Chitwan National Park (284)

Chitwan, heart of the jungle, is Nepal's first national park and one of the most popular tourism sites. Situated at the foot of the Himalaya, Chitwan is home to many plants and animals, including the one-horned rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) and the majestic Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris). The forests of Chitwan are dominated by sal (Shorea robusta), and its grasslands have the tallest grasses of the world, Saccharum ravennae, Arundo donax, etc. The Bengal florican (Houbaropsis bengalensis) and lesser adjutant (Leptoptilos javanicus) are resident birds of the natQional park, which is also visited by migrating birds in the winter and in the summer. The mugger crocodile, gharial and other reptiles and amphibians are also found in the national park. The riverine system, forest succession and grassland patches are constanly changing due to floods during the monsoon. The national park is facing many challenges such as poaching of threatened species, pollution, negative impacts of tourism, encroachment activities and development and urbanization. The State Party has been taking important measures that are required to face these challenges and to maintain the Outstanding Universal Valueof Chitwan National Park. Threats faced by the national park include poaching of rhinos, invasive species and development of transport infrastructure.

Chitwan, heart of the jungle, is Nepal's first national park and one of the most popular tourism sites. Situated at the foot of the Himalaya, Chitwan is home to many plants and animals, including the one-horned rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) and the majestic Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris). The forests of Chitwan are dominated by sal (Shorea robusta), and its grasslands have the tallest grasses of the world, Saccharum ravennae, Arundo donax, etc. The Bengal florican (Houbaropsis bengalensis) and lesser adjutant (Leptoptilos javanicus) are resident birds of the natQional park, which is also visited by migrating birds in the winter and in the summer. The mugger crocodile, gharial and other reptiles and amphibians are also found in the national park. The riverine system, forest succession and grassland patches are constanly changing due to floods during the monsoon. The national park is facing many challenges such as poaching of threatened species, pollution, negative impacts of tourism, encroachment activities and development and urbanization. The State Party has been taking important measures that are required to face these challenges and to maintain the Outstanding Universal Valueof Chitwan National Park. Threats faced by the national park include poaching of rhinos, invasive species and development of transport infrastructure.

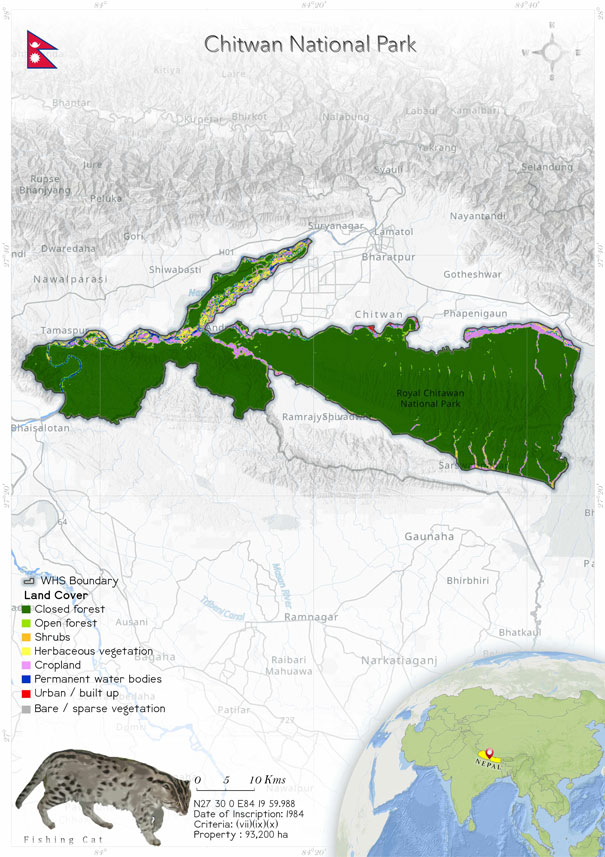

Situated at the foothills of the Himalaya, Chitwan National Park is the first protected area of Nepal. Chitwan used to be a favorite hunting site for the royals of Nepal, and tigers, rhinoceroses, leopards and sloth bears were hunted excessively. The excessive hunting and killing led to decreasing populations of these magnificent animals. The government established Chitwan National Park in 1973 under the National Parks and Wildlife Act to prevent the complete extinction of the last population of the one-horned Asiatic rhinoceros. It is among the few undisturbed fragment of the Terai regions and has an extremely rich flora and fauna. The park covers an area of 93,200 ha, extending over the four districts of Nepal—Chitwan, Nawalparasi, Parsa and Makwanpur. The Narayani (Gandak) and Rapti rivers, in the north, drain the core area of the national park. The national park shares an international border with India and is lined by the Reu River in the south. The park also shares its boundary with another protected area, Parsa Wildlife Reserve, in the east. A buffer zone of 75,000 ha was declared in 1996. This buffer zone includes surrounding forests and private lands. The park is centred around 27o 20' 40" N, 83o 82' 45" E. Beeshazar lake and other associated lakes situated inside the buffer zone were declared a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar Convention in 2003.

Chitwan has a highly humid monsoon bringing 2400 mm of rainfall. Temperatures go up to 38°C during this season, and after the monsoon is over, the temperature falls down to a minimum of 6°C. Shorea robusta or sal covers about 70% and is the dominating vegetation of the national park. The changing course of the river due to floods also continuously changes the forest succession and grassland mosaic. About 20% of the site’s area is covered by savanna and grassland. The grassland has some of the world’s tallest grasses, such as Saccharum ravennae, Arundo donax, Phragmites karka and many true grasses species. Saccharum spontaneum, or kans grass, and Persicaria spp. are among the first grasses on new sandbanks and are the first ones to be removed by early floods (Shrestha et al. 2006).

According to the Chitwan National Park office, the park is home to around 68 mammal species. The World Heritage Site is home to one of the last populations of the one-horned Asiatic rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) and is also the refuge of the majestic Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris). Along with these two, many other threatened animals are found in the national park, such as the Chinese pangolin (Manis pentadactyla), hispid hare (Caprolagus hispidus), sloth bear (Melursus ursinus), smooth-coated otter (Lutrogale perspicillata) and sambar (Rusa unicolor) (Shrestha 2001). The Indian leopard (Panthera pardus) can also be seen on the periphery of the park, coexisting with the tiger (McDougal 1988). According to the National Red List Series (Jnawali et al. 2011), the park has the highest population density of sloth bear. Chitwan National Park has the highest recorded number of birds compared with any other protected area of the country. nearly 565 bird species, including 22 threatened (Poudyal & Nepal 2010). The grasslands of the site are important habitats for threatened bird species, such as the Bengal florican (Houbaropsis bengalensis) and lesser adjutant (Leptoptilos javanicus). The national park is visited by many migrating birds during the winter and the summer. Forty-seven species of reptile including the king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah), Indian python (Python molurus) and common krait (Bungarus caeruleus) are found in the national park (Shrestha 2001). The mugger crocodile (Crocodylus palustris) and gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) are found in the Narayani–Rapti river system of Chitwan.

Chitwan was inhabited by the Tharu community, but when it was declared a protected area, the people were forced to leave their villages and relocate. The Nepalese armed forces were also involved in the removal of the community. Now the buffer zone area of the national park is densely populated, and the population not only includes Tharus but also settlers from the hills. The area south of the Rapti River is the last habitat of the tiger, rhinoceros and gharial, but it is also an area that is densely populated by humans.

Situated at the foothills of the Himalaya, Chitwan National Park is the first protected area of Nepal. Chitwan used to be a favorite hunting site for the royals of Nepal, and tigers, rhinoceroses, leopards and sloth bears were hunted excessively. The excessive hunting and killing led to decreasing populations of these magnificent animals. The government established Chitwan National Park in 1973 under the National Parks and Wildlife Act to prevent the complete extinction of the last population of the one-horned Asiatic rhinoceros. It is among the few undisturbed fragment of the Terai regions and has an extremely rich flora and fauna. The park covers an area of 93,200 ha, extending over the four districts of Nepal—Chitwan, Nawalparasi, Parsa and Makwanpur. The Narayani (Gandak) and Rapti rivers, in the north, drain the core area of the national park. The national park shares an international border with India and is lined by the Reu River in the south. The park also shares its boundary with another protected area, Parsa Wildlife Reserve, in the east. A buffer zone of 75,000 ha was declared in 1996. This buffer zone includes surrounding forests and private lands. The park is centred around 27o 20' 40" N, 83o 82' 45" E. Beeshazar lake and other associated lakes situated inside the buffer zone were declared a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar Convention in 2003.

Chitwan has a highly humid monsoon bringing 2400 mm of rainfall. Temperatures go up to 38°C during this season, and after the monsoon is over, the temperature falls down to a minimum of 6°C. Shorea robusta or sal covers about 70% and is the dominating vegetation of the national park. The changing course of the river due to floods also continuously changes the forest succession and grassland mosaic. About 20% of the site’s area is covered by savanna and grassland. The grassland has some of the world’s tallest grasses, such as Saccharum ravennae, Arundo donax, Phragmites karka and many true grasses species. Saccharum spontaneum, or kans grass, and Persicaria spp. are among the first grasses on new sandbanks and are the first ones to be removed by early floods (Shrestha et al. 2006).

According to the Chitwan National Park office, the park is home to around 68 mammal species. The World Heritage Site is home to one of the last populations of the one-horned Asiatic rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) and is also the refuge of the majestic Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris). Along with these two, many other threatened animals are found in the national park, such as the Chinese pangolin (Manis pentadactyla), hispid hare (Caprolagus hispidus), sloth bear (Melursus ursinus), smooth-coated otter (Lutrogale perspicillata) and sambar (Rusa unicolor) (Shrestha 2001). The Indian leopard (Panthera pardus) can also be seen on the periphery of the park, coexisting with the tiger (McDougal 1988). According to the National Red List Series (Jnawali et al. 2011), the park has the highest population density of sloth bear. Chitwan National Park has the highest recorded number of birds compared with any other protected area of the country. nearly 565 bird species, including 22 threatened (Poudyal & Nepal 2010). The grasslands of the site are important habitats for threatened bird species, such as the Bengal florican (Houbaropsis bengalensis) and lesser adjutant (Leptoptilos javanicus). The national park is visited by many migrating birds during the winter and the summer. Forty-seven species of reptile including the king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah), Indian python (Python molurus) and common krait (Bungarus caeruleus) are found in the national park (Shrestha 2001). The mugger crocodile (Crocodylus palustris) and gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) are found in the Narayani–Rapti river system of Chitwan.

Chitwan was inhabited by the Tharu community, but when it was declared a protected area, the people were forced to leave their villages and relocate. The Nepalese armed forces were also involved in the removal of the community. Now the buffer zone area of the national park is densely populated, and the population not only includes Tharus but also settlers from the hills. The area south of the Rapti River is the last habitat of the tiger, rhinoceros and gharial, but it is also an area that is densely populated by humans.

Criterion (vii)

The spectacular landscape, covered with lush vegetation and the Himalayas as the backdrop makes the park an area of exceptional natural beauty. The forested hills and changing river landscapes serve to make Chitwan one of the most stunning and attractive parts of Nepal’s lowlands. Situated in a river valley basin and characterized by steep cliffs on the south-facing slopes and a mosaic of riverine forest and grasslands along the river banks of the natural landscape makes the property amongst the most visited tourist destination of its kind in the region. The property includes the Narayani (Gandaki) river, the third-largest river in Nepal which originates in the high Himalayas and drains into the Bay of Bengal providing dramatic river views and scenery as well as the river terraces composed of layers of boulders and gravels. The property includes two famous religious areas: Bikram Baba at Kasara and Balmiki Ashram in Tribeni, pilgrimage places for Hindus from nearby areas and India. This is also the land of the indigenous Tharu community who have inhabited the area for centuries and are well known for their unique cultural practices.

The spectacular landscape, covered with lush vegetation and the Himalayas as the backdrop makes the park an area of exceptional natural beauty. The forested hills and changing river landscapes serve to make Chitwan one of the most stunning and attractive parts of Nepal’s lowlands. Situated in a river valley basin and characterized by steep cliffs on the south-facing slopes and a mosaic of riverine forest and grasslands along the river banks of the natural landscape makes the property amongst the most visited tourist destination of its kind in the region. The property includes the Narayani (Gandaki) river, the third-largest river in Nepal which originates in the high Himalayas and drains into the Bay of Bengal providing dramatic river views and scenery as well as the river terraces composed of layers of boulders and gravels. The property includes two famous religious areas: Bikram Baba at Kasara and Balmiki Ashram in Tribeni, pilgrimage places for Hindus from nearby areas and India. This is also the land of the indigenous Tharu community who have inhabited the area for centuries and are well known for their unique cultural practices.

Criterion (vii)

Constituting the largest and least disturbed example of sal forest and associated communities, Chitwan National Park is an outstanding example of biological evolution with a unique assemblage of native flora and fauna from the Siwalik and inner Terai ecosystems. The property includes the fragile Siwalik-hill ecosystem, covering some of the youngest examples of this as well as alluvial flood plains, representing examples of ongoing geological processes. The property is the last major surviving example of the natural ecosystems of the Terai and has witnessed minimal human impacts from the traditional resource dependency of people, particularly the aboriginal Tharu community living in and around the park.

Criterion (x)

The combination of alluvial flood plains and riverine forest provides an excellent habitat for the Great One-horned Rhinoceros and the property is home for the second largest population of this species in the world. It is also prime habitat for the Bengal Tiger and supports a viable source population of this endangered species. Exceptionally high in species diversity, the park harbours 31% of mammals, 61% of birds, 34% of amphibians and reptiles, and 65% of fishes recorded in Nepal. Additionally, the park is famous for having one of the highest concentrations of birds in the world (over 350 species) and is recognized as one of the worlds’ biodiversity hotspots as designated by Conservation International and falls amongst WWFs’ 200 Global Eco-regions.

Status

Nepal's first national park, Chitwan, was inscribed as World Heritage Site in 1984. The national park has an amazing biological diversity. Being the last refuge of the one-horned rhinoceros and Bengal tiger and being a site with breathtakingly beautiful river landscapes and lush green hills make it a site with outstanding universal value. Kadhka et al. (2017), in January 2016, provided photographic evidence of the hispid hare (Caprolagus hispidus). The hare was sighted after almost thirty years. The first known records of Boiga siamensis and Lycodon striatus were also documented from the national park (Pandey et al. 2018).

Hosting one of the last populations of the one-horned rhinoceros and other threatened species comes with a price. All these threatened animals are under danger of poaching and are been killed by hunters. According to the officials, all rhino deaths had been of natural causes before this and no poaching had been observed since 28 April 2017. Effective management practices resulted in increases in the numbers of rhinos and tigers. In 2018, Nepal became the first country to double its tiger population (235 adult tigers; only 121 in 2009) (DNPWC). Ghimire (2019) conducted a survey in the Kumroj Buffer Zone Community Forest (KBZCF), in Chitwan, and found that 53% of the survey respondents accepted the idea that human–wildlife conflict had been increasing. More than 65% of the respondents agreed that fencing the park would be effective in preventing conflict. Lamichhane et al. (2017) concluded that only a minor fraction (<5%) of the total tiger population that lives in close proximity to humans is problematic and is involved in human–tiger Conflict (HTC). Patrolling, along with real-time monitoring using technical tools such as MIST and SMART, showed positive results as a decline in poaching activities was observed (Mahatara et al. 2018). An early warning system and removal of this minor section of tigers were suggested to avoid HTC (Lamichhane et al. 2017). Despite wildlife attacks, respondents provided positive feedback to wildlife conservation (Ghimire 2019). Chitwan National Park has a compensation scheme for the victims of human-wildlife conflict, which includes human killing, human injuries and livestock depredation (Dhungana et al. 2016).

A review of the State of Conservation (SoC) reports of 18 years showed that the State Party is actively working on creating and implementing measures to protect the Outstanding Universal Value of the national park. The State Party has made the concerned ministries and departments aware about the listing of the site as "In Danger" in the World Heritage List if proper measures are not taken to protect the OUV of the site. The park authorities have suggested that collaboration with the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau (WCCB) will help curb this problem further. Modern technologies such as SMART, drones and CCTV are also being used for constant surveillance of the park. The comments and recommendations made by the IUCN on the EIA of the Balmiki Ashram-Trivenidham Suspension Bridge have been taken cognizance of by the concerned departments'. The proposed China-India Trade Links of State 3 and State 4, Madi–Balmiki Ashram road and Malekhu–Thori road are still projects posing a threat to the OUV of the heritage site, in accordance with Paragragh 180 of the Operational Guidelines. The Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation (DNPWC) has opposed these projects and is still opposing them, but the State Party has not followed the committee's request to not allow the Terai Hulaki Highway to pass through the site. Gajendra Dham, one of the most important holy places of Nepal, lies in the buffer zone of Chitwan National Park, occupying approximately 0.0818 km2. The boundaries were revised by Gajendra Dham on the ground using GPS coordinates. But the revision of the boundaries was not submitted for a review by the World Heritage Committee, as required in the Operational Guidelines. The State Party has been asked to provide clarifications on the revised boundaries to the Committee. The evaluation by IUCN World Heritage Outlook of heritage sites revealed that although the Chitwan National Park authorities were successful in effective conservation practices, threats such as pollution, mass tourism, invasive and alien species and new infrastructure inside, adjacent to or outside the national park still pose a great threat to the World Heritage Value of the park and the site still remains vulnerable. The rising populations of rhinos and tigers show that the World Heritage Values are being maintained. But there is no management whatsoever of the aquatic habitats in the park. The management and protection regime has shown increasing benefits, but still Chitwan National Park is facing many challenges. The authorities are doing their best to maintain the effective regime and management even though their main concerns are the megafauna (large animals such as the rhino and tiger). More attention needs to be given to aquatic animals such as otters and the fishing cat.

The overall picture of Chitwan National Park reveals that the inscription of the national park in the World Heritage List has aided in the protection and conservation of the fauna and flora of the park. The inscription has helped the national park to take effective measures for the conservation, policy and law making involved in protecting the OUV of the World Heritage Site. It has also helped international cooperation, scientific research and monitoring.

Nepal's first national park, Chitwan, was inscribed as World Heritage Site in 1984. The national park has an amazing biological diversity. Being the last refuge of the one-horned rhinoceros and Bengal tiger and being a site with breathtakingly beautiful river landscapes and lush green hills make it a site with outstanding universal value. Kadhka et al. (2017), in January 2016, provided photographic evidence of the hispid hare (Caprolagus hispidus). The hare was sighted after almost thirty years. The first known records of Boiga siamensis and Lycodon striatus were also documented from the national park (Pandey et al. 2018).

Hosting one of the last populations of the one-horned rhinoceros and other threatened species comes with a price. All these threatened animals are under danger of poaching and are been killed by hunters. According to the officials, all rhino deaths had been of natural causes before this and no poaching had been observed since 28 April 2017. Effective management practices resulted in increases in the numbers of rhinos and tigers. In 2018, Nepal became the first country to double its tiger population (235 adult tigers; only 121 in 2009) (DNPWC). Ghimire (2019) conducted a survey in the Kumroj Buffer Zone Community Forest (KBZCF), in Chitwan, and found that 53% of the survey respondents accepted the idea that human–wildlife conflict had been increasing. More than 65% of the respondents agreed that fencing the park would be effective in preventing conflict. Lamichhane et al. (2017) concluded that only a minor fraction (<5%) of the total tiger population that lives in close proximity to humans is problematic and is involved in human–tiger Conflict (HTC). Patrolling, along with real-time monitoring using technical tools such as MIST and SMART, showed positive results as a decline in poaching activities was observed (Mahatara et al. 2018). An early warning system and removal of this minor section of tigers were suggested to avoid HTC (Lamichhane et al. 2017). Despite wildlife attacks, respondents provided positive feedback to wildlife conservation (Ghimire 2019). Chitwan National Park has a compensation scheme for the victims of human-wildlife conflict, which includes human killing, human injuries and livestock depredation (Dhungana et al. 2016).

A review of the State of Conservation (SoC) reports of 18 years showed that the State Party is actively working on creating and implementing measures to protect the Outstanding Universal Value of the national park. The State Party has made the concerned ministries and departments aware about the listing of the site as "In Danger" in the World Heritage List if proper measures are not taken to protect the OUV of the site. The park authorities have suggested that collaboration with the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau (WCCB) will help curb this problem further. Modern technologies such as SMART, drones and CCTV are also being used for constant surveillance of the park. The comments and recommendations made by the IUCN on the EIA of the Balmiki Ashram-Trivenidham Suspension Bridge have been taken cognizance of by the concerned departments'. The proposed China-India Trade Links of State 3 and State 4, Madi–Balmiki Ashram road and Malekhu–Thori road are still projects posing a threat to the OUV of the heritage site, in accordance with Paragragh 180 of the Operational Guidelines. The Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation (DNPWC) has opposed these projects and is still opposing them, but the State Party has not followed the committee's request to not allow the Terai Hulaki Highway to pass through the site. Gajendra Dham, one of the most important holy places of Nepal, lies in the buffer zone of Chitwan National Park, occupying approximately 0.0818 km2. The boundaries were revised by Gajendra Dham on the ground using GPS coordinates. But the revision of the boundaries was not submitted for a review by the World Heritage Committee, as required in the Operational Guidelines. The State Party has been asked to provide clarifications on the revised boundaries to the Committee. The evaluation by IUCN World Heritage Outlook of heritage sites revealed that although the Chitwan National Park authorities were successful in effective conservation practices, threats such as pollution, mass tourism, invasive and alien species and new infrastructure inside, adjacent to or outside the national park still pose a great threat to the World Heritage Value of the park and the site still remains vulnerable. The rising populations of rhinos and tigers show that the World Heritage Values are being maintained. But there is no management whatsoever of the aquatic habitats in the park. The management and protection regime has shown increasing benefits, but still Chitwan National Park is facing many challenges. The authorities are doing their best to maintain the effective regime and management even though their main concerns are the megafauna (large animals such as the rhino and tiger). More attention needs to be given to aquatic animals such as otters and the fishing cat.

The overall picture of Chitwan National Park reveals that the inscription of the national park in the World Heritage List has aided in the protection and conservation of the fauna and flora of the park. The inscription has helped the national park to take effective measures for the conservation, policy and law making involved in protecting the OUV of the World Heritage Site. It has also helped international cooperation, scientific research and monitoring.