Greater Blue Mountains Area (917)

The Greater Blue Mountains Area is an exceptionally remarkable World Heritage Property that integrates eight major protected areas - Blue Mountains National Park (NP), Wollemi NP, Yengo NP, Garden of Stone NP, Kanangra-Boyd NP, Natti NP, Thirlmere Lakes NP and Jenolan Caves Conservation Reserve. This property is located in New South Wales, on the west coast of Sydney, Australia. Its landscape consists of sandstone tabletop plateaus whose elevation ranges from 20 m near the Nepean River at Glenbrook to over 1330 m at Mount Emperor near Jenolan Caves. The plant species that makes up most of the vegetation cover is Eucalyptus. These gum trees are a characteristic Australian group of species belonging to the Myrtaceae family. Eucalyptus deanei, Eucalyptus saligna, Eucalyptus sclerophylla and Eucalyptus cunninghamii are some of the prominent species at different elevations.

The Greater Blue Mountains Area is an exceptionally remarkable World Heritage Property that integrates eight major protected areas - Blue Mountains National Park (NP), Wollemi NP, Yengo NP, Garden of Stone NP, Kanangra-Boyd NP, Natti NP, Thirlmere Lakes NP and Jenolan Caves Conservation Reserve. This property is located in New South Wales, on the west coast of Sydney, Australia. Its landscape consists of sandstone tabletop plateaus whose elevation ranges from 20 m near the Nepean River at Glenbrook to over 1330 m at Mount Emperor near Jenolan Caves. The plant species that makes up most of the vegetation cover is Eucalyptus. These gum trees are a characteristic Australian group of species belonging to the Myrtaceae family. Eucalyptus deanei, Eucalyptus saligna, Eucalyptus sclerophylla and Eucalyptus cunninghamii are some of the prominent species at different elevations.

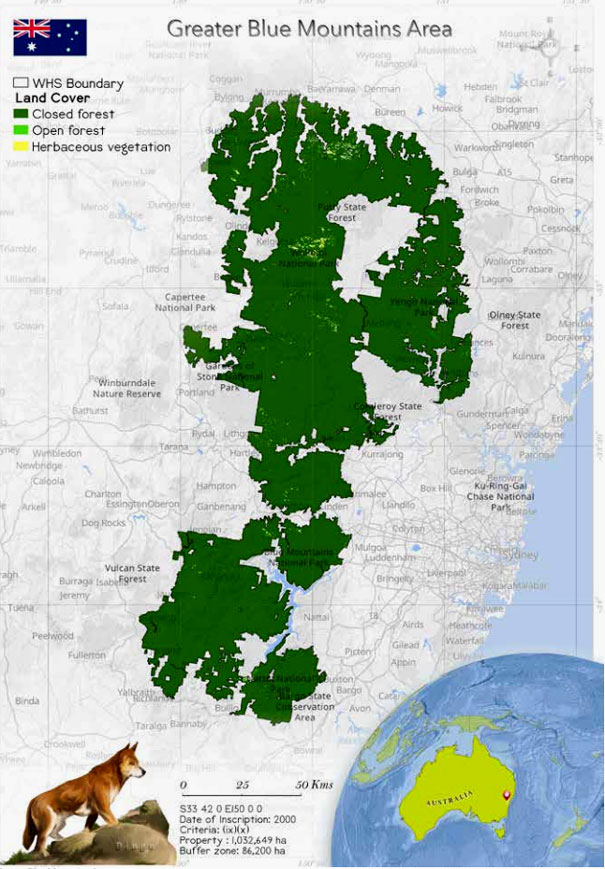

One of the largest protected areas, the Greater Blue Mountains Area is located in New South Wales on the west coast of Sydney, Australia. It encompasses eight significant protected areas - Blue Mountains NP, Wollemi NP, Yengo NP, Garden of Stone NP, Kanangra-Boyd NP, Natti NP, Thirlmere Lakes NP and Jenolan Caves Conservation Reserve (Hager and Benson 2000). The property extends approximately 200 km south from the Hunter Valley to the Southern Tablelands and 35 to 100 km west from the Nepean River to the top of the Great Dividing Range (Smith and Smith 2020).

The elevation of the Greater Blue Mountains Area ranges from 20 m near the Nepean River at Glenbrook to over 1330 m at Mount Emperor near Jenolan Caves. Yengo NP lies at the lowest plateau with extensive areas below 300 m elevation, and the rest of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area (GBMWHA) is generally higher than 400 m. With increase in the altitude, the climate becomes colder and wetter. The Upper Mountains are met by frost, fog and snow (Smith et al. 2019; Hager and Benson 2010). The climate is much warmer in the lower eastern and northern areas (Hager and Benson 2010). Annual rainfall over most of the GBMWHA is moderate (800-1200 mm p.a.), which increases with elevation to 1400 mm p.a. in the central Blue Mountains (Katoomba to Newnes Plateau) and in Kanangra-Boyd NP. However, rainfall progressively decreases north of Newnes Plateau, being lowest in the northwest in northern Wollemi (Hager and Benson 2010).

The Greater Blue Mountains Heritage Site is remarkable for its Eucalyptus-dominated landscape because of which the region represents a substantial portion of Australia's biodiversity (e.g. containing 14% of all eucalypt taxa, and substantial numbers of rare or threatened species, including evolutionary relict species such as the Wollemi pine (Wollemia nobilis) (Chapple et al. 2011; NSW NPWS 2009). The sandstone plateau forest dry sclerophyll vegetation is epitomized by Eucalyptus sieberi and Eucalyptus piperita (National Herbarium 1977). In fact, it is described as a natural laboratory to study the evolution of eucalypts (Hager and Benson 2010).The wide-ranging elevations, geologies, landforms, soils, climatic conditions as well as fire histories have moulded the development of a montage of different types of eucalypt forest and woodland, interspersed with other habitats such as rainforest, heath, swamp, open wetlands, watercourses, cliffs and other rock formations (Smith and Smith 2020).

One of the largest protected areas, the Greater Blue Mountains Area is located in New South Wales on the west coast of Sydney, Australia. It encompasses eight significant protected areas - Blue Mountains NP, Wollemi NP, Yengo NP, Garden of Stone NP, Kanangra-Boyd NP, Natti NP, Thirlmere Lakes NP and Jenolan Caves Conservation Reserve (Hager and Benson 2000). The property extends approximately 200 km south from the Hunter Valley to the Southern Tablelands and 35 to 100 km west from the Nepean River to the top of the Great Dividing Range (Smith and Smith 2020).

The elevation of the Greater Blue Mountains Area ranges from 20 m near the Nepean River at Glenbrook to over 1330 m at Mount Emperor near Jenolan Caves. Yengo NP lies at the lowest plateau with extensive areas below 300 m elevation, and the rest of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area (GBMWHA) is generally higher than 400 m. With increase in the altitude, the climate becomes colder and wetter. The Upper Mountains are met by frost, fog and snow (Smith et al. 2019; Hager and Benson 2010). The climate is much warmer in the lower eastern and northern areas (Hager and Benson 2010). Annual rainfall over most of the GBMWHA is moderate (800-1200 mm p.a.), which increases with elevation to 1400 mm p.a. in the central Blue Mountains (Katoomba to Newnes Plateau) and in Kanangra-Boyd NP. However, rainfall progressively decreases north of Newnes Plateau, being lowest in the northwest in northern Wollemi (Hager and Benson 2010).

The Greater Blue Mountains Heritage Site is remarkable for its Eucalyptus-dominated landscape because of which the region represents a substantial portion of Australia's biodiversity (e.g. containing 14% of all eucalypt taxa, and substantial numbers of rare or threatened species, including evolutionary relict species such as the Wollemi pine (Wollemia nobilis) (Chapple et al. 2011; NSW NPWS 2009). The sandstone plateau forest dry sclerophyll vegetation is epitomized by Eucalyptus sieberi and Eucalyptus piperita (National Herbarium 1977). In fact, it is described as a natural laboratory to study the evolution of eucalypts (Hager and Benson 2010).The wide-ranging elevations, geologies, landforms, soils, climatic conditions as well as fire histories have moulded the development of a montage of different types of eucalypt forest and woodland, interspersed with other habitats such as rainforest, heath, swamp, open wetlands, watercourses, cliffs and other rock formations (Smith and Smith 2020).

Criterion (ix)

The Greater Blue Mountains include outstanding and representative examples in a relatively small area of the evolution and adaptation of the genus Eucalyptus and eucalypt-dominated vegetation on the Australian continent. The site contains a wide and balanced representation of eucalypt habitats including wet and dry sclerophyll forests and mallee heathlands, as well as localized swamps, wetlands and grassland. It is a center of diversification for the Australian scleromorphic flora, including significant aspects of eucalypt evolution and radiation. Representative examples of the dynamic processes in its eucalypt-dominated ecosystems cover the full range of interactions between eucalypts, under-storey, fauna, environment and fire. The site includes primitive species of outstanding significance to the evolution of the earth's plant life, such as the highly restricted Wollemi pine (Wollemia nobilis) and the Blue Mountains pine (Pherosphaera fitzgeraldii). These are examples of ancient, relict species with Gondwanan affinities that have survived past climatic changes and demonstrate the highly unusual juxtaposition of Gondwanan taxa with the diverse scleromorphic flora.

Criterion (x)

The site includes an outstanding diversity of habitats and plant communities that support its globally significant species and ecosystem diversity (152 plant families, 484 genera and c. 1,500 species). A significant proportion of the Australian continent's biodiversity, especially its scleromorphic flora, occur in the area. Plant families represented by exceptionally high levels of species diversity here include Myrtaceae (150 species), Fabaceae (149 species), and Proteaeceae (77 species). Eucalypts (Eucalyptus, Angophora and Corymbia, all in the family Myrtaceae) which dominate the Australian continent are well represented by more than 90 species (13% of the global total). The genus Acacia (in the family Fabaceae) is represented by 64 species. The site includes primitive and relictual species with Gondwanan affinities (Wollemia, Pherosphaera, Lomatia, Dracophyllum, Acrophyllum, Podocarpus andAtkinsonia) and supports many plants of conservation significance including 114 endemic species and 177threatened species.

Status

According to the state of conservation reports by UNESCO of the years 2001, 2004 and 2019, the primary factors affecting the heritage property are mining and pollution of the surface water and aquatic ecosystems. Pollution in the streams and rivers of Greater Blue Mountains Area has also raised concerns in terms of conservation of the World Heritage Site. Historically, the primary source of water pollution in the Blue Mountains Area has been sewage effluent. There were 12 sewage treatment plants (STPs) in the Blue Mountains (MWS&DB 1987) in 1980. By the early 1990s, six STPs disposed of the wastewater into streams that flowed into the National Park estate lands (Berman et al. 1987). For more than a century, water pollution throughout Australia, and in the Blue Mountains Area, has been due to coal mining (Macqueen 2007). To protect the aquatic biodiversity and landscape, many of the mines were closed; however, a few still persist in the Lithgow and upper Coxs Valley area (Lithgow Tourism 2009) in the Western Blue Mountains. The Grose River catchment is located approximately in the centre of the Greater Blue Mountains Area, to the immediate north of the urban corridor that runs between Penrith and Mount Victoria. The Grose River has suffered two different forms of water pollution (Wright et al. 2010). The first is organic pollution from treated sewage effluent from the Blackheath STP (Wright and Burgin 2009), and the second is contaminated drainage from a derelict coal mine, the Canyon Coal Mine (Wright et al. 2010).In 2014, a report on degradation of aquatic ecosystems in the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area pointed fingers at the Clarence Colliery mine which discharges coal mine water into the Wollangambe River, causing pollution-related physical and chemical changes to the water quality as well as changes in macroinvertebrate communities. The waste discharge from the mining operation increased the water temperature, salinity and pH, modified the ionic composition of the river water, and elevated zinc and nickel concentrations to potentially toxic levels (Belmer et al. 2014). According to IUCN's 2020 report, there is major concern about invasive species that have caused havoc in the endemism of the site (IUCN Consultation 2020).