Great Himalayan National Park Conservation Area (1406)

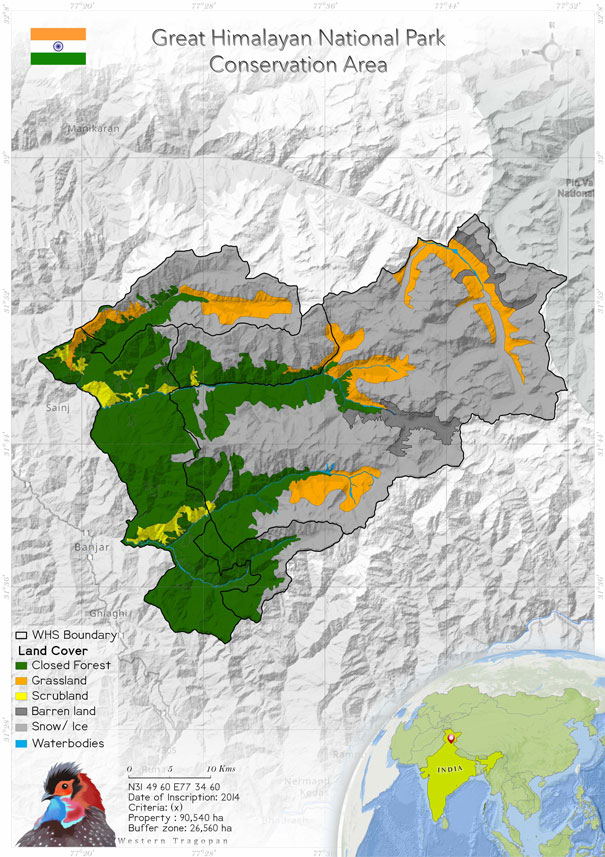

The Great Himalayan National Park Conservation Area (GHNPCA), situated in the western part of the Himalayan Mountains within the northern Indian State of Himachal Pradesh, spans an expansive 90,540 hectares. This protected region plays a crucial role as the source of origin for key rivers including Jiwa Nal, Sainj, Tirthan, and Parvati, all of which are significant headwater tributaries to the Beas River and subsequently, the Indus River. Encompassing a diverse range of elevations, from towering alpine peaks exceeding 6,000 meters above sea level to serene riverine forests below 2,000 meters, the park's conservation area holds immense importance for safeguarding vital water supplies that cater to the needs of millions downstream. Geographically positioned in the unique junction between the Palearctic and Indomalayan Realms, the Great Himalayan National Park Conservation Area boasts an exceptional ecological status within the distinct Western Himalayan landscape. This geographical positioning has bestowed the park with a remarkable diversity of ecosystems, including monsoon-influenced forests and alpine meadows that support a distinctive biota adapted to various altitudinal zones. Many plant and animal species in this region are found nowhere else, underscoring its significance in biodiversity preservation.

The Great Himalayan National Park Conservation Area (GHNPCA), situated in the western part of the Himalayan Mountains within the northern Indian State of Himachal Pradesh, spans an expansive 90,540 hectares. This protected region plays a crucial role as the source of origin for key rivers including Jiwa Nal, Sainj, Tirthan, and Parvati, all of which are significant headwater tributaries to the Beas River and subsequently, the Indus River. Encompassing a diverse range of elevations, from towering alpine peaks exceeding 6,000 meters above sea level to serene riverine forests below 2,000 meters, the park's conservation area holds immense importance for safeguarding vital water supplies that cater to the needs of millions downstream. Geographically positioned in the unique junction between the Palearctic and Indomalayan Realms, the Great Himalayan National Park Conservation Area boasts an exceptional ecological status within the distinct Western Himalayan landscape. This geographical positioning has bestowed the park with a remarkable diversity of ecosystems, including monsoon-influenced forests and alpine meadows that support a distinctive biota adapted to various altitudinal zones. Many plant and animal species in this region are found nowhere else, underscoring its significance in biodiversity preservation.

The Great Himalaya National Park is situated in the state of Himachal Pradesh, in north India, in the western Himalayan Mountains. It is located around 45 km far from Kullu District (Jolli et al. 2012). The upper mountains of the park have glaciers and snow, which provide water to the three river of the park, the Jiwa Nal, Sainj and Tirthan rivers, and to the Parvati river. The property has an altitudinal range from 2000 m asl to 6000 m asl. The Western Himalaya, where the property is located, is situated at the junction of the great Palaearctic and Indomalayan realms (UNESCO whc.unesco.org). The area is covered by large meadows and pastures, and the forest vegetation is lush with subtropical, mixed broadleaf and coniferous trees (Jolli et al. 2012).

In 1999, the park was declared a national park, after which the authorities of GNHP prohibited the extraction of the biomass under the Wildlife (Protection) Act (Chhatre & Saberwal 2005; Pandey & Wells 1997). After the declaration, the management also limited the number of villagers who could enter the park for collecting non-timber forest products, grazing livestock and poaching wildlife (Pandey 2008).

The vegetation in the park consists of alpine scrub, alpine meadows, temperate broadleaf forest, temperate conifer forest, temperate broadleaf conifer mixed forest, sub-alpine forest and temperate grasslands (Champion & Seth 1968). There are 1700 medicinal plants in the park that are used in traditional medicine and in the herbal industry (Chauhan et al. 2018). Birdlife International considers it an important endemic bird area. Being an international conservation hotspot the area supports many restricted-range species (Bibby et al. 1992).

Miller conducted a survey in the GHNPCA from early April to late May in 2008, in which he studied three bird species, the Western tragopan, koklass pheasant and Himalayan monal. During his study, he recorded 32 Western tragopans, 295 koklass pheasants and 115 Himalayan monals. A comparison with a survey conducted in 1990 shows an increase in the relative abundance of the population of each of these bird species (Miller 2010).

The Great Himalaya National Park is situated in the state of Himachal Pradesh, in north India, in the western Himalayan Mountains. It is located around 45 km far from Kullu District (Jolli et al. 2012). The upper mountains of the park have glaciers and snow, which provide water to the three river of the park, the Jiwa Nal, Sainj and Tirthan rivers, and to the Parvati river. The property has an altitudinal range from 2000 m asl to 6000 m asl. The Western Himalaya, where the property is located, is situated at the junction of the great Palaearctic and Indomalayan realms (UNESCO whc.unesco.org). The area is covered by large meadows and pastures, and the forest vegetation is lush with subtropical, mixed broadleaf and coniferous trees (Jolli et al. 2012).

In 1999, the park was declared a national park, after which the authorities of GNHP prohibited the extraction of the biomass under the Wildlife (Protection) Act (Chhatre & Saberwal 2005; Pandey & Wells 1997). After the declaration, the management also limited the number of villagers who could enter the park for collecting non-timber forest products, grazing livestock and poaching wildlife (Pandey 2008).

The vegetation in the park consists of alpine scrub, alpine meadows, temperate broadleaf forest, temperate conifer forest, temperate broadleaf conifer mixed forest, sub-alpine forest and temperate grasslands (Champion & Seth 1968). There are 1700 medicinal plants in the park that are used in traditional medicine and in the herbal industry (Chauhan et al. 2018). Birdlife International considers it an important endemic bird area. Being an international conservation hotspot the area supports many restricted-range species (Bibby et al. 1992).

Miller conducted a survey in the GHNPCA from early April to late May in 2008, in which he studied three bird species, the Western tragopan, koklass pheasant and Himalayan monal. During his study, he recorded 32 Western tragopans, 295 koklass pheasants and 115 Himalayan monals. A comparison with a survey conducted in 1990 shows an increase in the relative abundance of the population of each of these bird species (Miller 2010).

Criterion (x)

The Great Himalayan National Park Conservation Area is located within the globally significant “Western Himalayan Temperate Forests” ecoregion. The property also protects part of Conservation International’s Himalaya “biodiversity hot spot” and is part of the BirdLife International’s Western Himalaya Endemic Bird Area. The Great Himalayan National Park Conservation Area is home to 805 vascular plant species, 192 species of lichen, 12 species of liverworts and 25 species of mosses. Some 58% of its angiosperms are endemic to the Western Himalayas. The property also protects some 31 species of mammals, 209 birds, 9 amphibians, 12 reptiles and 125 insects. The Great Himalayan National Park Conservation Area provides habitat for 4 globally threatened mammals, 3 globally threatened birds and a large number of medicinal plants. The protection of lower altitude valleys provides for more complete protection and management of important habitats and endangered species such as the Western Tragopan and the Musk Deer.

The Great Himalayan National Park Conservation Area is located within the globally significant “Western Himalayan Temperate Forests” ecoregion. The property also protects part of Conservation International’s Himalaya “biodiversity hot spot” and is part of the BirdLife International’s Western Himalaya Endemic Bird Area. The Great Himalayan National Park Conservation Area is home to 805 vascular plant species, 192 species of lichen, 12 species of liverworts and 25 species of mosses. Some 58% of its angiosperms are endemic to the Western Himalayas. The property also protects some 31 species of mammals, 209 birds, 9 amphibians, 12 reptiles and 125 insects. The Great Himalayan National Park Conservation Area provides habitat for 4 globally threatened mammals, 3 globally threatened birds and a large number of medicinal plants. The protection of lower altitude valleys provides for more complete protection and management of important habitats and endangered species such as the Western Tragopan and the Musk Deer.

Status

In the south-western side of the park, an extent of around 26,560 ha is considered the ecozone, where the increasing human population pressure is felt. However, according to the State of Conservation Report 2019, the state party has proposed enhancing the area of the site by including Pin Valley, Kheerganaga National Park, Rupi Bhaba and Kanawar Wildlife Sanctuary. The World Heritage Committee did support the vision, recommending that the State Party take guidance from the IUCN and the World Heritage Center on the extension of the property (State of Conservation Report 2019).

The local communities are reported to support the management and to be involved in the taking of management decisions. To enhance and improve the community support, the communities need to be fully empowered (UNESCO whc.unesco.org). The local people living in the park have traditionally been dependent on its resources and earn their livelihoods from the resources. The economy of these people is based on agriculture, livestock and minor forest products (Nangia & Kumar 2001). The locals have access restrictions in the park so that the integrity of the property is maintained. However, to provide alternative livelihood options, various activities have been carried out in the park, such as interaction with Women Self Help Groups to support alternative livelihood options, such as having dialogues with and providing guidance for local tourism operators. Diverse capacity development efforts are being made in collaboration with the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) (State of Conservation Report 2019).

Sainj Wildlife Sanctuary, which is part of the property, has around 120 residents (Nangia et al. 1999; UNESCO whc.unesco.org), and Tirthan Wildlife Sanctuary is uninhabited at present, but traditional grazing practices are carried out in the valley. These two sanctuary are part of the property, as a result of which its integrity is certainly improved, but this also raises concerns about the effects of grazing and human settlement on the universal values of the site. Thus the issue of high pasture grazing in Tirthan and the impact of the human settlement in Sainj need to be addressed (UNESCO whc. unesco.org).

In the south-western side of the park, an extent of around 26,560 ha is considered the ecozone, where the increasing human population pressure is felt. However, according to the State of Conservation Report 2019, the state party has proposed enhancing the area of the site by including Pin Valley, Kheerganaga National Park, Rupi Bhaba and Kanawar Wildlife Sanctuary. The World Heritage Committee did support the vision, recommending that the State Party take guidance from the IUCN and the World Heritage Center on the extension of the property (State of Conservation Report 2019).

The local communities are reported to support the management and to be involved in the taking of management decisions. To enhance and improve the community support, the communities need to be fully empowered (UNESCO whc.unesco.org). The local people living in the park have traditionally been dependent on its resources and earn their livelihoods from the resources. The economy of these people is based on agriculture, livestock and minor forest products (Nangia & Kumar 2001). The locals have access restrictions in the park so that the integrity of the property is maintained. However, to provide alternative livelihood options, various activities have been carried out in the park, such as interaction with Women Self Help Groups to support alternative livelihood options, such as having dialogues with and providing guidance for local tourism operators. Diverse capacity development efforts are being made in collaboration with the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) (State of Conservation Report 2019).

Sainj Wildlife Sanctuary, which is part of the property, has around 120 residents (Nangia et al. 1999; UNESCO whc.unesco.org), and Tirthan Wildlife Sanctuary is uninhabited at present, but traditional grazing practices are carried out in the valley. These two sanctuary are part of the property, as a result of which its integrity is certainly improved, but this also raises concerns about the effects of grazing and human settlement on the universal values of the site. Thus the issue of high pasture grazing in Tirthan and the impact of the human settlement in Sainj need to be addressed (UNESCO whc. unesco.org).