Kaziranga National Park (337)

kaziranga National Park was originally designated a forest reserve in 1905. Later, in 1985, the 430 km2 reserve was designated a Natural World Heritage Site. The distinct landscape and unique habitats, such as floodplains, wetlands and grasslands, are a few of the features that make Kaziranga National Park special. The unique aspect of Kaziranga National Park is that it is home to the largest population of the one-horned rhinoceros in the world. In fact, in 1908, Kaziranga National Park became the first protected area to be declared a rhino conservation region. Other mammals such as the Asian water buffalo, Bengal tiger, leopard and swamp deer are a few species of the vibrant biodiversity of the heritage site. The mighty Brahmaputra, on the northern boundary, and the Karbi Anglong Hills, on the southern boundary, create a profound landscape with river basins, beels and highlands that support a vast range of plant and animal species. Nevertheless, over the years, Kaziranga National Park has faced extreme threats. The primary threat is reckless poaching of the one-horned rhinos. Poaching on an immense scale in the last few decades has put the animal on the endangered list. This has has led to the state government taking stringent steps to protect the last of the standing individuals. Currently, the IUCN has updated the status of the rhino to ‘Vulnerable’ thanks to an increase in numbers. There have been human–wildlife conflicts at the edge for a long time. With continuous land encroachment and intense agriculture in the buffer zone, wild animals tend to raid the crop fields and cause infrastructure destruction. Floods in the heritage site is another factor affecting the property.

kaziranga National Park was originally designated a forest reserve in 1905. Later, in 1985, the 430 km2 reserve was designated a Natural World Heritage Site. The distinct landscape and unique habitats, such as floodplains, wetlands and grasslands, are a few of the features that make Kaziranga National Park special. The unique aspect of Kaziranga National Park is that it is home to the largest population of the one-horned rhinoceros in the world. In fact, in 1908, Kaziranga National Park became the first protected area to be declared a rhino conservation region. Other mammals such as the Asian water buffalo, Bengal tiger, leopard and swamp deer are a few species of the vibrant biodiversity of the heritage site. The mighty Brahmaputra, on the northern boundary, and the Karbi Anglong Hills, on the southern boundary, create a profound landscape with river basins, beels and highlands that support a vast range of plant and animal species. Nevertheless, over the years, Kaziranga National Park has faced extreme threats. The primary threat is reckless poaching of the one-horned rhinos. Poaching on an immense scale in the last few decades has put the animal on the endangered list. This has has led to the state government taking stringent steps to protect the last of the standing individuals. Currently, the IUCN has updated the status of the rhino to ‘Vulnerable’ thanks to an increase in numbers. There have been human–wildlife conflicts at the edge for a long time. With continuous land encroachment and intense agriculture in the buffer zone, wild animals tend to raid the crop fields and cause infrastructure destruction. Floods in the heritage site is another factor affecting the property.

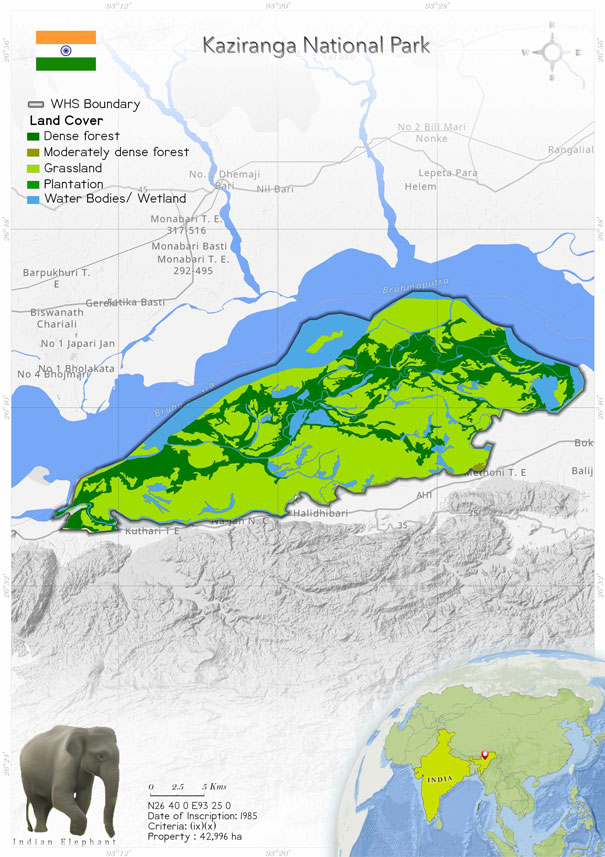

Recognized as a forest reserve in 1905, Kaziranga National Park was inscribed as a Natural World Heritage Site in 1985 (Mathur et al. 2005). It is located in Golaghat, Nagaon and Karbi-Anglong districts, of Assam (between longitudes 92° 50' E and 93° 41' E and latitudes 26° 30' N and 26° 50' N) (Roy 2020). It has an extent of 430 km2 (Barua & Sharma 1999). The park experiences three distinct seasons: summer, monsoon and winter. The summer is generally dry and windy and lasts from mid- February to May, with high temperatures of 37°C being reached. The monsoon (May–September) is warm and humid. The annual rainfall of 2220 mm is received mostly during the monsoon. In winter (November to mid-February), the temperature can go as low as 5°C, with the mean maximum temperature being 25°C. The climate remains dry throughout the season (Roy 2020). The eastern and western areas of the park are at different altitudes (40-80 m) (Roy 2020).

Kaziranga National Park is known for its unique habitats and remarkable biodiversity. The western region of the park is dominated by grasslands, with tall grasses, known as elephant grass, on the higher lands, and short grasses on the lower lands. These grasslands are also found on the the sandy riverine tract of the Brahmaputra and support a rich biodiversity (Chakrabarty et al. 2019). The vegetation is broadly classified into four primary categories: (1) eastern wet alluvial grassland; (2) eastern Dillenia swamp forest; (3) riparian fringing forest; and (4) Assam alluvial plains semi-evergreen forest (Champion & Seth 1968). A wide variety of evergreen and deciduous trees, including Aphanamixis polystachya, Talauma hodgsonii, Dillenia indica, Garcinia tinctoria, Ficus rumphii, Cinnamomum bejolghota, Albizia procera, Duabanga grandiflora, Lagerstroemia speciosa, Crateva unilocularis, Sterculia urens, Grewia serrulata, Mallotus philippensis, Bridelia retusa, Aphania rubra, Leea indica, L. umbraculifera and Syzygium spp., dominates the landscape (Jain & Sastry 1983).

The key aspect of Kaziranga National Park is that it is home to the largest population of the Indian one-horned rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis), as well as the endangered Asiatic wild water buffalo (Bubalus arnee), elephant, gaur, sambar and eastern swamp deer (Cervus duvaucelii) (Mathur et al. 2005).

The Bengal tiger and leopard are two of the big cats found in the forests of the park. The Brahmaputra River, which flows through the park, is inhabited by the endangered Ganges River dolphin (Roy 2020). Over 42 species of reptile including the endangered gharial and the rare Assam roofed turtle have been recorded in the national Park. Flocks of migratory birds such as the lesser white-fronted goose, ferruginous duck, Baer's pochard, lesser adjutant, greater adjutant, black-necked stork and Asian openbill stork pay seasonal visits to the heritage site (Puri & Joshi 2018; Roy 2020). A study of the turtle fauna of Kaziranga National Park revealed the presence of 14 species in the beels and swampy lakes of the park (Basumatary & Sharma 2013).

Recognized as a forest reserve in 1905, Kaziranga National Park was inscribed as a Natural World Heritage Site in 1985 (Mathur et al. 2005). It is located in Golaghat, Nagaon and Karbi-Anglong districts, of Assam (between longitudes 92° 50' E and 93° 41' E and latitudes 26° 30' N and 26° 50' N) (Roy 2020). It has an extent of 430 km2 (Barua & Sharma 1999). The park experiences three distinct seasons: summer, monsoon and winter. The summer is generally dry and windy and lasts from mid- February to May, with high temperatures of 37°C being reached. The monsoon (May–September) is warm and humid. The annual rainfall of 2220 mm is received mostly during the monsoon. In winter (November to mid-February), the temperature can go as low as 5°C, with the mean maximum temperature being 25°C. The climate remains dry throughout the season (Roy 2020). The eastern and western areas of the park are at different altitudes (40-80 m) (Roy 2020).

Kaziranga National Park is known for its unique habitats and remarkable biodiversity. The western region of the park is dominated by grasslands, with tall grasses, known as elephant grass, on the higher lands, and short grasses on the lower lands. These grasslands are also found on the the sandy riverine tract of the Brahmaputra and support a rich biodiversity (Chakrabarty et al. 2019). The vegetation is broadly classified into four primary categories: (1) eastern wet alluvial grassland; (2) eastern Dillenia swamp forest; (3) riparian fringing forest; and (4) Assam alluvial plains semi-evergreen forest (Champion & Seth 1968). A wide variety of evergreen and deciduous trees, including Aphanamixis polystachya, Talauma hodgsonii, Dillenia indica, Garcinia tinctoria, Ficus rumphii, Cinnamomum bejolghota, Albizia procera, Duabanga grandiflora, Lagerstroemia speciosa, Crateva unilocularis, Sterculia urens, Grewia serrulata, Mallotus philippensis, Bridelia retusa, Aphania rubra, Leea indica, L. umbraculifera and Syzygium spp., dominates the landscape (Jain & Sastry 1983).

The key aspect of Kaziranga National Park is that it is home to the largest population of the Indian one-horned rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis), as well as the endangered Asiatic wild water buffalo (Bubalus arnee), elephant, gaur, sambar and eastern swamp deer (Cervus duvaucelii) (Mathur et al. 2005).

The Bengal tiger and leopard are two of the big cats found in the forests of the park. The Brahmaputra River, which flows through the park, is inhabited by the endangered Ganges River dolphin (Roy 2020). Over 42 species of reptile including the endangered gharial and the rare Assam roofed turtle have been recorded in the national Park. Flocks of migratory birds such as the lesser white-fronted goose, ferruginous duck, Baer's pochard, lesser adjutant, greater adjutant, black-necked stork and Asian openbill stork pay seasonal visits to the heritage site (Puri & Joshi 2018; Roy 2020). A study of the turtle fauna of Kaziranga National Park revealed the presence of 14 species in the beels and swampy lakes of the park (Basumatary & Sharma 2013).

Criterion (ix)

River fluctuations by the Brahmaputra River system result in spectacular examples of riverine and fluvial processes. River bank erosion, sedimentation and formation of new lands as well as new water-bodies, plus succession between grasslands and woodlands represents outstanding examples of significant and ongoing, dynamic ecological and biological processes. Wet alluvial grasslands occupy nearly two-thirds of the park area and are maintained by annual flooding and burning. These natural processes create complexes of habitats which are also responsible for a diverse range of predator/prey relationships.

River fluctuations by the Brahmaputra River system result in spectacular examples of riverine and fluvial processes. River bank erosion, sedimentation and formation of new lands as well as new water-bodies, plus succession between grasslands and woodlands represents outstanding examples of significant and ongoing, dynamic ecological and biological processes. Wet alluvial grasslands occupy nearly two-thirds of the park area and are maintained by annual flooding and burning. These natural processes create complexes of habitats which are also responsible for a diverse range of predator/prey relationships.

Criterion (x)

Kaziranga was inscribed for being the world’s major stronghold of the Indian one-horned rhino, having the single largest population of this species, currently estimated at over 2,000 animals. The property also provides habitat for a number of globally threatened species including tiger, Asian elephant, wild water buffalo, gaur, eastern swamp deer, Sambar deer, hog deer, capped langur, hoolock gibbon and sloth bear. The Park has recorded one of the highest densities of tiger in the country and has been declared a Tiger Reserve since 2007. The park’s location at the junction of the Australasia and Indo-Asian flyway means that the park’s wetlands play a crucial role for the conservation of globally threatened migratory bird species. The Endangered Ganges dolphin is also found in some of the closed oxbow lakes.

Status

Kaziranga National Park is well known for sheltering the largest population of the Indian onehorned Rhinoceros in the world (60%) (Mathur et al. 2005). The park draws tourists and researchers from around the world (Roy 2020). In 1937, it was decided to allow visitors inside Kaziranga National Park. Elephant and vehicle safaris were permitted in order to promote wildlife awareness. The state government has been implementing several initiatives to promote ecotourism and making efforts to manage the large influx of foreign and local tourists (Roy 2020). A survey conducted on the tourism at Kaziranga National Park concluded that the site has been suffering from over-exposure over the years. Tourism infrastructure (almost 70 private and public hotels) is reported to occupy a large area in the southern part of the heritage site (Bharali & Mazumdar 2012). In 2005–06, the total number of tourists 54,326, and the number had increased considerably to 177,431 in 2017–18 (Patnaik et al. 2019).

Kaziranga National Park was the first area in Assam to be notified, in 1908, a rhino conservation region (Puri & Joshi 2018). However, poaching of the one-horned rhinos is one of the most devastating threats impacting the World Heritage Site (MEE 2007; State Party of India 2008; IUCN 2020). The horns of rhinos are considered in foreign culture to have alleged aphrodisiac qualities and medicinal properties (Kushwaha et al. 2000). Conserving rhinos is an ongoing relentless fight with poachers and smugglers (Vigne& Martin 1998; Talukdar 2000).

Human-wildlife conflicts have been taking place at the edge since urbanization and road construction began in the buffer zone of Kaziranga National Park. Settlements have been coming up increasingly along the sides of NH-37. This has led to other activities such as expansion of agriculture land, fodder and firewood collection, construction of roads, market complexes and restaurants, etc. (Kushwaha et al. 2000). This has resulted in incidences of human–wildlife conflicts surrounding the human population encroaches upon the natural habitats.

Kaziranga National Park is well known for the annual flooding of the Brahmaputra River and its tributaries. The floods not only affect the unique ecosystem of the park, including the grasslands, swamps and lakes, but also the wildlife. The floods make the animals more vulnerable to poaching and road-kills as they try to cross NH-37 to reach higher ground. A survey recorded 68 instances of road kills of reptiles belonging to 21 species and seven families (Das et al. 2007). This highlights the importance of effective flood management and monitoring of the park to protect its unique ecosystem and the wildlife that it supports.

Another factor affecting the heritage site is invasion of the grasslands of the park by alien species. Mimosa diplotricha has occupied most areas of the park, mainly Bagori Range, diminishing the grassland cover and impacting the movements as well as food sources of the rhinos and other herbivores (Lahkar et al. 2011). The park authorities, and later Wildlife Trust of India, with the help of the forest department, uprooted much of this weed. The success was low as the uprooting operation was not continuous and tprobably inadequate (Lahkar et al. 2011).

The State Party (India) has been in constant communication with the Assam State Government to monitor the concerns effectively in order to conserve the World Heritage Site. The poaching-threatened endangered one-horned rhinoceros and other endemic species are protected by the Wildlife Protection Act (1972) (Puri& Joshi 2018). In 2007, the site was declared the Kaziranga Tiger Reserve, and measures were implemented that included the installation of the ‘electronic eye’ electronic surveillance system (funded by National Tiger Conservation Authority, Govt. of India). With the bringing in of stringent penalties and issuing of permissions to deal with poachers with firearms (under section 197 (2) of CrPC, 1973), the cases of poaching have been declining significantly (Singh 2007).

The authorities of Kaziranga National Park have been working to improve the situation in this remarkable heritage site with help from the state government, central government, UNESCO and advisory bodies. Local communities have been involved in the management of the park. Reports and assessments have mentioned that Kaziranga National Park is one of the well-managed parks in India; however, its management still requires to be improved, and it needs financial and technical support. Sustainable community strategies, awareness and education programmes and adequate planning are needed (UNEP-WCMC 2011). IUCN assessed Kaziranga National Park to be “Good with some concerns” in 2020.

Kaziranga National Park is well known for sheltering the largest population of the Indian onehorned Rhinoceros in the world (60%) (Mathur et al. 2005). The park draws tourists and researchers from around the world (Roy 2020). In 1937, it was decided to allow visitors inside Kaziranga National Park. Elephant and vehicle safaris were permitted in order to promote wildlife awareness. The state government has been implementing several initiatives to promote ecotourism and making efforts to manage the large influx of foreign and local tourists (Roy 2020). A survey conducted on the tourism at Kaziranga National Park concluded that the site has been suffering from over-exposure over the years. Tourism infrastructure (almost 70 private and public hotels) is reported to occupy a large area in the southern part of the heritage site (Bharali & Mazumdar 2012). In 2005–06, the total number of tourists 54,326, and the number had increased considerably to 177,431 in 2017–18 (Patnaik et al. 2019).

Kaziranga National Park was the first area in Assam to be notified, in 1908, a rhino conservation region (Puri & Joshi 2018). However, poaching of the one-horned rhinos is one of the most devastating threats impacting the World Heritage Site (MEE 2007; State Party of India 2008; IUCN 2020). The horns of rhinos are considered in foreign culture to have alleged aphrodisiac qualities and medicinal properties (Kushwaha et al. 2000). Conserving rhinos is an ongoing relentless fight with poachers and smugglers (Vigne& Martin 1998; Talukdar 2000).

Human-wildlife conflicts have been taking place at the edge since urbanization and road construction began in the buffer zone of Kaziranga National Park. Settlements have been coming up increasingly along the sides of NH-37. This has led to other activities such as expansion of agriculture land, fodder and firewood collection, construction of roads, market complexes and restaurants, etc. (Kushwaha et al. 2000). This has resulted in incidences of human–wildlife conflicts surrounding the human population encroaches upon the natural habitats.

Kaziranga National Park is well known for the annual flooding of the Brahmaputra River and its tributaries. The floods not only affect the unique ecosystem of the park, including the grasslands, swamps and lakes, but also the wildlife. The floods make the animals more vulnerable to poaching and road-kills as they try to cross NH-37 to reach higher ground. A survey recorded 68 instances of road kills of reptiles belonging to 21 species and seven families (Das et al. 2007). This highlights the importance of effective flood management and monitoring of the park to protect its unique ecosystem and the wildlife that it supports.

Another factor affecting the heritage site is invasion of the grasslands of the park by alien species. Mimosa diplotricha has occupied most areas of the park, mainly Bagori Range, diminishing the grassland cover and impacting the movements as well as food sources of the rhinos and other herbivores (Lahkar et al. 2011). The park authorities, and later Wildlife Trust of India, with the help of the forest department, uprooted much of this weed. The success was low as the uprooting operation was not continuous and tprobably inadequate (Lahkar et al. 2011).

The State Party (India) has been in constant communication with the Assam State Government to monitor the concerns effectively in order to conserve the World Heritage Site. The poaching-threatened endangered one-horned rhinoceros and other endemic species are protected by the Wildlife Protection Act (1972) (Puri& Joshi 2018). In 2007, the site was declared the Kaziranga Tiger Reserve, and measures were implemented that included the installation of the ‘electronic eye’ electronic surveillance system (funded by National Tiger Conservation Authority, Govt. of India). With the bringing in of stringent penalties and issuing of permissions to deal with poachers with firearms (under section 197 (2) of CrPC, 1973), the cases of poaching have been declining significantly (Singh 2007).

The authorities of Kaziranga National Park have been working to improve the situation in this remarkable heritage site with help from the state government, central government, UNESCO and advisory bodies. Local communities have been involved in the management of the park. Reports and assessments have mentioned that Kaziranga National Park is one of the well-managed parks in India; however, its management still requires to be improved, and it needs financial and technical support. Sustainable community strategies, awareness and education programmes and adequate planning are needed (UNEP-WCMC 2011). IUCN assessed Kaziranga National Park to be “Good with some concerns” in 2020.