African sharptooth catfish (Clarias gariepinus) with the help of forestry staff, local rickshaw pullers and non-governmental organizations (State of Conservation Report 2018). During May and July 2015, more than 40,000 invasive African sharptooth catfish (Clarias gariepinus) were removed from the property (State of Conservation Report 2016). The management plan (2010-2014) was extended till 30 September 2017 by the State Government of Rajasthan, and the revised management plan will be available soon to the World Heritage Committee (State of Conservation Report 2018). Choudhary et al. (2021) in their study concluded that increase in the land use-land cover and the wild spread of P. juliflora are affecting the habitat quality. The alteration in the habitat quality is causing a decrease in the number of birds. The park's authority has to make better management strategies and action plans to cope with this challenge of habitat degradation (Choudhary et al. 2021).

The property is protected under the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, and Indian Forest Act, 1927. With the support of national and international conservation organizations and local communities, the park is primarily protected by the Rajasthan Forest Department.

The main threats to the property are the shortage of water supply and invasive species (Mukherjee et al. 2017; whc.unesco.org). Both water quality and quantity are affected. Invasive species like Prosopis, Eichhornia and Paspalum are also causing damage to the property (whc. unesco.org). P. juliflora was planted in some regions of the park to control soil erosion, uphold the sand dunes, and afford fuel wood, feed and food. But it became invasive and started spreading endlessly and causing harm to the native species (Mukherjee et al. 2017). Uncontrolled expansion of the invasive grass species Paspalum distichum drains the oxygen level of the water bodies, which consequently affects the biomass and the bird population (Patra et al. 2017).

Shukla and Dubey, 1996, reported about the excessive growth of wild grass like Paspalum distichum which was subsequently controlled by managing the number of buffaloes allowed inside the park for grazing. The park is surrounded by a 2-m high boundary wall which acts as a barrier to halt poaching, pollution etc. Encroachment or habitations are completely prohibited inside the park. There are strict legal environmental regulations in India, and for any developmental activities inside the park, one has to take approval through the environmental assessment process (whc.unesco.org).

To deal with the water crisis, in 2016 the state party provided 629.81 million cubic feet (mcft) of water to the property, which was released from the Pachna Dam, the Chambal Pipeline Project and the Govardhan Drain. In 2015 a water bird survey was conducted, in which 72 species and 14,780 individuals were identified (State of Conservation Report 2016). A survey of water birds was conducted in January-February 2017 by the site management, the Rajasthan Department, researchers and non-governmental actors. The survey used the Asian Water Bird Census framework, and focused on the nesting population and heronries in the property and its neighbouring satellite wetlands (State of Conservation Report 2018).

The management is working towards the removal of invasive species like Prosopis juliflora, Eichhornia crassipes and the African sharptooth catfish (Clarias gariepinus) with the help of forestry staff, local rickshaw pullers and non-governmental organizations (State of Conservation Report 2018). During May and July 2015, more than 40,000 invasive African sharptooth catfish (Clarias gariepinus) were removed from the property (State of Conservation Report 2016). The management plan (2010-2014) was extended till 30 September 2017 by the State Government of Rajasthan, and the revised management plan will be available soon to the World Heritage Committee (State of Conservation Report 2018). Choudhary et al. (2021) in their study concluded that increase in the land use-land cover and the wild spread of P. juliflora are affecting the habitat quality. The alteration in the habitat quality is causing a decrease in the number of birds. The park's authority has to make better management strategies and action plans to cope with this challenge of habitat degradation (Choudhary et al. 2021).